Women’s work—inside and outside the home—has always been a part of American life. But the reality of work has not always been easy. Through marches, strikes, boycotts, and organizing, women have fought for fair wages, safer working conditions, and equal treatment under the law. In honor of Women’s History Month, here are a few "firsts" achieved by women in their contribution to the American labor movement.

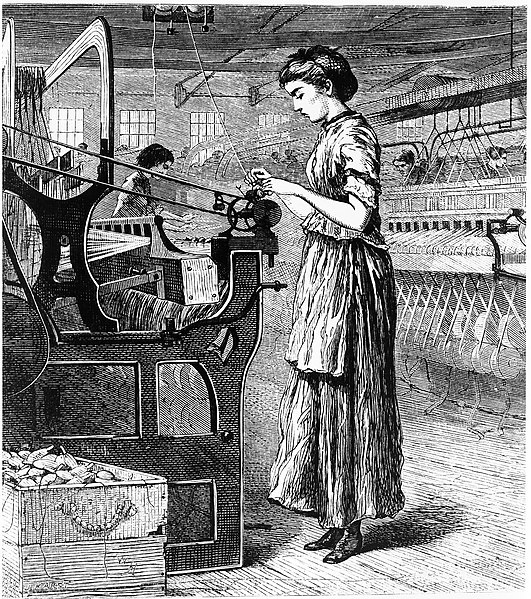

The First Women Factory Workers

During the early 1800s, thousands of free young women left their parents’ farms to go work in the fledgling textile factories opening up throughout New England. They often worked 12 hours or more per day, six days a week, earning about $2 weekly plus room and board. The job offered young women a new taste of freedom and the opportunity to earn a wage outside of the home in nondomestic work. However, conditions were harsh, noisy, and generally unsafe. Their lives off the clock were closely regulated by company-hired "house mothers" who lived with them in the boarding houses. Any type of infraction on or off the job would lead to being let go. Fired workers were then blacklisted in the industry by having their names circulated around all the mill towns.

Demands for better pay and more humane work environments quickly sprung up. In 1824, about 100 women weavers factory workers in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, walked out alongside male co-workers to resist wage cuts and extension of the workday, marking the first time that American women workers participated in a strike. They were defeated. After a week’s strike, the women were forced to return to work with a longer workday and a pay cut. Four years later, in December 1828, women factory workers struck again, this time on their own, at the Dover Manufacturing Company in New Hampshire. Over 300 women walked off the job protesting new rules such as a ban on talking or docked pay for being even one minute late. It appears that they were successful in having these rules rescinded. At this time, the union movement was starting to gain ground, but it was a movement largely for and by men. Women workers and their needs were generally ignored by organizers, so they took matters into their own hands. Between 1824 and 1837, at least 12 strikes took place in textile mills where women were the main participants. What made these strikes so remarkable was not for being successful—they weren’t—but for happening at all.

The mill town of Lowell, Massachusetts, which was the first planned industrial city in the nation, became a hub for labor organizing among women factory workers (called "operatives") of New England. In 1834, between 700 to 800 Lowell operatives "turned out"—went on strike—to protest a proposed pay cut. In 1836, under the guise of the Factory Girls’ Association, Lowell operatives turned-out again to protest an increase to their room and board costs. This time there were over 1500 strikers, and the turn out lasted much longer. They marched and sang a protest song with the lyrics:

Oh! Isn't it a pity, such a pretty girl as I,

Should be sent to the factory to pine away and die?

Oh! I cannot be a slave; I will not be a slave,

For I'm so fond of liberty,

That I cannot be a slave.

The Factory Girls’ Association eventually reached 2500 in membership. Their strike was broken once they ran out of funds to keep paying their room and board without paychecks. While the 1836 turnout was unsuccessful in meeting the strikers’ demands, they did disrupt production which was felt by the mills’ owners for several months.

