Welcome to Summer Reading at the Los Angeles Public Library! This year our theme is My L.A., and we hope you will join us in reading all about our fair city! But first, let’s turn back the clock for a look at the hidden history of summer reading and the beach read book…

"These paper covered romances… the heroine an unprincipled flirt… chapters in the book that you would not read to your children at the rate of a hundred dollars a line?" thundered the Reverend T. De Witt Talmadge in 1876. "I readily believe that there is more pestiferous trash read among the intelligent classes in July and August than in all the other ten months of the year." He was of course fulminating against the new craze for light summer reading, especially among young women whose impressionable minds he yearned to deliver from temptation. Nowadays when the May Gray burns away, we hardly bat an eye at the inevitable superbloom of "Best Beach Books" listicles and bookstore displays piled high with poolside pulps, slathered in tangy neon or Tuscan pastels. In Books For Idle Hours: Nineteenth-Century Publishing and the Rise of Summer Reading, Donna Harrington-Lueker brilliantly unearths the beginnings of the modern phenomenon of the beach read, tracing it to canny Victorian publishers seeking to capitalize on the burgeoning trend of summer vacation travel. They turned a traditionally slow time of year for book sales into a season of sizzling sun-drenched bestsellers, with plots often set at resorts and destinations.

And it wasn’t just the publishers. Harrrington-Lueker shows that even writers as staid and upright as Quaker abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier were keen to get in on the action. After his poetry collection Snowbound was a hit in 1866, his publisher James T. Fields urged him to get another book on the shelves quickly. He complied in early 1867 with The Tent on the Beach, a poetic recounting of his trip to a coastal town some years earlier, where he basked in the sun and enjoyed the restorative graces of nature. The book "ought to be out by the first of June," Whittier urged Fields. "It is a sea side idyll and it is wanted then, if ever." Et tu, Greenleaf? The Tent on the Beach turned out to be a huge summer bestseller and set off a fad for beach camping at that same town.

