June 16 marks Bloomsday, a day of celebration in honor of Irish writer James Joyce’s seminal novel Ulysses (1922). This year marks the centenary of the publication of the work which may be most famous for being the one novel most readers start and slog through but rarely finish. Bloomsday is named after the titular character Leopold “Poldy” Bloom. Thousands of events in Dublin and the world over celebrate the characters in the novel with marathon 30+ hour readings, film screenings, pub crawls, lectures, and all sorts of festivities. Recognized as one of the most important works in the English language, the publication history of Ulysses is itself a drama worthy of an exploratory revisiting.

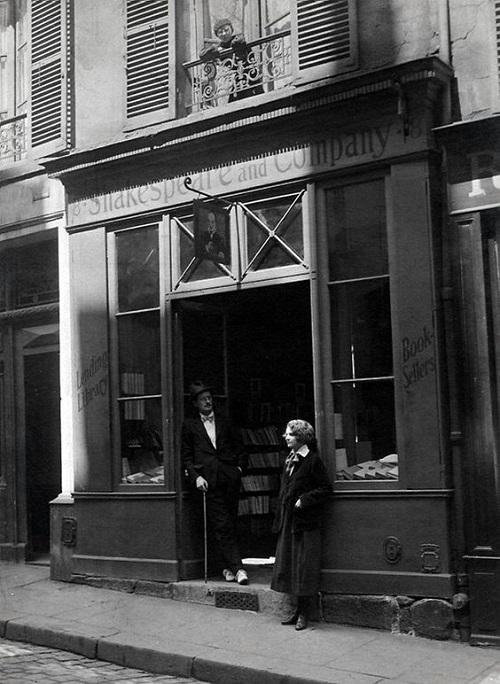

Who would have thought that one of the movers and shakers of the Western literary world would be a girl from Baltimore? Sylvia Beach, a Presbyterian pastor’s daughter, grew up in New Jersey with dreams of moving to Paris, then the literary hub of Europe, with an "obsession" to have a bookshop of her own. Soon, her rag and bone shop Shakespeare and Company became a haven for ex-pats, iconoclasts, and the wayward, among them Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, the Pounds, Sherwood Anderson, Ernest Hemingway, Samuel Beckett, Louis Aragon, and countless others who Beach affectionately called "the crowd." To this day, the bookshop on the Left Bank of Paris (although not its original location) serves as a haven for anyone willing to put in some work for a cozy bed and historic board. In her charming book, Shakespeare and Company, Beach notes that “every boat from the other shore brought more customers for Shakespeare and Company” and that these “wild birds” were enticed by the presence in Paris of Joyce, Pound, and Picasso. The self-professed "Mother Hen of the 20s" jokingly remarked that with all the comings and goings, "I can hardly get any work done!" What an absolutely exhilarating time Paris of the 1920s must have been. And despite the notable interruptions, get work done she most certainly did.

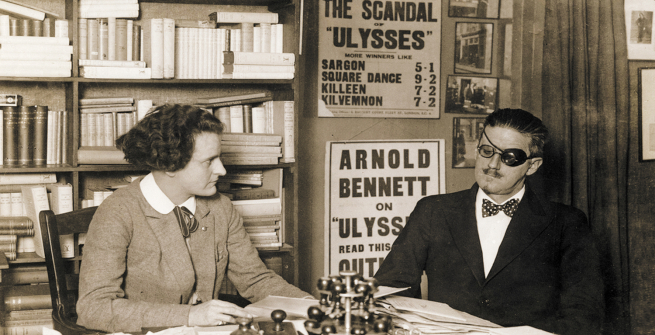

By the summer of 1920, when her bookshop was in its fledgling year, Sylvia Beach met James Joyce for the first time and logged "James Joyce: 5, rue de l’Assomption, Paris; subscription for one month; seven francs" when he signed up for her budding lending library. She called him the bookshop’s "most illustrious" member, "never at all standoffish" and found him to be an easy conversationalist and very charming. Joyce soon became a daily visitor to the bookshop on 8, Rue Dupuytren in the Saint Germain district.

Joyce spent seven years writing Ulysses, but the real battle was getting it published. The novel began appearing serially in The Little Review, but there were complaints about the "suitability" of the novel, and legal objections abounded. The magazine was seized by the United States Post Office on grounds of obscenity, which drove a dagger into hopes that the novel would be published in the English-speaking world.

