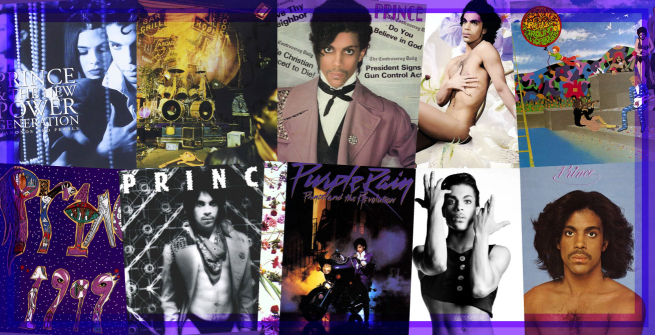

Prince Rogers Nelson was born on June 7, 1958 in Minneapolis. In the 1980s, Prince became one of the greatest pop stars of all time, selling some 150 million albums, recording scores of incomparable hit songs, and inspiring fans worldwide. If you know nothing else about him, you know "Little Red Corvette," "Kiss," "1999," "I Would Die 4 U," and "Purple Rain." (And if you want a deeper dive, head on over to Freegal, the Los Angeles Public Library's streaming music partner, to enjoy my mega playlist of Prince rarities!)

To longtime fans like me, 'greatest' hardly does Prince justice: he was one of the most accomplished, poetic, virtuosic, creative, mystical, tireless, charismatic, and expansive musicians ever to do it. He crossed boundaries effortlessly, delivering shredding guitar solos, poignant balladry, new wave synth, rump-shaking funk, political consciousness, erotic epistemology, spiritual liberation, and endlessly catchy pop tunes. On the other hand, he could also come off as absurdly messianic, sex-obsessed to a fault, grouchy, and humorless. (Occasionally, he was pretty funny.) He rarely granted interviews and was famously coy or rude when he did; all part of his cultivated mystique. Some of his decisions struck people as bizarre, as when he publicly changed his name to an unpronounceable symbol in the early 90s, although once you learned the whole story, it started making sense. It was easy to mock his diminutive stature, especially during his televised appearances on mid-80s music award shows, when his mountainous bodyguard would clear a path for the petite purple-robed idol to take the stage in high heels and pompadour and murmur thanks to God. He blurred his identity with pseudonyms and alter egos (Camille, Spooky Electric, Jamie Starr, Alexander Nevermind) and used a lot of "Eye," "4," and "U" in his song titles. It took baby boomers a while to get used to his particular brand of stardom. Now that he's gone and will obviously never be replaced, some of these idiosyncrasies are being re-evaluated in a more sympathetic light.

Prince made five feature films, starting with the electrifying and star-making Purple Rain, followed by an iffy attempt at classic Hollywood glamor, Under the Cherry Moon, and the unwatchably bad Graffiti Bridge. He was such a nonstop song machine that he cranked out not only his own albums and chart smashes but also a bounty of tunes for other artists, including his stable of proteges and side projects (The Time, Vanity 6, Apollonia, The Family, Madhouse, 3rdeyegirl) as well as songs like "Manic Monday" for The Bangles, "Nothing Compares 2 U" for Sinead O'Connor, and even "You're My Love" for Kenny Rogers. In the 2000s and 2010s, Prince continued to release music at a furious pace on a bewildering profusion of formats and platforms but rarely achieved the dominance he commanded at his peak. On April 21, 2016, at age 57, he died of an accidental fentanyl overdose at his home and studio compound, Paisley Park, setting off a worldwide outpouring of grief and tribute. (David Bowie had just died in January; it was a pretty depressing year all around.)