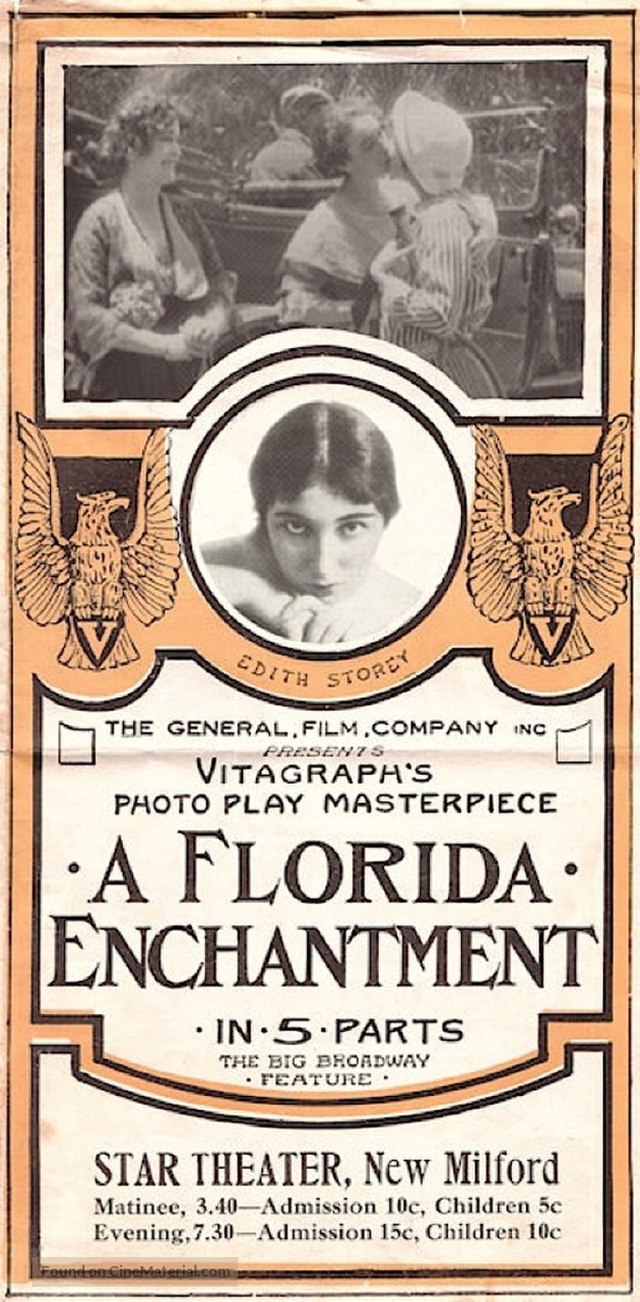

Harrington-Lueker follows this with a fascinating cavalcade of long out-of-print Victorian summer romances, awash in twisty plots featuring raffish beaus and dizzy heiresses dancing, prancing, and partner-swapping at resorts like Saratoga and Cape May. My favorite of her synopses is of an 1892 book called A Florida Enchantment, in which the heroine "eats a mysterious seed that transforms her into a man, giving the young woman the opportunity to exact revenge on her faithless lover and providing readers with the chance to explore, quite explicitly, the nature of same-sex and opposite-sex desire."

But it was not always so. Prior to 1850, summer reading was usually presented as an act of "good taste, deliberation, and gentility." One was encouraged to "walk slow, talk slow, think slow" in summer—eschew the tumult of political opinion columns and soothe your intellect with the serenity of the classics. It was also explicitly positioned as an activity for (elite, white) men, whose example women might do well to emulate.

Then during the second half of the nineteenth century, America’s population tripled, and its cities boomed. The country blasted off from an agrarian way of life into the industrialization that produced a middle class, with white-collar jobs offering stable salaries and vacation time off. Along with the massive urbanization came the crowds, the noise, and the hubbub, and especially in summer, the smells and the heat. All this made escaping the city for summer travel a desirable option for a vast new set of people beyond the upper crust—including, as Harrington-Lueker shows, affluent African Americans, who vacationed at many of the same destinations as whites or developed their own when barred by segregation. Further democratizing the leisure industry was the proliferation of steamboat lines and railways that could quickly take one to the coast or countryside. Sleepy seaside towns and resort spas responded to the influx of tourists by building piers, hotels, esplanades, and attractions. Newspapers and magazines celebrated it all in print, teaching Americans how to do summer.

Book publishers were no enemies of the dollar. One of their chief concerns in the decades before the passage of the International Copyright Act in 1891 was a wave of lurid pulp dime novels and pirated European novels which were popular with the increasingly literate American readership, stirring up a backlash from the pulpit against sinful sensationalism defiling impressionable readers’ minds. Publishers seeking to sell a nation of vacationers on a positive view of summer reading took pains to introduce a new discourse that framed it "not as a disreputable indulgence but as a respite from the increasing pressures and complexities of Victorian life," along with imprints that explicitly referenced summer leisure, like Appleton’s Town and Country Library and Holt’s Leisure Hour Series. Critics and reviewers helped out, proffering the stance that "rather than being a danger to a person's immortal soul, summer novels were simply appropriate for the holiday frame of mind… a way to fill the vacant hours, protect against the boredom (ennui) of wet days, and provide agreeable companions when the ladies were not inclined for company." Distribution strategies diversified, ensuring that these books were easily snapped up at coastal gift shops and newsstands.