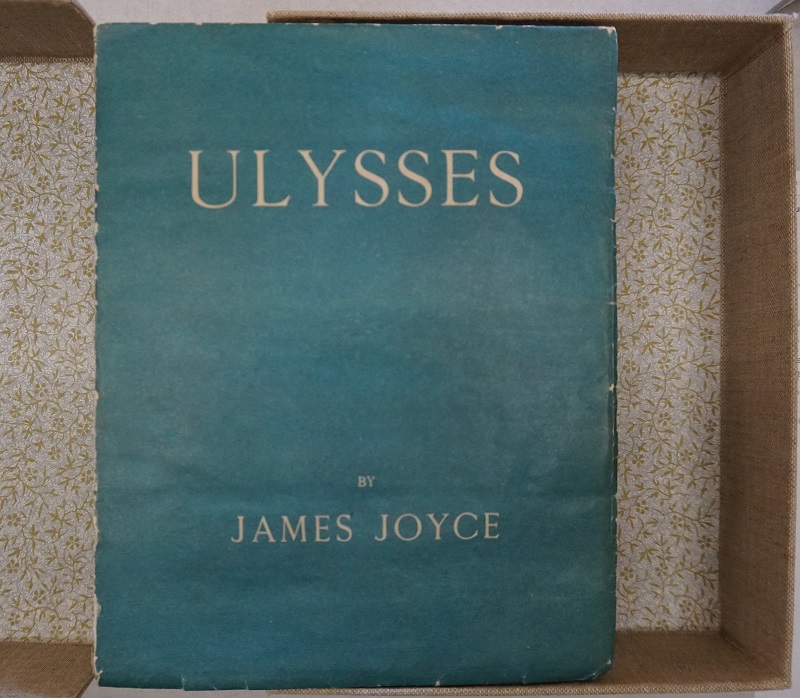

Sylvia Beach, hearing the discouragement firsthand from her daily visitor, asked, "Would you let Shakespeare and Company have the honor of bringing out your Ulysses? to which Joyce quickly replied "I would!" thus entrusting his great work to, by her own account, an inexperienced and “funny little publisher.” Thus, quite inauspiciously, and with the naivete of a feisty woman with no experience in publishing, one of the most seminal works of the English language found its champion. And thus began a two-year trial of endless proofs and re-edits, resulting in tests of patience for the publisher and worsening vision for the author. Finally, on February 2, 1922, Joyce’s birthday, Sylvia Beach proudly handed the author Copy No. 1 of Ulysses.

Joyce was understandably most appreciative and even giddily helped with mailing out parcels of the book (he discovered that they weighed one kilo, 550 grams each) as the novel was in high demand. In her book Shakespeare & Company, Sylvia Beach recounts how glue from the mailing labels got in Joyce’s hair, so dedicated was he to the process.

A stateside edition would come much, much later. US Judge John Munro Woolsey’s 1933 opinion finally lifted the US customs ban on Ulysses, and Random House printed the first US edition of the novel in 1934, with his opinion in the preface.

Now a little about the novel, which has been dissected and deconstructed by countless scholars. Ulysses is the Latin form of Odysseus, the hero of Homer’s Greek epic, and the titles of the chapters in the work are named after characters found in the Homeric poem. The Odyssey spans a decade while Ulysses logs a total of 18 hours on June 16, 1904, the day Joyce met his wife and muse, Nora Barnacle. Joyce’s father was said to have cheekily quipped "she’ll never leave you!" when first introduced to her.

The novel begins with the precocious young writer Stephen Dedalus, and by the fourth chapter, we’re introduced to Leopold Bloom, a likable but not altogether cerebral fellow who becomes friends with the serious author. The work basically chronicles a rather ordinary day in the life, in a style which is anything but ordinary.

There are certainly parallels between Homer’s epic and Ulysses, with common themes of father and son atonement and homecoming, but Leopold Bloom’s wife Molly (modeled after his muse Nora) has extramarital sex (with Blazes Boylan), unlike Penelope in The Odyssey who is celebrated for her faithfulness. The novel is written in stream-of-consciousness style with the narrator jumping from thought to thought, although Joyce explores and has fun with many literary styles.

In the chapter Aeolus, we find ourselves in the newspaper offices of The Evening Telegraph, and references to wind and windbag journalists abound. In the parallel universe of Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus finds himself on Aeolia where Aeolus, warden of the winds, gives him a magic bag containing all the unfavorable winds that may steer him off course, so that he can go without hindrance straight to Ithaca. Odysseus is exhausted after 10 days of sailing and falls into a deep slumber with the shores of Ithaca in sight. Sailors on the ship wonder what treasures he is hoarding in his bag, and they open it releasing the winds that then blow them all straight back to Aeolia. Joyce plays with the idea of the cacophony and noise surrounding the politics of the day, where allegiances blow this way and that, just like the winds.

