Jews rock! You know it even if you don’t know it. Among the contributions of Jewish thinkers, artists and doers to every area of human endeavor is the vastly underappreciated role of Jews in rock & roll, on both sides of the talent-management divide—from punk icons like Joey Ramone and visionary songwriters like Bob Dylan, to managers like the Beatles’ Brian Epstein and label honchos like the Chess brothers and Rick Rubin. Or think of UK soul diva Amy Winehouse, or ebullient sister act HAIM. So crank up our new Freegal playlist and rock out with the explosive sounds of the chosen people this Jewish American Heritage Month!

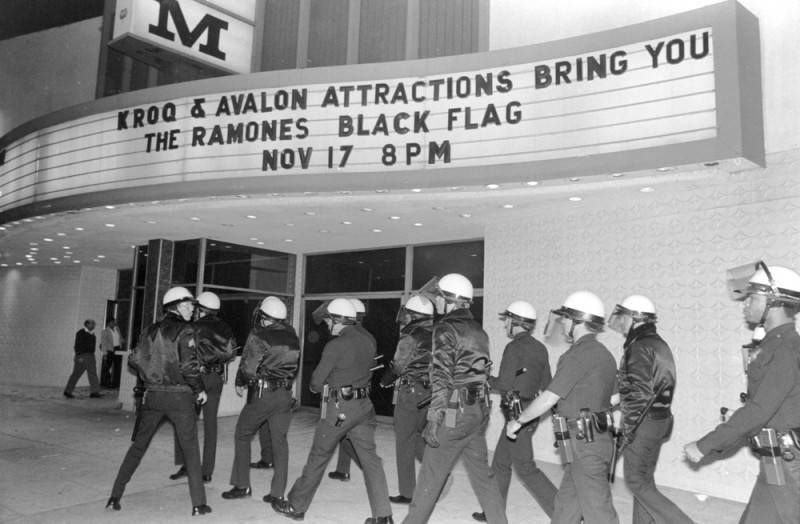

Of course Jewish composition and songwriting run all through the 20th Century, going way back to Irving Berlin (Israel Baline, who wrote “God Bless America” and “White Christmas”). In the mid-century, Manhattan’s Brill Building became the locus of pop hitmaking, where clock-punching aspirants in tiny offices with upright pianos cranked out 3-minute hits for teen heartthrobs, doo-woppers and girl groups. Some of those predominantly Jewish songwriting duos included Burt Bacharach and Hal David (“Walk on By”, “I Say a Little Prayer”), Gerry Goffin and Carole King (“Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow”, “The Loco-Motion”), Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry (“Be My Baby”, “Da Doo Ron Ron”, “Leader of the Pack”), Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller (“On Broadway”, “Stand By Me”), Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman (“A Teenager in Love”, “Save the Last Dance for Me”), and Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil (“You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feeling”). Lesley Gore (Goldstein) hit it big with “It’s My Party” while still a junior in high school, and followed it up with a string of subtly feminist hits. Phil Spector started out in this scene but quickly forged his own path in songwriting, labels, and talent management that produced the towering girl-group sounds of the Crystals and the Ronettes and the Beatles’ final sessions, Let It Be, all featuring his massive Wall of Sound arrangements.

Many future stars got their start in Manhattan’s hit factory diaspora before striking out on their own in the 1960s, whether continuing in the mainstream pop vein like Neil Diamond, Barbra Streisand and Bette Midler, or changing gears to sing their own more personal, poetic oeuvre, like Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel, Donald Fagen and Walter Becker (later Steely Dan), and even Lou Reed (whose father changed his name from Rabinowitz). Iconoclasts like these wound up rebelling against the assembly-line pop of the 50s to create more thoughtful, critical, dynamic rock forms as the 60s cut loose into the 70s—though others, like Randy Newman and Billy Joel played it a little more traditionally. And of course America’s most legendary Jewish rocker, singer-songwriter Bob Dylan (born Robert Zimmerman), developed his homespun style in direct opposition to the Brill Building mode, taking the rustic Americana of Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger and supercharging it with the boundless lyricism of writers like Kerouac, Rimbaud, and Whitman.

