What are "air rights," and why are they important to Los Angeles's iconic Central Library building? The short answer is that without the funds the City received for the sale of the development rights above Central Library, we might not have the Library building we have today.

Here's the story: When the Central Library opened in 1926, it was housed in a 260,000-square-foot building called the Goodhue Building, named after its architect, Bertram Goodhue. At that point, the building was state-of-the-art, but Los Angeles and the collection continued to grow. By the 1960s, the Goodhue Building was no longer big enough. Not only that, it lacked modern amenities like air conditioning, fire sprinklers, up-to-date wiring and plumbing, and parking—that part of the problem was "solved" in 1969 when the Flower Street Garden was turned into a parking lot.

The City and the Library started looking for solutions to the Goodhue Building's problems. The quest took decades. Some people wanted the Goodhue Building demolished, and a larger, modern library constructed on the same site. Others wanted the City to sell the building and its approximately 5-acre lot and use the funds to construct a new Central Library somewhere else. Various suburban locations were proposed.

A third group, architects and preservationists, wanted the Goodhue Building to be preserved, renovated, and expanded, citing its architectural merit. They were motivated in part by the 1960s demolition of such Art Deco masterpieces as the Richfield Oil Building, which was once across the street from the Library. They were determined to prevent any more such losses. The struggle to save the Goodhue Building gave birth to the Los Angeles Conservancy.

In 1983, after years of discussion, argument, and competing proposals, the City decided on a three-part project: Renovate and restore the original Goodhue Building, build an addition (the Tom Bradley Wing) that would more than double the size of the Library, and turn the parking lot on the Flower Street side into a garden again; one inspired by Goodhue's original garden.

Financing was a key issue. Some funds for the preservation and renovation of historic structures were available from various governmental sources; however, these funds were limited, as were City and State resources, due to a national economic downturn and the 1978 passage of Proposition 13, which negatively impacted the State and the City. Much more money was needed.

Enter Robert Maguire, whose firm, Maguire Thomas Partners, was very active in downtown Los Angeles. For years, Maguire Partners had wanted to build a 73-story skyscraper across Fifth Street from the Library, but couldn't get the required City permissions. The plan ran afoul of the City's limits on building size. Those limits were calculated through a comparison between the proposed floor area in square feet and the size of the lot ("Floor Area Ratio"). The Maguire lot wasn't big enough to justify 73 stories. To solve this problem, McGuire Partners looked to the Library and its air rights.

What are air rights? Property owners typically own the development rights to the space above that property—those are the air rights, and they can be transferred. In an air rights transaction, an owner sells the development rights to a buyer who wants to construct something larger than would otherwise be allowed. Cities often use this kind of transaction to raise funds for the renovation and preservation of historic buildings.

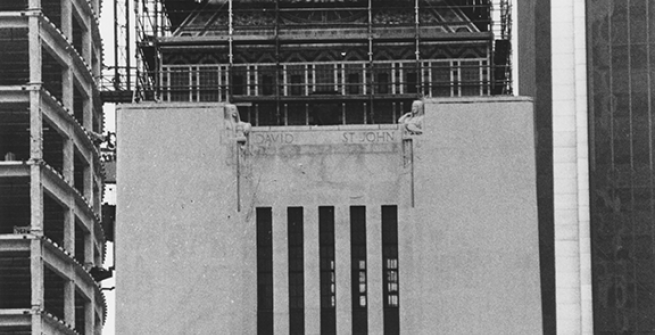

The Library site is substantial, with correspondingly significant air rights. If the Goodhue Building had been demolished and a new building constructed, that new building could have been much larger than the Goodhue Building and the Bradley Wing addition—but the City and the architect wanted to preserve the four-story profile of the original building. So, the City agreed to sell some of the air rights to Maguire for its lot.

After a long period of negotiation with the City, Maguire Thomas Partners paid $48.9 million for some of the Library site's development rights and a portion of the property—the Flower Street garden. (The City kept the right to use the garden.) It also agreed to other terms which increased the value of the deal to the City, such as the obligation to maintain the garden in the future. Another business, Lincoln Property, also bought some of the Library site air rights, paying the City $7.1 million. All that cash was a big part of the budget for the Library expansion, which totaled over $200 million.

Lincoln Property transferred its newly acquired rights to its property at 550 S. Hope and built what's now the KPMG Center. Maguire Thomas Partners built the 73-story U.S. Bank Tower. The building cost $350 million and is often referred to as the Library Tower. For years, it was described as "the tallest building between Chicago and Hong Kong." Later, it became "the tallest building west of the Mississippi River." It remained "the tallest building in California" until 2017, when it was overtaken by the new Wilshire Grand, which stands at 7th and Figueroa.

With the money that the City received from Maguire and Lincoln Property, and funds from other sources such as city bonds, foundations, and other private parties, the Goodhue Building was renovated, modernized, and restored, and the Bradley Wing was added. The renovated Library reopened in 1993. The joint structure composed of the historic Goodhue Building and the Bradley Wing is now called the Richard J. Riordan Central Library.

Please join us for a docent-led tour of the Central Library.

By Sharon Lybeck Hartmann, LAPL Docent, revised by Dave McMenamin, LAPL Docent