The Factory Girls’ Association eventually evolved into the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association (LFLRA), becoming the first permanent union of women workers. Founded by Sarah G. Bagley and other operatives in 1844, the LFLRA became involved in the broader labor movement of the day, in particular the 10-Hour Movement (demands for a maximum ten-hour workday). The LFLRA largely shifted its focus from strikes to political advocacy. Though unable to vote, they petitioned and testified before the state legislature on matters of pay and workplace conditions.

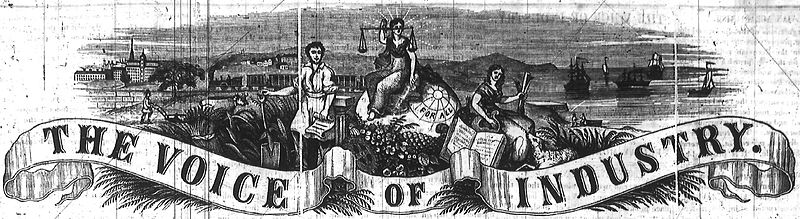

Bagely herself was a woman of many “firsts” in the labor movement. She was the first woman delegate to a labor federation convention, representing the LFLRA at the New England Workingmen’s Association convention in Boston. She was also the first editor of the labor weekly newsletter The Voice of Industry that served as an alternative to the employer-sponsored Lowell Offering which Bagley called "a mouthpiece of the corporations."

Bagely traveled throughout New England, recruiting LFLRA members from various mill towns and organizing signed petitions sent to lawmakers. She later went on to become the first female telegraph operator in Lowell. Ultimately, Bagely and the LFLRA were not particularly successful in their petitions. In 1847, they saw a small victory with a 30-minute reduction in the workday. But economic recessions, overproduction, and increased competition continued to drive down factory wages. By 1848, the LFLRA had dissolved with few goals realized. But the organization’s lasting impact was the emerging sense of women’s place both in the workforce and the burgeoning labor movement.

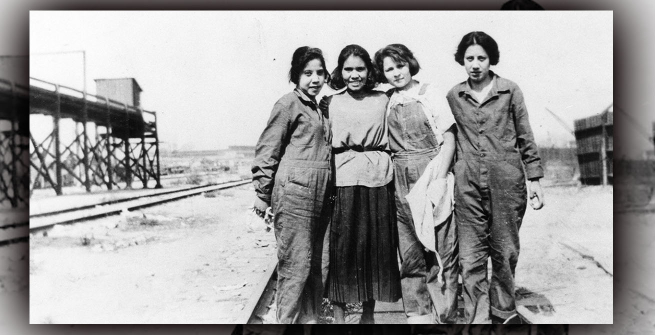

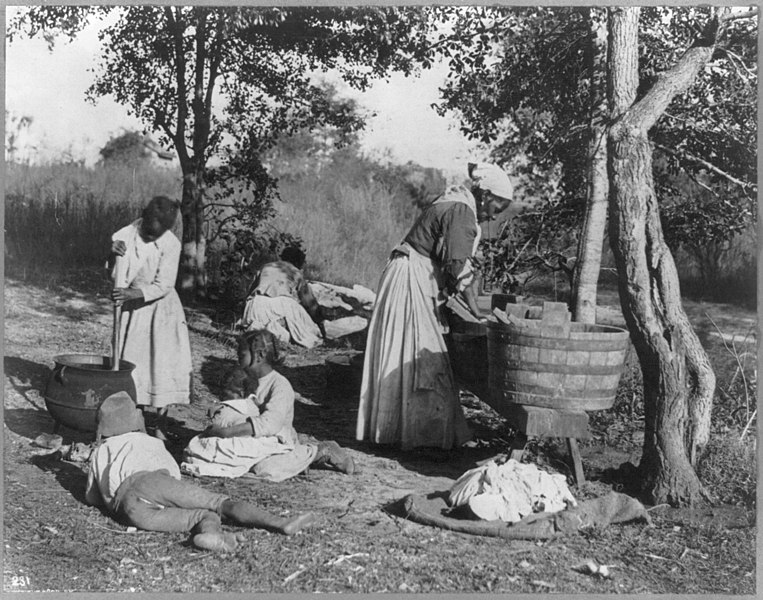

The Washerwomen of the South

“We do not wish in the least to charge exorbitant prices, but desire to be able to live comfortably if possible from the fruits of our labor.”