Jewish hippies were an important part of the late 60s counterculture, from Abbie Hoffman to Michael Lang who organized Woodstock (thanks to Jewish farmer Max Yasgur providing the festival grounds), where Country Joe led the crowd in his satirical Vietnam War protest anthem “Fish Cheer / Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-To-Die Rag”. Impresario Bill Graham (born Wulf Grajonca), no hippie himself, emigrated from Europe to escape the Nazis in 1939 and went on to run music promotion companies like the Family Dog and venues like the Fillmore and Winterland that made bands like the Grateful Dead and the Jefferson Airplane famous. Randy California (as Jimi Hendrix nicknamed young Randy Wolfe after a jam session) founded the mystical and still-underrated L.A. combo Spirit. Orthodox Jew Norman Greenbaum capped the hippie era in 1969 with his electric crypto-Christian boogie “Spirit in the Sky”, which he claimed was inspired not by Jesus but rather by his love of old Western movies where gunfighters faced their fate and died with their boots on.

Across the pond, brilliant Jewish rockers blasted off in a variety of idioms. Peter Green (Greenbaum) founded Fleetwood Mac, inspired by Chicago electric blues but developing their own soulful sound, known for Green’s timeless “Albatross” and “Black Magic Woman” long before their evolution into 70s arena-rockers. Three of the four of the members of pop subversives 10CC were Jewish, a band better-known in the UK but still scoring a few well-crafted stateside hits like “I’m Not In Love” and “The Things We Do For Love”. Before joining 10CC, Graham Gouldman penned fiery singles for British Invasion bands, like the Hollies’ “Bus Stop” and the Yardbirds’ “For Your Love” and “Heart Full of Soul”. The Shulman brothers played complex prog-rock as Gentle Giant, and Thijs Van Leer founded Dutch progsters Focus.

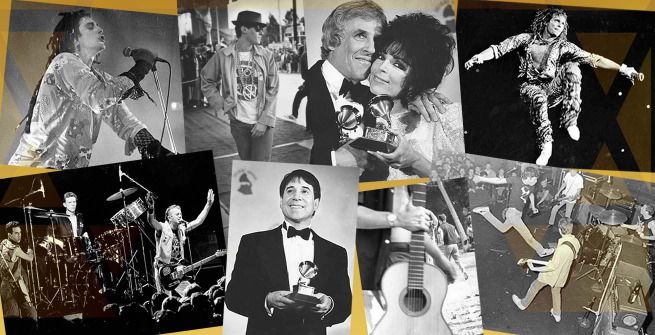

Cultural stereotypes make it easy for most people to see moody, bookish folkies like Leonard Cohen and Phil Ochs as Jewish, but not everybody realizes there are plenty of Jewish hard rockers out there too. Including many full-on guitar-slinging, eardrum-blasting, whiskey-guzzling, parent-terrorizing metal maniacs! Marc Bolan (Marc Feld) got the party started with the irresistible glam of T. Rex on stompers like “Get It On (Bang a Gong)” and “20th Century Boy”, and Mountain’s Leslie West threw down the heaviosity of “Mississippi Queen”. Kiss can seem a little calculating with their simplistic riffs and action figure costumes, but Paul Stanley (Stanley Elsen) and Gene Simmons (Chaim Witz) steadfastly busted out the Judaic rock power on a decade-long string of hits, electrifying stadiums of thrill-seekers with their incendiary theatrics. Geddy Lee fronted inventive Canadian rockers Rush on their space-age odyssey. Pasadena’s own David Lee Roth took the chart aspirations of Kiss to a high-kicking new level as the singer of Van Halen, always keeping his beloved Tin Pan Alley shuffle in the back pocket. (When he and the band parted ways, fellow son of Abraham Sammy Hagar took over.) The hilariously growling Dee Snider scandalized squares with Twisted Sister’s tongue-in-cheek songs like “We’re Not Gonna Take It”—and hey, they made a pretty good Christmas album too. Scott Ian (Rosenfeld) and Dave Mustaine revved up the tempo with the bombastic thrash metal of Anthrax and Megadeth in the ‘80s. Steven Adler’s songwriting and Saul “Slash” Hudson’s guitar solos helped power Guns ‘N Roses, and Perry Farrell (Peretz Bernstein) fused grunge and metal in a distinctively L.A. way with his band Jane’s Addiction.