Culture critic Hanif Abdurraqib crystallized one of Prince's most surprising and transcendent moments in his essay "The Night Prince Walked on Water": his halftime performance at the 2007 Super Bowl in Miami, in the middle of a downpour. (When he was cautioned by the halftime show producers that it would be raining, Prince reportedly replied, "Can you make it rain harder?") A lot of people thought of him as a washed-up legacy act at this point, but he utterly demolished that notion with an unpredictable, virtuosic, and mind-blowing 12-minute set, delivered with easy grace. He opened with Queen's "We Will Rock You" and barrelled from there through "Let's Go Crazy," "Baby I'm a Star," and "1999," doing a call and response with the ecstatic stadium crowd. He swerved back to classic rock with a medley of "Proud Mary," "All Along the Watchtower," and the Foo Fighters' "Best of You" (the only time I have ever caught myself enjoying a Foo Fighters song). Then he concluded with a majestic "Purple Rain," just as the rain really started sluicing down. When Prince casually asks the crowd, "Can I play this guitar?" only one response is even thinkable. To an awestruck Abdurraqib watching it on his TV, the rain seemed to be falling around Prince. "Let us first speak of how nothing that fell from the sky appeared to touch him… This was Prince on a stage slick with rain, walking on actual water. There are moments when those we believe to be immortal show us why that belief exists." It's often ranked as the greatest Super Bowl halftime show ever.

The first time I ever heard the music of Prince was when I was 12, on a road trip through New Mexico in the family station wagon. My parents had not kept up with pop music since the Beatles, and my siblings and I were similarly innocent of the latest sounds. For some reason, driving through the desert that day, we had all become caught up in a whirl of giddiness and camaraderie that overcame our usual stress and bickering. In a burst of road trip high spirits, my dad suddenly said, "Let's turn on the radio!" That was something we never did. He was probably expecting some kind of good-time oldies to come bopping on to match our cheerful mood. But this was 1984: what came on was the cavernous, wracking incantation of "When Doves Cry." We had never heard anything like that before. Really, no one had heard anything like that before, not even people who listened to the radio all the time, because nothing much like that had ever existed. Prince's eerie squeals and mincing keyboard ravished us with portents of filial disaster, transfigured into lashings of erotic pleasure and pain. We sat there hypnotized by this doomy funk laceration for a few bars, and then my dad said, "Maybe we shouldn't listen to the radio," and snapped it off. We drove on in a very awkward silence. Every so often as a kid, I would catch a teensy glimpse of the artistic potential of pop music and vow to myself that I would learn all about it someday.

"When Doves Cry" did not start out that way. In a Pitchfork interview, Peggy McCreary, Prince's longtime engineer at Sunset Sound, recalls him first overstuffing the song with blaring guitars and synths, then subtracting track after track, hollowing it out into a minimalist masterpiece. Finally, he removed even the bass track; by ordinary pop music standards, it was practically Throbbing Gristle. It shouldn't have made it onto the radio, but of course, it was a massive hit.

Nor did Prince's music generally start out that way. Despite his stormy upbringing and the strife between his parents chronicled in the movie Purple Rain, his first two albums brimmed with the untroubled disco sounds of the late 70s, although written and arranged on a very high level—"I Wanna Be Your Lover," "Why You Wanna Treat Me So Bad," "I Feel For You." Somehow, the teenage Prince had extracted a contract from Warner Brothers that gave him total creative control, and he produced it all and played every instrument. At first, label executives were concerned about whether young Prince should be allowed to commandeer the studio and single-handedly make his own albums. The story goes that one night, they sent in a veteran producer disguised as the janitor to spy on what he was up to. He reported back that they had nothing to worry about.

After some hard-knocks touring as Rick James' opening act and being exposed to punk and new wave along the way, Prince made his first big self-transformation. On the 1980s Dirty Mind, he hauled the mild sexual innuendos of his early songs out into broad daylight on potent blasts of X-rated pop like "Sister" and "Head" (not to mention the 60s garage-style nugget "When You Were Mine" soon to be covered by Cyndi Lauper). He originally turned in Dirty Mind as a demo and then decided to pretty much release it as-is, with raw sound, ragged harmonies, and all. The black and white cover image captured his current look—trenchcoat, thong, high boots, spiky hair, and eyeliner. The Rolling Stones invited him to be one of their opening acts on their 1981 tour, but it was not a good fit—Stones fans did not take to the unusual newcomer and booed him off the stage after three songs.

