Overview | Early History, Design and Construction of the Goodhue Building | Explanation of Themes and Inscriptions | Sculpture for the Goodhue Building | Painted Decoration in the Goodhue Building | Tom Bradley Wing: History and Design | Public Art Projects

All of the sculpture on the exterior and interior of the Goodhue Building was created by Lee Lawrie, a prominent member of the last generation of American sculptors to practice the traditional art form of architectural sculpture. German by birth, Lawrie immigrated to the United States with his widowed mother and grew up in Chicago. Apprenticed as a teenager to sculptor Henry Park, he became part of the team of artisans who produced the elaborate program of Beaux-Arts style statuary for the Worlds Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893.

Lawrie first met Goodhue in the mid-1890s when he (Lawrie) was about age 20. Working first with Cram and Goodhue, then with Goodhue on his own, Lawrie produced sculpture for a variety of major architectural commissions over the next two decades. In the process, he and Goodhue became esteemed friends as well as close colleagues. When in 1921 the American Institute of Architects awarded Goodhue a medal of merit, he insisted on having it re-engraved to share credit with Lawrie.

The two collaborators’ breakthrough opportunity came when Goodhue won the commission to design a state capitol building for Nebraska and insisted that Lawrie be hired to model all of the sculpture. Together they worked to fuse sculpture and architecture into a simplified, completely integrated design. Here is Lawrie’s description of their achievement from a memorial tribute to Goodhue:

In 1922 after a great many preliminary sketches for the work of the Nebraska Capitol, Mr. Goodhue and I arrived at a new kind of architectural sculpture that is essentially a part of the building rather than something ornate or applied...

Sculpture, here, is not sculpture, but a branch grafted on to the architectural trunk. Forms that portray animate life emerge from blocks of stone and terminate in historic expression.

Bertram Goodhue and Lee Lawrie: Nebraska State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska. Photograph courtesy of Sharon Hartmann, 1922-1932

Lawrie was again Goodhue’s choice for the library commission. On the same day, March 13, 1924, that he received Hartley Burr Alexander’s initial proposal for a library iconography, Goodhue wrote an enthusiastic note to the sculptor, “This morning I received a magnificent scheme for the inscriptions and sculptural subjects. I am anxious to show this to you, so won’t you telephone that you will come down...” (Goodhue’s office was on 47th St and Lawrie’s studio about 50 blocks north.) Clearly Goodhue was looking forward to debating with the sculptor ways of translating Alexander’s new iconographic scheme into sculpted form.

Goodhue’s sudden death some five weeks later meant that, instead of tackling a new project as a team, his former colleagues would face the sad task of finishing his remaining commissions without his leadership. Probably none of Goodhue’s associates was more devastated at his passing than Lee Lawrie. Here from a letter, he wrote to Hartley Burr Alexander on April 29, 1924: “It will be difficult for me to go on without him. This is the twenty-ninth year that I have worked with him. I am the only one who really needs his help, for while my part is sculpture, it is really /nothing more than/ his architecture in plastic form.”

Goodhue’s absence put Lawrie in a difficult position vis-a-vis the library board. All Los Angeles city contracts of any size were subject to competitive bidding. This was common practice but on previous commissions, Goodhue had been available to champion Lawrie and serve as a buffer between sculptor and clients. In the end, an anxious and frustrated Lawrie was forced to go through two rounds of bids before he was selected on January 14 of 1925. Whether any of the decision-makers understood how crucial Lawrie’s sculpture would be to realizing the building as conceived by Goodhue, something obvious with hindsight, they finally were willing to honor what was clearly the architect’s intention.

Central Library's Sculpture

Note. This section discusses the style of Lawrie’s library sculptures. For information about the subject matter, see the section on Themes and Inscriptions.

The Central Library is one of the last great US civic buildings to be decorated with an ambitious sculptural program. For the library, as with the Nebraska capitol, Lawrie and Goodhue were proposing a compromise modernism, one that sought to transform the Beaux-Arts style so closely associated with the City Beautiful movement into something simpler and more direct. Complete integration of sculpture with components of architectural design was their goal. As Lawrie later wrote, “One might describe the building without the sculpture, but the sculpture cannot be conceived at all without the building.” Their solution was widely admired but the tradition of combining sculpture and architecture, which reaches back into antiquity, would soon expire as modern building practices evolved towards industrial materials and functional forms stripped of ornament.

Although working without Goodhue, Lawrie had the advantage of the architect’s very detailed plans. On projects where the two collaborated, Goodhue would typically make decisions regarding the placement, scale and shape of each decorative element for a building’s design and at that point, hand the project over to Lawrie. The two had worked so closely for so many years that the architect felt no need to supervise his sculptor’s creative process. According to Lawrie, Goodhue would simply point to a space in an architectural drawing and say, “You know what to do here”.