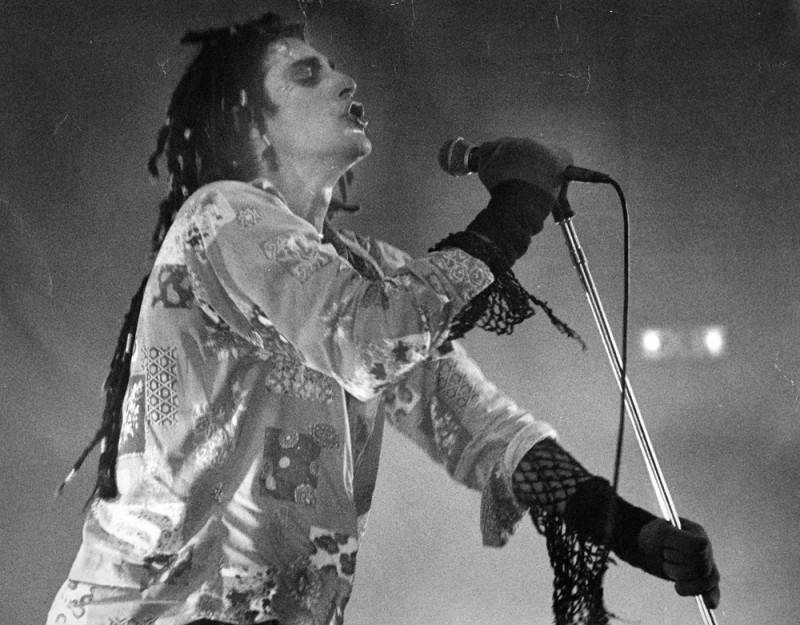

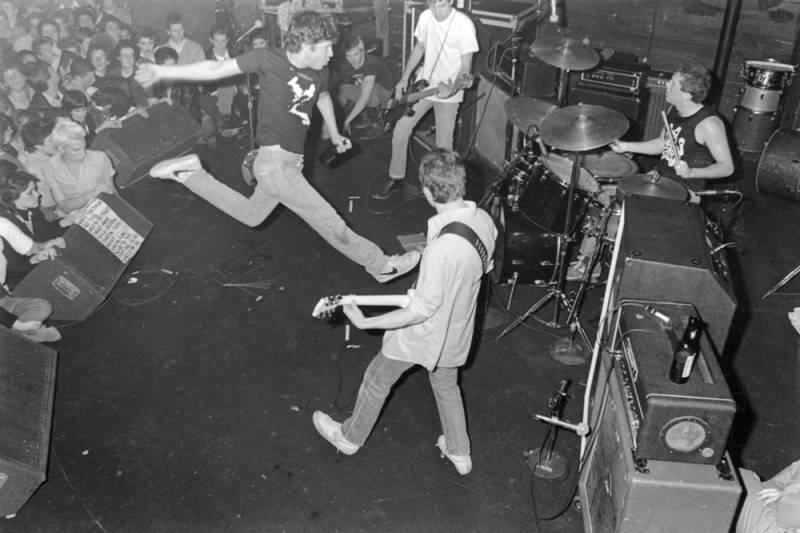

But perhaps the strongest Jewish influence can be found in punk rock, a natural fit for those who appreciate its outsider stance and biting social critique, despite its occasionally fascist overtones. As L.A. punk photographer Jenny Lens puts it on her website, Jewish Punks 1974-80:

“Jews are the original punks. Scrappy outcasts, relying on our inner lives, imaginations, music, art, and intellect to survive slavery and various attempts at eliminating us (the Final Solution aka the Holocaust). Most of us were not traditionally religious—many were raised on the fringes of Judaism, which can be as restrictive as Catholicism, but our heritage influenced us to take risks. When people have tried to kill you for thousands of years, what have we got to lose?”