The final chapter, referred to as Penelope, consists of eight very long sentences with Molly’s famous soliloquy. We’re in her head, and Bloom is in her bed.

I was a Flower of the mountain yes when I put the rose in my hair like the

Andalusian girls used or shall I wear a red yes and how he kissed me under

the Moorish wall and I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him

with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes

my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down

to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad

and yes I said yes I will Yes.

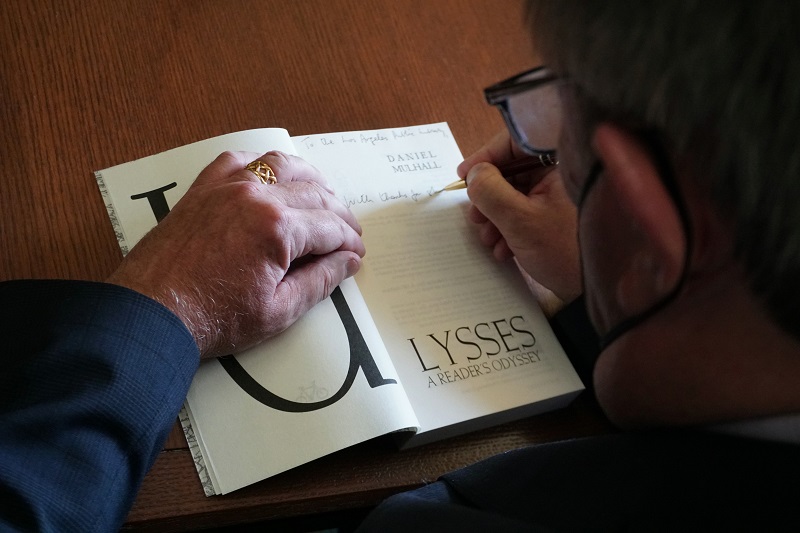

Last month, at the Central Library, we were thrilled to host the visit of Daniel Mulhall, Ambassador of Ireland to the United States. He is also a Joyce scholar and recently published the eminently readable Ulysses: A Reader’s Odyssey (which he graciously signed and gifted to our Library). We had the pleasure of hosting His Excellency in our Rare Books Room where we exhibited both our 1st edition of Ulysses, in its original Greek blue binding, and also an artists’ book entitled Wavewords which focuses on a short passage from the Chapter Proteus, where Stephen Dedalus urinates on a beach. By all accounts, our Irish visitors were delighted to see these fine examples of our special collections.

His Excellency also shared both a revelation and promise, which I’ll share with you all, dear Readers: the first being that if anyone is thinking of reading Ulysses but is daunted by it all (and let’s be real, that’s most of us) to feel free and skip the first three quite boring chapters and delve into the world of Leopold and Molly which begins with chapter 4. That was truly a revelation, and I began rereading my battered copy with gusto that same evening. Now the promise: he also graciously pledged to help us track down the provenance of our first edition, copy number 905. With that information, we’ll know who owned the book and how it likely ended up in our Special Collections.

Mulhall argues that it’s not Molly’s soliloquy which has the most famous last words of the novel, but "Trieste-Zurich-Paris, 1914-1921." After all, Joyce wrote his most Irish of novels in exile, and was never to return to Ireland. The streets, sights, sounds, and smells of Dublin are recounted purely from memory.

American George Whitman opened the Shakespeare and Company bookstore in its current location on Rue Bucherie, a stone’s throw from the Notre Dame Cathedral, in honor of Sylvia Beach in 1951. Sylvia Beach, champion of Ulysses and staunch advocate and friend of writers—namely one leviathan named James Joyce—remained in Paris until her death in 1962. Her contributions to the Western canon cannot be overstated. The bookshop still spreads a love of writing and kind company, which is also part of her enduring legacy.

![Shakespeare and Company, entrance to reading library, [2015].](/sites/default/files/media/images/blog-lapl/2022/SCO_Front_Lib_Be_Not.jpg)

Further Reading (and Viewing)

Spoo, Robert. “Judge Woolsey’s Ulysses opinion: early print history and reader response.” Journal of Modern Literature (vol. 43, issue 1)

Sylvia Beach interview on James Joyce and Shakespeare & Co (1962)