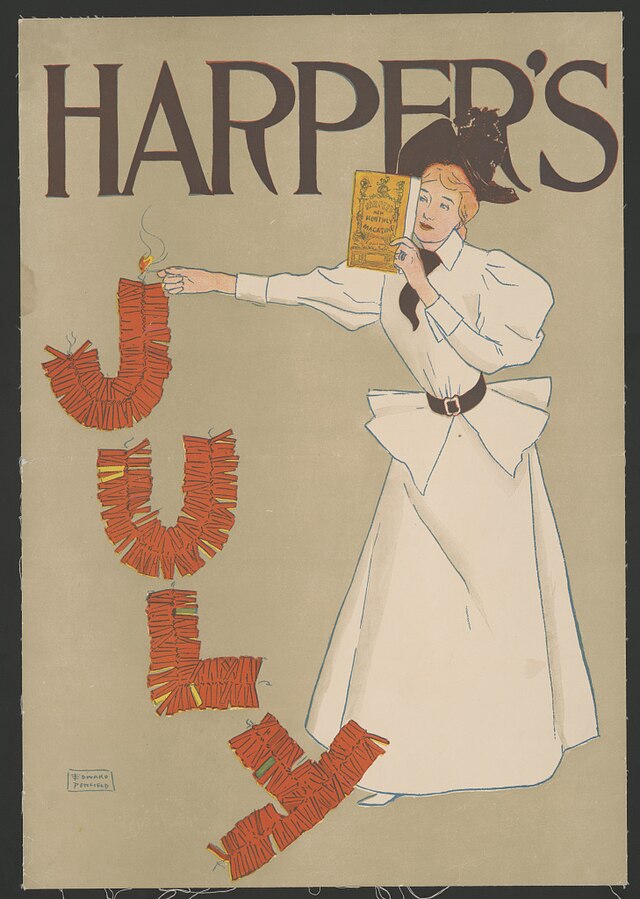

The new positioning of summer reading was definitively feminine; the advertising imagery all trended towards ladies in hammocks or sitting in the shade, happily immersed in a page-turner. A typical effusion from Harper’s in 1889:

"As certainly as the birds appear, comes the crop of summer novels, fluttering down upon the stalls, in procession through the railway trains, littering the drawing-room tables, in light paper covers, ornamental, attractive in colors and fanciful designs, as welcome and grateful as the girls in muslin." These middlebrow summer books were designed for flexibility and disposability. "They have a cool and summery look," enthused American Bookmaker in 1887, and "may be readily stowed away in one’s pocket or thrust into any unfilled corner of a traveling bag. They adapt themselves to every conceivable reading attitude, from the bolt upright to the recumbent position assumed on a sofa or lounge, or in steamer-chair, hammock or bed, or stretched out on greensward or sandy beach."

Lightly clad, like tourists themselves, the books were a metaphor for holiday release. Harrington-Lueker weaves countless examples of subtle and not-so-subtle marketing into a clear picture of a publishing industry determined to drum up a blockbuster season. Ultimately, the rise of summer reading generated its own reader community—not only vacationers themselves, but even those stuck at home could enjoy the escapism of a frothy summer romance set at an Atlantic City resort.

The Victorian-era marketing of summer reading revealed by Harrington-Lueker marks an intersection of two broader ongoing trends: the development of paperback publishing, and the rise of the romance novel to become the dominant genre in book sales.

Paperbacks were well established in France and Germany in the 19th century, especially with prestige imprint Tauchnitz Editions. But it was not until the 1930s that the mass-market paperback, sold not only at bookstores but also drugstores, bus stations, and chain stores like Woolworths, really took off in England and America. As Kenneth C. Davis recounts in Two-Bit Culture: The Paperbacking of America, there were only a few thousand bookstores in America in the early 20th century, mostly clustered in big cities, and hardcover books were very expensive. In 1935 British publisher Allen Lane launched Penguin Books with ten carefully chosen titles. Robert de Graff followed suit in America with Pocket Books in 1939, setting the standard size of 4.25 inches by 6.5 to fit in wire spinner display racks. Both were wildly successful. They epitomized the high-low divide in paperback content, with Penguin opting for more literary and edifying titles and Pocket satisfying popular appetites with westerns and adventure books. The original Penguin covers were elegantly text-only, while Pocket Books, soon followed by Avon, Dell, Bantam, and Signet, featured eye-catching cover illustrations, often with titillating hints of sex and violence, whether relevant to the texts within or not.

The best-selling sector of paperbacks would soon become romance novels, a genre unique for being mostly written and read by women (some 10-15% of the contemporary readership is estimated to be male). In the 1950s, Canadian imprint Harlequin bought out British romance publisher Mills & Boon and quickly grew to market dominance, selling their books in supermarkets and through direct marketing. Oddly, Harlequin published only UK authors, even in America, dumping their partnership with Simon & Schuster in 1976 and thus setting off the ‘romance wars’ when Simon & Schuster created the imprint Silhouette to compete. Harlequin also had to start adding more steamy scenes beyond their usual kissing-only policy after Kathleen Woodiwiss’ explicitly erotic The Flame and the Flower became a huge hit for Avon in 1972, kicking off the craze for ‘bodice-rippers.’ By 1992 Harlequin was back on top, with an 85% market share. Over half of their readers were purchasing an unbelievable 30 titles a month, according to Forbes. Romance novels accounted for 45% of all mass-market paperbacks sold in 1991, and in 2008 generated sales of over a billion dollars, with some 7,000 new titles published that year alone, according to research conducted by the Romance Writers of America.