This was the statement made by laundry workers of Jackson, Mississippi, in an open letter to the city’s mayor on June 20, 1866. Signing their letter "The Washerwomen of Jackson," this marked the first known collective action of free Black women workers, as well as the first union organized in the state of Mississippi. At the time, nearly all Black female workers in the South were employed as domestic workers, with laundry service as the largest area of employment. Washerwomen were essentially independent contractors, bringing laundry into their homes and being paid a set rate by their clients for weekly service. This arrangement allowed them some flexibility and autonomy, but the work was labor-intensive, backbreaking drudgery that fetched extremely low pay. The Washerwomen of Jackson, merely one year out of slavery, were remarkable in their ability to form a network that laid out their demands.

In their petition, which was published in the local newspaper The Daily Clarion and Standard, the washerwomen suggested a uniform rate for their labor, and further stated that any washerwoman who charges less will be fined by their group. They requested the mayor’s support in their efforts. The media blasted them, calling their prices exorbitant, criticizing their skills and intelligence, and suggesting the petition was the work of northern White male agitators. There is, unfortunately, no surviving record of the group and whether or not their petition was successful. However, the inspirational event was a precursor to other actions by Black domestic workers in the American South. One of the more notable events was the Atlanta's Washerwomen Strike of 1881.

As described in Tera W. Hunter’s To 'Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women's Lives and Labors After the Civil War, this event began in early July 1881 when a group of about twenty washerwomen met up in a church to discuss forming a union. Calling themselves the Washing Society, they established higher uniform rates for their work, and relied on church ministers to spread the word to other laundry workers. On July 19th, the Washing Society called a strike in order to achieve their demanded rates. This was by far the largest protest of Black workers in Atlanta up to that point. Because so many households relied on laundry workers' labor, the entire city of Atlanta was affected by the strike. The Washing Society recruited through door-to-door canvassing, and within three weeks the group swelled to 3,000 strikers and their allies.

The city of Atlanta found formal and informal ways to punish the strikers. Landlords raised rents on their tenants who participated in the strike. The media disparaged them. Strikers were arrested or fined for disorderly conduct. Echoing charges from Jackson in 1866, the police chief claimed that White men were secretly leading the protest. Businessmen raised funds to open an industrial steam laundry to undercut the washerwomen. But commercial laundry operations were in their infancy and could not keep up with the demand for manual laundry services. The strikers had significant leverage that threatened the social, political, and economic establishment. Then in August, the City Council debated a resolution to impose an annual business tax of $25 on any washerwoman organizations, while at the same time providing a tax exemption for commercial laundries. In a letter to the mayor, the Washing Society called the Council on their bluff by agreeing to the annual fee in exchange for "full control of the city’s washing at our own prices…We hope to hear from your council on Tuesday morning. We mean business this week or no washing."

Historical records indicate that the Council backed away from the annual fee proposal. It also appears that the washerwomens’ efforts inspired other Black workers in the city. Rumors of another strike of household workers began to form in the fall. The second strike would have coincided with the International Cotton Exposition set to start on October 5th. This exposition was meant to be good PR for post-Civil War Atlanta. A strike of Black household workers, many of them former slaves, would have been a huge embarrassment to the city. History shows that the exposition went off without a hitch, so any rumored strikes probably did not come to fruition. Like the textile factory workers several decades earlier, the Washing Society’s "win" may have been largely symbolic. Whether or not the washerwomens’ efforts resulted in higher pay, they had not backed down and strongly frustrated the elite of Atlanta.