Lou Reed was a New York punk forefather, muttering cynical tales of junkies and deviants over the Velvet Underground’s raw, seething churn. He inspired the likes of Suicide, the duo of downtown minimal-synth provocateurs Martin Rev and Alan Vega (born Alan Bermowitz), who yelped belligerently over a relentless electronic buzz, and Boston naif Jonathan Richman, wailer of jittery anthems like “Roadrunner” with the Modern Lovers. The New York Dolls belted out gloriously obnoxious trash in lipstick and feather boas, with Sylvain Sylvain (Mizrahi) on guitar. One of the most ferociously funny and badass bands of all time, the leather-jacketed Ramones took the teen melodrama of the Ronettes and the Shangri-Las and cranked it up to a four-count cretin hop plastered with hilariously New York-y lyrics. Two founding Ramones were Jewish, singer Joey (Jeffrey Hyman) and drummer Tommy (Erdelyi). Blondie guitarist and songwriter Chris Stein took a similarly nostalgic tack with their effervescent new wave pop. Lenny Kaye (Kusikoff) wrote songs with Patti Smith, and just as crucially, curated the original Nuggets compilation that taught aspiring punks about tough ‘60s garage rock 45s. Tom Verlaine, Richard Lloyd and Richard Hell (Myers) founded the avant-punk Neon Boys, later splitting off into Television and Richard Hell & the Voidoids. The fast n’ loud Dictators satirized their own Jewishness in a combative way that tended to subvert their success, but that their fans still find pretty funny. Many of these bands got their start on Seymour Stein’s new wave label, Sire Records, and played live on Hilly Kristel’s CBGB stage.

Beyond New York, the Ramones’ concerts in England in 1976 helped kick off the punk revolution there, with kids in attendance who would go on to infamy in bands like the Damned and the Sex Pistols. Joe Strummer and Mick Jones, the frontmen of one of the greatest UK punk bands, The Clash, were both of Jewish descent, as was their manager, Bernie Rhodes, who anecdotally had little patience for the hippie-baiting swastika fashion accessories sported by many ignorant young punks, and would threaten to cancel Clash concerts if these were not removed. The Sex Pistols’ manager Malcolm McLaren, always up for inflammatory grandstanding to promote his band, was less circumspect about fascist punk fashion, despite his Jewish roots. Keith Levene was an early Sex Pistol and later wound up in the arguably more interesting Public Image Ltd.. Geoff Travis started one of England’s longest-lived and most influential record labels, Rough Trade, its communal ethos inspired by his time spent living on a kibbutz. Music journalist Vivien Goldman sang on some influential records, including an EP produced by John Lydon and Adrian Sherwood as well with the Flying Lizards. She is now a documentarian and teaches cultural history at NYU and Rutgers.

In California, the Circle Jerks’ classic lineup featured several Jewish members, including frontman Keith Morris, guitarist Greg Hetson, bassist Zander Schloss and drummer Lucky Lehrer. Dead Kennedys singer Jello Biafra (Eric Boucher) recently learned he has some Jewish ancestry, an apposite discovery for the man who belted out “Nazi Punks F— Off!” Milo Aukerman of the Descendents is Jewish, as are Stan Lee of the Dickies, Steve Wynn of the Dream Syndicate, Nicky Beat from the Weirdos and Fat Mike of NOFX. Many first-generation California punk fans fondly recall Mark Hecht’s band Jews From the Valley, who celebrated their heritage with a shot of punk humor in their screaming rendition of “Hava Nagila”.