Allegorical representation of Shakespeare on the library tower, 1926

The tower and the south (Hope St) facade most thoroughly exemplify Lawrie’s characterization of his art as “a branch grafted on to the architectural trunk.” Eight “seers of light” were situated on inner angles of the parapet that frame each corner of the pyramid tower. Although documents refer to these busts as representations, they actually appear to be allegorical figures holding attributes that symbolize the writers and thinkers whose names are inscribed on the tower parapet. Modeled in relatively low relief and since seen from distance, they blend with the building’s surface.

The Hope Street facade presents true portraits of famous thinkers linked to categories of knowledge. Six elegantly articulated pilasters run between the high windows of the main reading room and overlap a simple entablature, each culminating in the bust of a great thinker who embodies a category of knowledge. One’s eye travels up from subtle shallow carved drapery into deeply carved, crisply detailed individual heads, each with distinctive features that imply portraiture. Lawrie employed simple, faceted shapes that read easily from a distance and convey an air of dignity and universality.

Busts of Socrates, the Emperor Justinian and Leonardo da Vinci

on the Hope Street facade

Bust of Leonardo da Vinci

The west (Flower Street) facade seems to have been planned by Goodhue as a dynamic contrast to Hope Street. Where Hope Street’s entire facade is segmented and rhythmically articulated by sculpture crowned pilasters, Flower Street concentrates virtually all of the sculpture on the upper surface of a pylon-like portal projecting from the middle of the facade. The whole is characterized by an almost muscular tension.

Sculpture on portico of Flower Street facade

Sculpture of Hesper

Relief of sunrise below sculpture of Phosphor

Directly beneath the quote from Lucretius is a tightly framed horizontal relief of riders passing a torch left to right. It links the two massive three quarter length figures of Phosphor and Hesper who stand encased in deep niches. Each clasps a scroll that in effect is a flat plane overlapping the deeply three dimensional carving of their muscled torsos. It is as if the wall itself were forcing the embedded figures back behind its surface.

The play of interlocked surfaces has a pronounced Art Deco quality. With Phosphor and Hesper one can see evidence of the impulse that would come to full flower in Lawrie’s later work at Rockefeller Center. Everything appears modernized, in other words, flattened and self-consciously stylized. Decorative motifs like the rising and setting suns beneath the figures’ feet are executed in crisp, shallow relief and accompanying ocean waves abstracted to a classic volute pattern. In an adventurous touch, Lawrie set up a deliberate dissonance between the classic Roman lettering used in the quote from Lucretius and the lettering of the scrolls. The latter appears to be Plaza, a fashionable Deco typeface widely used in commercial signage during the 1920s. (Lawrie used the same lettering on a memorial plaque for Everett Perry located in the rotunda.)

Sculptures of the Philosopher and the Poet on Fifth Street (north) facade

The north (Fifth Street) entrance is almost flush with the sidewalk and quite shallow but with the subtle detail that was such a strength of Goodhue’s designs. Like the Flower Street entrance, its shape recalls ancient mortuary temple entrances, an effect seconded by the attached sculptures of the Philosopher and the Poet whose cubic forms merge with the limestone surface. Framed by the portal’s edges, they resemble rigidly posed Egyptian funerary sculptures and, flanking the seal of Los Angeles, endow it with an air of timeless monumentality.

Tunnel and Garden

Relief sculpture over tunnel entrance from Hope Street

In addition to the major facades, Lawrie created two low reliefs for other areas of the building and grounds. One of the library’s entrances was a pedestrian tunnel running from sidewalk level at the Hope Street cul-de-sac up to an elevator vestibule.

For the lintel Lawrie carved an elegant low relief, somewhat medieval in feel, that centers on a printing press, flanked by profile depictions of important figures in the history of printmaking. The last panel on the right depicts Bertram Goodhue, who in addition to his many other talents was a skilled designer of typefaces.

Lawrie modeled another subtly detailed relief for a low basin that served as a terminus point for the West Garden’s water feature. Three rectangular pools flanked by low steps and cypress trees stretched from the west entrance to the street. At the end of each pool, a runnel allowed a trickle of water to fall into a semi-circular basin below. The largest lowest pool was sculpted in bronze by Lawrie who together with Hartley Burr Alexander devised a theme, The Well of the Scribes. Lawrie’s design centered on a winged horse symbolizing inspiration and on each side a procession of elegantly detailed single figures in profile representing scribes from various early cultures. The basin was removed when the West Garden was paved over in 1969, and for 50 years its whereabouts was unknown. In 2019, Alta magazine published a story about its disappearance. An antique dealer in Bisbee, AZ read the story and recognized a piece of the Well he had purchased 10 years earlier. The section of the Well was returned to Central Library, and the search for the remainder of the Well continues.

Well of the Scribes, previously located at foot of the West Garden.