Garment Workers of NYC

At the turn of the last century, New York City was the capital of the garment-making industry. The workforce was predominantly made up of immigrants, with about half being Yiddish-speaking Jewish workers. It was also a female-dominated industry, where women were 7 out of 10 workers. Work conditions were absolutely terrible. The facilities were unsanitary and crowded. Employees labored at least 65 hours weekly and up to 75 hours during the busy seasons. They were often required to supply their own work materials like needles and thread. They were then docked pay for even minor mistakes. Women workers had it especially bad as they were paid significantly less than men for the same work. Additionally, despite their capabilities, they have shut out of the higher-paying pattern maker and cutter positions filled by men.

Among all of the bad garment industry employers, the Triangle Shirtwaist Company was one of the worst offenders. Employees only had one break during the 14-hour workday. During this time, they had to leave the building to use the outside toilets. The steel doors leading to the outside of the building were then locked to make sure workers didn’t take unauthorized breaks. Sometimes employees had to relieve themselves on the factory floor if they were not allowed outside. In June 1909, a fire prevention specialist sent a letter to the factory owners regarding safety concerns, but the letter was ignored.

By the end of September 1909, the garment workers of the Triangle Shirtwaist Company had had enough. With the backing of Local 25 of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), they went on strike, seeking higher wages, reduced hours, and union representation. Some of the Triangle workers had belonged to labor unions in Europe and were not unaware of union organizing tactics. Many of these women had radical politics and active supporters in the suffrage movement. After five grueling weeks, the strike was about to spread to other shirtwaist company workers.

Several hours into an ILGWU meeting on November 22, 1909, 23-year-old garment worker Clara Lemlich rose to the podium and declared in Yiddish, "I have no further patience for talk. I move we go on a general strike!” An industry-wide strike was declared. Two days later, when thousands of shirtwaist makers walked off the job, it became the first mass strike of women workers in U.S. history. The strike came to be known as the Uprising of the 20,000, although thousands more are estimated to have participated. The strikers were supported by the Women’s Trade Labor Union, a reformist organization made up of privileged suffragists.

Initially, the press did not pay the strike much attention. But then, in December, upper-class women (including Anne Morgan, the daughter of powerful financier J.P. Morgan) took up the strikers’ cause. Once members of this “mink brigade” began marching -and even being arrested- alongside the garment workers, the newspapers began publishing accounts of the dire conditions in the garment factories. Factory owners saw that they were losing the war of public opinion. By February 1910, the majority of factory owners had come to an agreement with the strikers. Though not a complete victory, the garment workers had achieved many gains, including a shorter work week, free tools and materials, paid holidays, and equal treatment of union and non-union employees. By the end of the strike, 85 percent of all shirtwaist makers in New York had joined the ILGWU. The event has been considered the first successful mass uprising of workers and an important milestone in the growth of unions in the United States.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Company was one of the few employers that had held out and refused to make an agreement with the union. Garment workers returned to work while safety concerns continued to be ignored at the factory. Then on March 25, 1911, a devastating fire broke out in the building. Because the doors and the stairwells were locked to prevent unauthorized breaks, many of the workers could not escape. Tragically, the fire caused the deaths of 146 garment workers. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire has become known as one of the worst industrial disasters in the nation’s history. Although it came too late for the victims, the fire led to improved factory safety laws and spurred a growing support for the ILGWU, which continued to be one of the most prominent unions throughout the 20th century.

Enduring Impact

The New England textile factory workers, the washerwomen of the South, and the garment workers of New York showed tremendous bravery and political savvy at a time when workers had few rights and women were largely ignored by male-led unions. These stories are a snapshot of some of the contributions of women to the American labor movement, but they are by no means a comprehensive history. Fortunately, the library has a wonderful collection of material on this topic for further reading. For more stories like these, follow the links above or check out the titles in the list below.