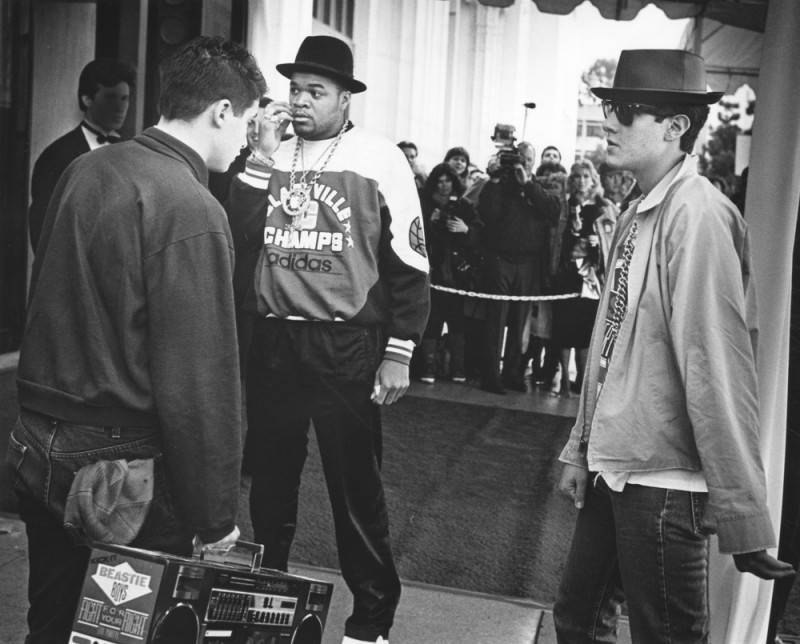

Jewish musicians in recent decades have found both mainstream success and underground notoriety. At the same time that three Jewish punks-turned-rappers, the Beastie Boys, were hitting it big as one of the world’s most successful hip-hop groups, downtown avant-garde saxophonist and composer John Zorn was mining musical netherworlds, recording everything from flailing experimental improvisation to surf, drone, and metal. Working with his Masada ensemble and Tzadik label often explores his Jewish heritage, and especially so his Radical Jewish Culture series. In a similar way, Jewish pop stars like Adam Levine, Pink), HAIM, and Jack Antonoff now top the charts, while weirder rockers explore more far-out territory—like the Melvins’ Buzz Osborne, who has been assaulting underground rock fans’ eardrums for decades with his band’s snarling sludge, and stoner rock underlord Gene Ween (Aaron Freeman), whose huge fanbase worships the Boognish and other meshuggeneh elements of Ween lore.

Somewhere in between are artists who appeal to both the mainstream and the underground—like Amy Winehouse, who brilliantly updated the boss diva sound of Etta James before her untimely death in 2011, her producer Mark Ronson, who crafted the sound of Sharon Jones and Bruno Mars, and the great Sleater-Kinney, one of the most righteous indie bands to come out of the Northwest riot grrrl scene, featuring Carrie Brownstein and Janet Weiss.

As Ben Sidran sums it up in There Was a Fire: Jews, Music and the American Dream:

“Jewish popular music in America is a kind of spiritual music, and it arises, both directly and indirectly, from many of the same causes that gave voice to the songs of King David more than three thousand years ago. In American popular music, you may be calling the name of the girl next door, but more often than not, you are singing about the life of the soul… Hope, transformation, change, in a three-minute version, with an elegant melody, a couple of hooks, and a good beat, it’s the American popular song.”

Author's note—Jewish heritage often involves complexities and degrees, and does not necessarily imply belief or observance: the attributions in this post are either self-professed or claimed by reputable sources. For a much longer and more in-depth exploration of this topic, check out Sidran’s book, or Guy Oseary’s Jews Who Rock.