Controversy was a return to throbbing funk, hyping his own willingness to cross boundaries—"Am I black or white, am I straight or gay?" Prince used to tell interviewers that his father was half-Italian and his mother was of mixed race; this turned out not to be true. But it was important for him to situate his image beyond the music industry's segregated categories at a time when MTV, for example, refused to play songs by black musicians. He certainly incorporated rock and new wave influences into his look and his music. His band was biracial, and soon enough, he would smash industry segregation and cross over to everyone. One of Prince's primary missions was always liberating sexuality and sexual experimentation from the repressive Christian conservatism of the 80s. Somewhat like David Bowie in the glam era, he rarely demonstrated any actual non-heterosexual tendencies, but his look and sound were very inspirational to queer fans, and he foregrounded queer musicians Wendy and Lisa in his band. Many years later, when he converted to Jehovah's Witness, he made some unfortunate proclamations about homosexuality being against the will of God, but for most of his career, he was a relatively audacious icon of gender diversity.

On his double album 1999, the sound and image really started to come together. He was gravitating more and more to the color purple, boldly splashed all over the cover, which also featured his own hand-drawn psychedelic lettering. It was the color of his beloved Minnesota Vikings, the color of Jimi Hendrix's "Purple Haze," the apocalyptic color of nuclear destruction ("the sky was all purple, there were people running everywhere"). The rocked-up "Little Red Corvette" and "Delirious" finally crossed over from urban to pop radio. Tour audiences and album sales were blowing up.

Prince was still jealous of the success of Michael Jackson, who was dominating charts, ticket sales, awards, and (eventually) MTV with "Billie Jean," "Beat It," and the juggernaut of Thriller. The two had a lot in common: they were almost exactly the same age, shy kids from tough Midwest families who idolized the same performers and grew up to be musical workaholics. Both played with notions of race, gender, and sexuality; both strove to transcend established pop categories and create a bold new sound, and both had to fight pervasive industry racism to do it. With two ambitious pop geniuses both trying to become the same kind of iconoclast at the same time, they naturally became rivals. (They also both struggled in their later careers and died early of drug overdoses.)

Their rivalry was mostly professional, and there were moments when it seemed like they might join forces. Prince skipped Michael's "We Are the World" session; a few years later, he was invited to duet on Michael's "Bad," but he scoffed at the lyrics and declined. There were also a lot of amusing stories about the two, like the time Michael visited Prince on the set of Under the Cherry Moon, and they got into an overheated ping-pong showdown. Michael had an odd sense of humor and enjoyed planting fake stories about himself in tabloids like the National Enquirer, such as that he slept every night in a hyperbaric chamber. My favorite of these was "Michael Jackson: Prince Is Using ESP to Drive My Chimp Crazy," in which he claimed that Prince was using his psychic abilities to drive Bubbles into a reign of terror. "Convinced Prince is monkeying with his monkey, Michael ordered his staff to scour the world for an ESP expert who can block Prince's mental messages to Bubbles—and told them price is no object..." Despite their rivalry, Prince and Michael always respected each other, and they both had a similarly liberating effect on 80s music.

To achieve Michael-like status, Prince decided he needed to star in his movie. He was already writing one, a drama featuring himself as The Kid, tormented by his parents' fraying, abusive marriage and locked in epic funk combat with Morris Day and The Time for dominance of the Minneapolis scene. They also battle for the affections of Apollonia, with The Kid wanting her for his girlfriend and sly, flashy Morris trying to get her to join his band. Despite roaring around on his purple chopper looking like a funked-up Louis XIV, it is not until The Kid allows Wendy and Lisa to help him explore his sensitive side on the magnificent "Purple Rain" that he finally brings the house down and wins Apollonia's love. Warner Brothers took a chance on funding it, and the result, of course, was purple pandemonium, catapulting Prince into the top rank of stars. The band-rivalry story masks the fact that Prince wrote every song in the film, from The Time's "Jungle Love" to Apollonia 6's "Sex Shooter." But these are vastly overshadowed by Prince's own epic songs, written in collaboration with his band: "Let's Go Crazy," "I Would Die 4 U", "Baby I'm a Star," ablaze with guitar licks and Bobby Z.'s clattering syndrums. Prince had become a cultural phenomenon.

