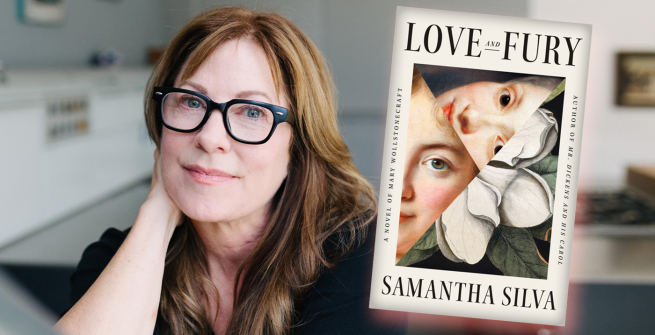

Samantha Silva is the author of the novel, Mr. Dickens and His Carol, and a screenwriter who has sold projects to Paramount, Universal, and New Line Cinema. She lives in Boise, Idaho. Her new novel is Love and Fury: A Novel of Mary Wollstonecraft and she recently talked about it with Daryl Maxwell for the LAPL Blog.

What was your inspiration for Love and Fury?

Everyone knows Mary Shelley, who gave us Frankenstein, but not everyone knows her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, who gave us feminism—who invented the life. I think they should. Wollstonecraft is an enormously important 18th-century writer and philosopher who fights with every shred of her being for an end to tyranny, whether of kings, of marriage, or men. She took Edmund Burke head on, supported the American and French Revolutions (though she thought the Americans didn’t go far enough), argued fiercely for gender equality, and lived as an independent woman, supporting herself as a writer, which is extraordinary for the period. She was famous in her own lifetime, but her reputation was destroyed for a century when her grieving husband, radical philosopher William Godwin, rushed to write a tell-all memoir—including her tragic love affairs, out-of-wedlock child, severe depression, and suicide attempts—that scandalized even her admirers. I think we’re still recovering from that loss—trying to recover her. Two centuries later, her fight for gender equality is still the fight, and her presence as necessary as ever.

Most of the “characters” in Love and Fury are based on actual individuals and historic figures. Are there any “characters” in the novel that are completely your creation? or any of the other characters in the novel inspired by or based on specific individuals?

Almost everyone is based on someone real, but the midwife, Mrs. Blenkinsop, is my own creation. (I’d read that Wollstonecraft had a midwife by that name, and thought, how could I beat that? It’s so Dickensian!) I’m quite deliberate when I plot, but Mrs. B surprised me along the way. Because of the dual structure of the novel, and the fact that it takes place over the eleven days between Mary giving birth and her death from puerperal fever, I needed the midwife to ground us in the present moment, to be a springboard for Mary to tell the story of her life. But Mrs. B also has an arc of her own that mirrors Mary’s in some ways. I didn’t know that when I started. She’s a character who also lives in a world circumscribed by men and men’s power, so her story evolved naturally. I felt very close to her by the end.

Mary Wollstonecraft lived during a very tumultuous time in the world (the American Revolution, the French Revolution, etc...). How familiar were you with the late 18th century and Wollstonecraft’s life prior to writing the novel?

It was an extraordinary time to be alive, especially for people who’d been arguing for revolutionary ideals for so long, often at great personal risk. I admit that I probably learned more about the American Revolution by watching HBO’s John Adams series than I ever did in school. At least that’s when it came alive for me, the way the French Revolution did when I read Hilary Mantel’s A Place of Greater Safety years ago. But one of the marvels of writing a novel about a figure like Wollstonecraft is experiencing the sweep of history through her, the fear, the danger, the thrill, the momentousness that was deeply personal. She moved to Paris, alone, to be a witness to post-revolutionary France, put her own neck quite literally on the line. She didn’t expect to be moved to tears when she looked out her window to see the king passing by on his way to certain execution, but it’s a detail that makes it real and reveals the complexity of living in that moment. I learned so much from moments like that.

If you had to do research, how long did it take you to do the necessary research and then write Love and Fury?

I’m that writer who thinks if I just read one more book, one more article, look at my notes one more time, then I’ll be ready to write. I didn’t know much about Wollstonecraft’s life when I started, so I devoured the great biographies, collected letters, her own writing. And again, I’m quite plot-driven, I think because I cut my teeth as a screenwriter. So, at some point I taped up a long piece of butcher paper across my living room wall, and brought out the multi-colored post-it notes, trying to capture what I thought were the plot points in her life, the experiences that formed her, that altered her trajectory, propelled her. I can’t pinpoint when I started to hear her voice in my head, but that’s when the writing begins, even if it’s not the beginning. (Twice I’ve written the beginning of a novel that turned out to be the end.) Altogether, it took me about three years, start to finish.

What was the most interesting or surprising thing that you learned about Mary Wollstonecraft, her work, or the time in which she lived/wrote during your research?