Interior

The Triumph of Civilization

Lawrie executed three sculptures for the library interior, all part of an ensemble located at the top of the North Staircase. Actually devised by Bertram Goodhue, the subjects relate to the origin of culture in ancient civilizations. Two sphinxes frame the top of the staircase, and a standing figure titled Civilization is placed in a niche opposite the stairs.

Lawrie had an intriguing sometime tendency to work within style idioms related to his sculpture’s subject matter. Probably suggested by a cult statue of Pallas Athena, Civilization is rendered in the stiffly archaic style of 6th century BCE Greek statuary, while the svelte elegance of the sphinxes seems to hover between New Kingdom Egypt and Art Deco. For these artworks meant to be seen close up in artificial light, Lawrie makes use of color: black marble and bronze for the sphinxes and two colors of marble, bronze and copper for Civilization. The workmanship on all three sculptures is exquisite and demonstrates why, when given the opportunity, Lawrie generally relied on a team of skilled craftsmen assembled by sculpture fabricator Edward Ardolino.

A Sphinx

Metalwork

In addition to the sculpture, Lawrie modeled much of the important metalwork which decorated the library exterior and interior. This included the paneled bronze doors which stood at each major entrance, gates used to close off parts of the interior on Sundays, lighting fixtures and the chandelier which hangs from the domed ceiling in the rotunda.

The chandelier, nine feet in diameter, is one of the Goodhue Building’s spectacular decorative features. Suspended on chains decorated with stars and crescent moon, it centers on a glass globe surrounded by signs of the zodiac which are framed by forty-eight lightbulbs.

The Zodiac Chandelier. Photograph courtesy of Mary Valentine

Lamp stanchions reproduced from a design by Lee Lawrie. Photograph courtesy of Mary Valentine

Lawrie’s elegant light fixture designs enrich the austere concrete-walled interior spaces. His table lamps mounted on tall stanchions added a graceful note to the long reading tables of the history department, mitigating the room’s somewhat cavernous quality. Placed on pedestals in that room which was renovated as the Children’s Department, precise reproductions function equally well today.

Sculpture for the East Wing

The remainder of Lawrie’s library sculpture was located on the East Wing, demolished during the 1980s to provide room for the major addition which now houses most of the library’s collection. That artwork was preserved and has been installed in the wing containing the Taper Auditorium and its adjoining patio. Every effort was made to recreate the original context of the doorways and patio where each sculpture was originally installed--the patio is virtually an exact replica of the original in the old Children’s Department.

Surround for entrance to former Children’s Department.

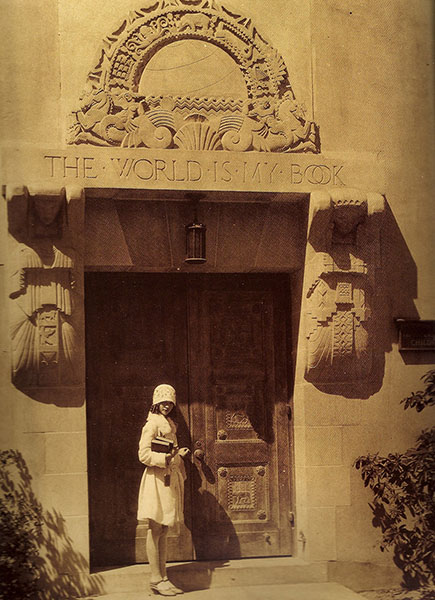

Photograph from the late 1920s

For the Children’s Department entrance and patio, Lawrie contrived a body of sculpture quite different in spirit from the rest of his work for Goodhue’s library. Inventive and playful, it suggests the heady joy of a child’s imagination connecting to the world of books. The lower level entrance was embellished with a magnificent surround. Caryatids support a lintel carved to read “The World is my Book” and above it is a sort of tympanum containing a variety of references to mythology and ocean voyages. Typical of Lawrie’s design sense, the intricately carved detail on both the caryatids and the tympanum is emphasized by the plain oblong lintel with its sober lettering style.

Lotus Fountain located in the Children’s Patio

The East Wing was built around a courtyard accessed through the Children’s Department. It centered (as does its recreation today) on a lotus shaped marble fountain incised with low reliefs depicting royal mothers instructing their sons. The style of the carved reliefs is dense and delicate, resembling an illuminated manuscript or a drawing by Aubrey Beardsley.

But the real treat of the courtyard are the carved panels of scenes from classics of children’s literature. Conceived and executed with great skill and wit, they mimic black and white children’s book illustrations. The panels are deeply chiseled, yet have flat surfaces so they present an elegant combination of two and three dimensional effects, and the abstracted, caricature-like shapes embody a surprising amount of movement. When viewed in sequence they carry the eye around their courtyard space and lighten its somewhat box-like quality. Seldom would a sculptor have the opportunity to work in such a playful, sophisticated mood for a major public building commission.

Relief panels depicting Alice and the Red Queen, the Cow Jumps Over the Moon and Robin Hood