After a whole year of Purple Rain insanity, Prince was ready to shed his Kid persona and move on to something new, even if his new fans weren't. He immediately baffled them with the psychedelic, lower-key Around the World In a Day, led by the string-swathed 60s throwback "Raspberry Beret." All his albums from the second half of the 80s have aged well and still sound amazing, even if they seemed like strange departures at the time. He would ditch his band, The Revolution, for the soundtrack to his next film, Under the Cherry Moon, an attempted 1930s-style black and white romantic comedy set on the French Riviera, in which Gigolo Christopher Tracy tries to win the love of a wealthy industrialist's daughter and is gunned down in the end. The film was a flop, but fortunately, the soundtrack album featured the stripped-down classic "Kiss." His albums became mystical, playful, and expansive; if his early work was about sex, 1999 was about the end of the world, and Purple Rain was about stardom, then Lovesexy and Sign O'The Times fused these into a kind of mystical religiosity. Sign O'The Times , a Dylan-esque double album offering a searing critique of urban America alongside whimsical gems like "Starfish and Coffee" and "If I Was Your Girlfriend," is regarded by many as his greatest work.

Around this time, he was announcing and shelving projects almost as fast as he was putting out actual albums and hits for his stable—notably the Black Album (aka The Funk Bible), which was in part a response to the rise of gangsta rap. He wrote a conceptual soundtrack for Tim Burton's Batman. Graffiti Bridge was supposed to be a sequel to Purple Rain , but it was a dismal flop with some of Prince's worst material and vanished without a trace. In 1991, he assembled a new band, The New Power Generation, and put out Diamonds & Pearls, a smooth adult-contemporary classic. But the raw creativity of 90s hip-hop was stealing the spotlight and making him seem old-fashioned. Frustrated that Warner Brothers was more concerned with trying to replicate the Purple Rain cash cow than releasing and marketing his vast number of creative projects, he announced that he was changing his name to an unpronounceable symbol for his next album. Journalists started calling him The Artist Formerly Known as Prince. After a massive greatest hits package and one more album, he parted ways with Warner Brothers and started putting out music on his own labels.

For years, fans wondered at the untold treasures said to be lurking in Prince's massive "Vault" of unreleased songs, albums, and demos from the Warner Brothers era, kept under tight security at Paisley Park and touted by him to be as legendary as anything of his official releases. After his passing, Warner Brothers cut a deal with Prince's heirs and are now re-releasing his classic 80s albums with extra discs full of Vault material. It turns out that stuff is hit or miss, but a lot of it is very impressive and plenty of fun. I never got to go on a tour of Paisley Park, but I always enjoyed the story that Prince would receive guests in a room stocked entirely with his own unreleased rarities. "Let's put on some music… would you like to listen to some Prince?" Like his Vault, Prince's later decades were peppered with bright spots amongst many tedious, uninspired tunes. My favorite of his later albums is 2004's Musicology , which starts with the unstoppably funky James Brown-esque title track.

For the past few years, my favorite way to pay tribute to the Purple One has been Prince Night at the Moonlight Rollerway roller skating rink in Glendale, which happens every year in early June around his birthday. (This year, it was on June 1, so be sure to catch it next year if you missed it this time.) The Moonlight Rollerway has a special connection to Prince himself—in the 1980s and 1990s, he would bring the demo tapes over to the rink whenever he was in Los Angeles working on new material. They would close down to the public for an evening, set up candles all around the perimeter, turn out the lights, and Prince would skate around for hours, testing out the new songs on the sound system. It goes without saying he was an outrageous roller skater. Only the Moonlight Rollerway staff and Prince's entourage were allowed in the building, and some of those staff members are still around and will tell you stories of how magical it was getting to watch Prince twirl around the rink to his own demos. So every June, a multitude of purple-clad fans converge on the Rollerway and boogie down to hours of the incomparable, celestial funk of the one and only Prince. These days, it's the closest we can get.