Pamela Regis provides an astute defense of the genre in her study A Natural History of the Romance Novel. Starting with Samuel Richardson’s best-selling Pamela in 1740, and continuing through Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre and E.M. Forster’s A Room With A View, the romance novel tells the story of a heroine seeking romantic fulfillment, overcoming barriers without and within to achieve betrothal to her beloved by the end, standard elements from ancient Greek myth switched to a female perspective. Male critics have long scoffed at romance novels (without actually reading many of them) for being shallow, boring, sappy, and formulaic, especially for the genre convention that each must end in some variation on Happily Ever After coupling. But there are plenty of formulaic male-oriented genre novels about cowboys, detectives, spies, and spacemen too, and an entire genre should not be dismissed on the basis of its laziest examples. In the 1960s, feminist critics started slamming romance novels for promulgating subservience to the patriarchy and driving women into the bondage of marriage, which as Regis points out, does not credit romance readers with much agency or willpower. Though not always the most progressive of genres, many consider it at least a somewhat feminist genre, empowering women authors and prioritizing female characters. Regis surveys romance novels with enduring merit from Georgette Heyer to Jayne Ann Krentz, talented authors telling the stories of complex, resourceful heroines.

More telling criticism in recent years has accused the romance fiction industry of racism and heteronormativity. Writers of color and queer writers have clearly been sidelined by Big Romance, and for decades most romance novel plots have seemingly unfolded in all-white worlds. Hardly any non-white romance novels were published before 1970, and no mainstream ones until a decade later. Writers like Rubie Saunders, Sandra Kitt, Beverly Jenkins, and others celebrated in Jessica Pryde’s excellent essay collection Black Love Matters: Real Talk on Romance, Being Seen, and Happily Ever Afters have made some inroads, but publishers tend to segregate African American romances onto special-interest imprints, which then get short shrift from retailers. In 2018 the Romance Writers of America suffered a public lambasting when Alyssa Cole’s acclaimed Black historical romance An Extraordinary Union was snubbed in the nominations for the RITA, its highest award. The RWA acknowledged the problem, admitting in a statement that in the previous 18 years only 0.5% of RITA finalists had been Black authors, and none of those had won. Queer romance, including ‘slash’ fiction, has circulated in the underground press and online for years, but apart from a few noteworthy breakthroughs like Gordon Merrick’s best-selling 1970 gay romance The Lord Won’t Mind and Ann Shockley’s influential 1974 interracial lesbian romance Loving Her, has rarely found mainstream acceptance. The Lambda Literary Award for Gay Romance was first introduced in 2007, and a gay romance was first nominated for a RITA in 2015.

Just as romance has kaleidoscoped in recent decades into a dizzying array of subgenres from paranormal romance to NASCAR romance to Amish romance, the publishing landscape has fragmented too, with independent imprints popping up, fans discovering self-published authors online, and Tik Tok influencers taking up the pen. While the RWA and Harlequin (still the likeliest loci for a profitable career in romance) undergo their racial reckoning, many authors, especially younger ones, have simply moved on. Newer ‘rom-com’ romances, featuring colorfully illustrated covers (without any bodice-ripping) and titles often inspired by ‘80s songs, are more racially and gender inclusive. Romance is diversifying more quickly in some areas than others, but it certainly isn’t going away.

‘Beach reads’: these are often romances, but plenty of non-romance books count too. The term first appeared in trade periodicals around 1990 and has become ubiquitous since. What makes a beach read? Ultimately, a beach read is whatever you feel like reading for fun at the beach or by the pool, but calling a book a ‘beach read’ typically implies a few identifiable features, many of them going back to Victorian summer books.