The thing that startled me was how modern Wollstonecraft was. It’s easy to fall into clichés—she broke rules, defied norms—and of course she’s a creature of the late 18th century, but still, there’s a kind of rage against injustice, against a world whose rules are made by men, that drives everything she does, that I see now in women all around me. She detests fashion, wears clothes the way she likes them, doesn’t frizz and powder her hair or adorn herself in any way, rejects the consumerism of the age, the objectification of women, barely eats meat, refuses sugar because of the slave trade, rails against marriage and sex that oppresses women. Maybe her first act of real defiance is laying her body across the threshold of her mother’s bedroom to protest her father’s nightly abuse. It’s a vivid reminder that #MeToo is a culmination of centuries. And that’s the corollary that startles me as well: how little, for women, things have really changed. Wollstonecraft thought that civilization, run by men, had utterly failed us. Well, here we still are. There’s so much work left to do.

How did the novel evolve and change as you wrote and revised it? Are there any characters, scenes, or events that were lost in the process that you wish had made it to the published version?

Funny, I do have a fantasy of publicly reading the opening of the novel that never made it in. It’s a chapter I’m proud of, that will never see the light of day because my editor’s smarter than I am. For a long time, I couldn’t shake the idea that Wollstonecraft’s story would be pieced together, discovered, through her daughter Mary Shelley, beginning on the night she starts Frankenstein. Because that book is so much about a child abandoned by its creator, and because Shelley was obsessed with her absent mother, I wanted to find the story of the mother through the daughter, somewhat in the way the grandson unearths his grandmother’s story in Angle of Repose. But again, everyone knows Shelley, and I needed to let her go to find Wollstonecraft in her own right. This is why we have editors.

Mary Wollstonecraft was clearly a woman before her time, challenging the societal norms that restricted women and their lives. Do you have an idea or theory regarding why she is mostly forgotten now (other than as the mother of Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein)?

This circles back to my first answer, about Wollstonecraft’s husband, Godwin, writing a memoir that destroyed her reputation for a century until Virginia Woolf resurrected her in 1929 and restored her to the pantheon, where she always belonged. Woolf found her “alive and active, she argues and experiments, we hear her trace her influence now among the living.” The feminist wave in the 1970s found her too, but it’s fifty years on, time to hear from her again.

What’s currently on your nightstand?

When I’m writing, my reading diet is pretty steadily of the period, or of the person. I have to be immersed; have to be thinking about it all the time. It takes me a while to venture out of that. It feels a little disloyal, like leaving a friend behind. But I also sense that the well is dry, I’ve used up my reservoir of words, and have to fill it with someone else’s for a while. There’s a lot I’ve missed. I just finished Alexander Chee’s How to Write an Autobiographical Novel, and Hamnet, both gorgeous. Other things in my pile: The Illness Lesson, Beloved, The Children’s Bible, Leaving Isn’t the Hardest Thing, Becoming Duchess Goldblatt, Susan Taubes’ Divorcing, a book of Chekhov stories, George Saunders’ Russian book, and still working my way through Jhumpa Lahiri’s In Oltre Parole (in my slow Italian)!

As a debut author, what have you learned during the process of getting your novel published that you would like to share with other writers about this experience?

It’s a very strange experience. I write alongside a full-time job, and so I’ve had to fit everything around that, including editing and publicity commitments. It makes for quite an odd combination because the whole situation feels both more normal than I was expecting it to, and also a lot more exciting. It can feel a little like whiplash going from an ordinary daily routine to something that I’ve been working towards for so long!

What is the last piece of art (music, movies, tv, more traditional art forms) that you've experienced or that has impacted you?

I’ve really missed going to the movies these many months, so going to our arthouse theater last weekend, buying popcorn, a glass of wine, sitting in a dark theater with five other strangers, that affected me a lot. We saw The Truffle Hunters, which I marveled at every moment. It’s beautifully made, there are frames of it like paintings, but it’s also funny and captures something special about that slice of Italian culture, something I worry may be lost in a generation or two. But I measure the impact of art by how much I think about it after the fact, whether it’s a painting or a song I can’t stop humming. After seeing the movie, I really wanted to understand how it worked. Even for a documentary, there wasn’t an obvious structure, a dramatic question, a climax. And then it hit me, each of the truffle hunters is like a short story of its own. A question is asked, a question is answered, but it’s so simple and subtle, you could almost miss how perfect it is. I love when art does that.

What is the question that you’re always hoping you’ll be asked, but never have been? What is your answer?

My guess is that this is a question for men because most women I know would think first of the question they’re always hoping they won’t get asked. For me it’s: What took you so long? I’m a woman of a certain age, and I feel like I’m just getting started. I understand why it happened, where I got distracted, but I’m filled with regret for the time I wasn’t honing my craft. I still think about getting an MFA, if it would make the writing better. And I see people who’ve been through that: they have a sense of community I don’t have. I’m a lone writer. I’m an introvert. I have remarkable friends, but I miss having writing peers.

What are you working on now?

I’m so happy to report that I’m working with Seattle Repertory Theater to adapt my first novel, Mr. Dickens and His Carol, for the stage. And I’m having the time of my life. It started as a screenplay, which I optioned four times, then found life as a novel, so it’s a dream to think of it as a play. And the experience of workshopping it with eight actors over Zoom for three days, well, I think every novelist would learn a lot about the flaws in their logic by doing that. An actor who has to say the lines will not stand for anything that doesn’t make perfect sense. I highly recommend it.