For one thing, lots of beach reads get you in the mood with plots set at the beach, resort, or travel destination. Beach authors know you want this, and they deliver: think of Taylor Jenkins Reid’s Malibu Rising, Jennifer Weiner’s The Summer Place, Terry McMillan’s How Stella Got Her Groove Back, Mary Kay Andrews’ Beach Town, Emma Straub’s The Vacationers, or Rebecca Serle’s One Italian Summer. Or even a tense, a high-stakes thriller that happens to unfold during a Bora Bora honeymoon, like Catherine Steadman’s Something in the Water. Or any of the dozens of books with a getaway theme that appears on the shelves every year right around May. There may be a beach wedding to plan, with complications in the run-up, a reunion of sisters or friends at a summer rental, or a city gal who is stunned to learn that she has just inherited her aunt’s beach house, which is in need of renovation; fortunately, it comes with a hunky but irascible local handyman. Elin Hilderbrand lives on Nantucket and sets her annual beach read on the island’s sandy shores, with an occasional side trip to the Caribbean. Mary Kay Andrews stakes out the southeastern beaches around Savannah and Hilton Head, while Debbie Macomber lays claim to the northwest coasts of Washington and Oregon.

A beach read is also traditionally a book that requires minimal intellectual stress or heavy lifting; quick and easy reading, light and humorous, with no weighty themes or gritty realism or pressing sociopolitical issues. Think Bridget Jones’ Diary, The Devil Wears Prada, Jasmine Guillory or Sophie Kinsella, or James Patterson. Although in recent years, more highbrow books have begun appearing on beach reads recommended lists, like Thomas Pynchon’sInherent Vice or Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch. For a certain kind of reader, a vacation free from the mental stress of work is the perfect time to tackle that serious tome by James Joyce or Isabel Wilkerson that’s been staring you down from the bedside table.

Or at least, you may want to appear to others to be reading something impressive, like the characters on Netflix’s black-comedy vacation series The White Lotus, who post up by the pool ostentatiously gazing into their copies of Nietzsche and Malcolm Gladwell—a phenomenon known as the ‘braggy’ beach read. Which brings us to another aspect of the beach read: while not necessarily performative, we all know it is something we are most likely going to be seen reading, so title selection carries a certain social acknowledgment. For many, it is important to get with the zeitgeist by reading the year’s ‘it’ book—Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, Liane Moriarty’s Big Little Lies, Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven, Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere. This year’s ‘it’ book is still to be determined, but so far Prince Harry’s Spare is looking like a contender.

And don’t forget about horror! Ever since Steven Spielberg turned Peter Benchley’s Jaws, about a great white shark terrorizing beachgoers at Amity Island (a stand-in for Martha’s Vineyard) into the first summer blockbuster movie in 1975, horror novels from Stephen King, V.C. Andrews, and Anne Rice have made their way into beach bags. Grady Hendrix documents the horror boom of the 1970s and ‘80s in his delightful survey Paperbacks From Hell, packed with glorious images of die-cut book covers with embossed foil titles featuring demented clowns, killer rabbits, skeleton doctors and homicidal toys. Though Hendrix surmises that Thomas Harris’ The Silence of the Lambs marked the boom-ending shift in marketing terminology from ‘horror’ to ‘thriller’ in 1988, horror is defiantly back today, with a whole new generation of writers here to chill your spine including Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Stephen Graham Jones and Victor LaValle.

You could also go dystopian with an anti-beach read, like Nevil Shute’s 1957 On the Beach, about a group of survivors of a nuclear war in southern Australia waiting for the inevitable radioactive fallout cloud to come down. Or Camus’ existentialist classic The Stranger, in which the protagonist engages in seedy nihilism in Algeria, ultimately killing an Arab on the beach and ending up in prison. Or something depressing but informative like Sarah Stodola’s The Last Resort: A Chronicle of Paradise, Profit and Peril at the Beach, in which she digs beneath the surface of the world’s most tourist-mobbed beaches to tell their true stories of unsustainable overdevelopment, overuse and environmental destruction.

Media-savvy readers that we are, we know we are being targeted by the beach read industry, but we need those darn things anyway. Emily Henry nails the dilemma in her enjoyably meta 2020 bestseller Beach Read, in which romance novelist January Andrews runs into her old college rival Augustus Everett, now an acclaimed literary fiction writer. Both are struggling with writer’s block, and they challenge each other to spend the summer writing a book in the other’s genre; January will aim for the Great American Novel, and Augustus will have to try to write something light and romantic. Look for the movie version soon… or just read it!

Whatever kind of beach read you choose, happy summer reading!