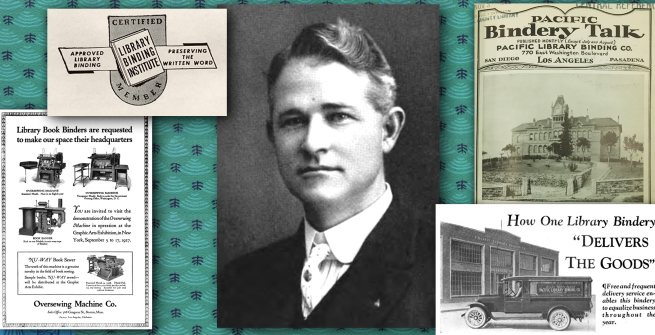

W. Elmo Reavis was a man who wore many hats, including bookbinder, instructor, inventor, manufacturer, editor, and advocate. He established the Pacific Library Binding Company in Los Angeles in 1912 to focus solely on bookbinding for libraries. For more than forty years, the Pacific Library Binding Company provided bookbinding services for a number of public, academic, and special libraries in California. Additionally, Reavis taught bookbinding classes at the Los Angeles Public Library Training School from 1913 to 1932 and at the Riverside Library Service School from 1914 to 1922. It was important to him that librarians understood bookbinding so they could make informed choices about what sort of binding, lettering, etc., they needed in order to maximize their binding budget. He shared bookbinding information with librarians on a larger scale with Bindery Talk, a monthly magazine dedicated to "Better Bookbinding for Circulating Libraries" that he started in May 1912. He also sought to improve library binding by patenting several pieces of bookbinding machinery that were used universally, and was instrumental in standardizing library binding nationally.

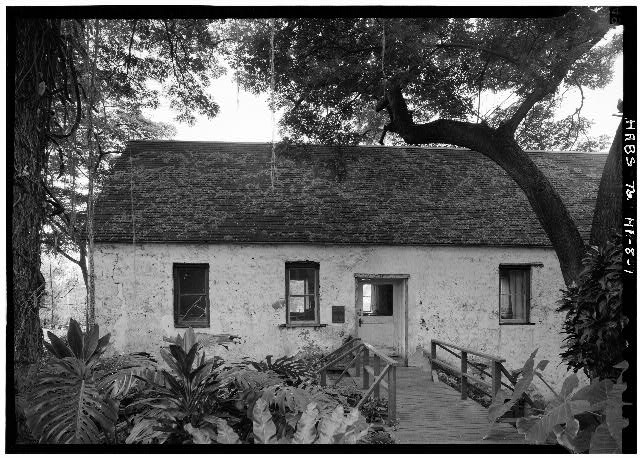

Winfred Elmo Reavis was born in 1877 to pioneer parents in what is today Whittier. He was educated in Los Angeles and graduated from the Los Angeles State Normal School in 1896. Following graduation, Reavis accepted a teaching position at the prestigious Lahainaluna Seminary in Honolulu. That school, founded in 1831, is now the oldest high school west of the Rockies. After a brief return to teach in Los Angeles, Reavis returned to Lahainaluna Seminary, where he became principal in September 1899.

The Lahainaluna Seminary had a printing shop where books for the seminary were printed, and the students were taught printing, engraving, and bookbinding. Reavis' predecessor, Osmer Abbott, started Hawaii's Young People magazine in 1897, which featured short stories, poetry, and Hawaiian history. Reavis subsequently became publisher (and occasional editor) of the magazine, which was printed in the school's print shop and served as supplemental reading for schools across Hawaii. It is possible that Reavis enjoyed printing and bookbinding more than teaching and being a principal—he retired from his position at the Lahainaluna Seminary in 1903 and moved back to Los Angeles.

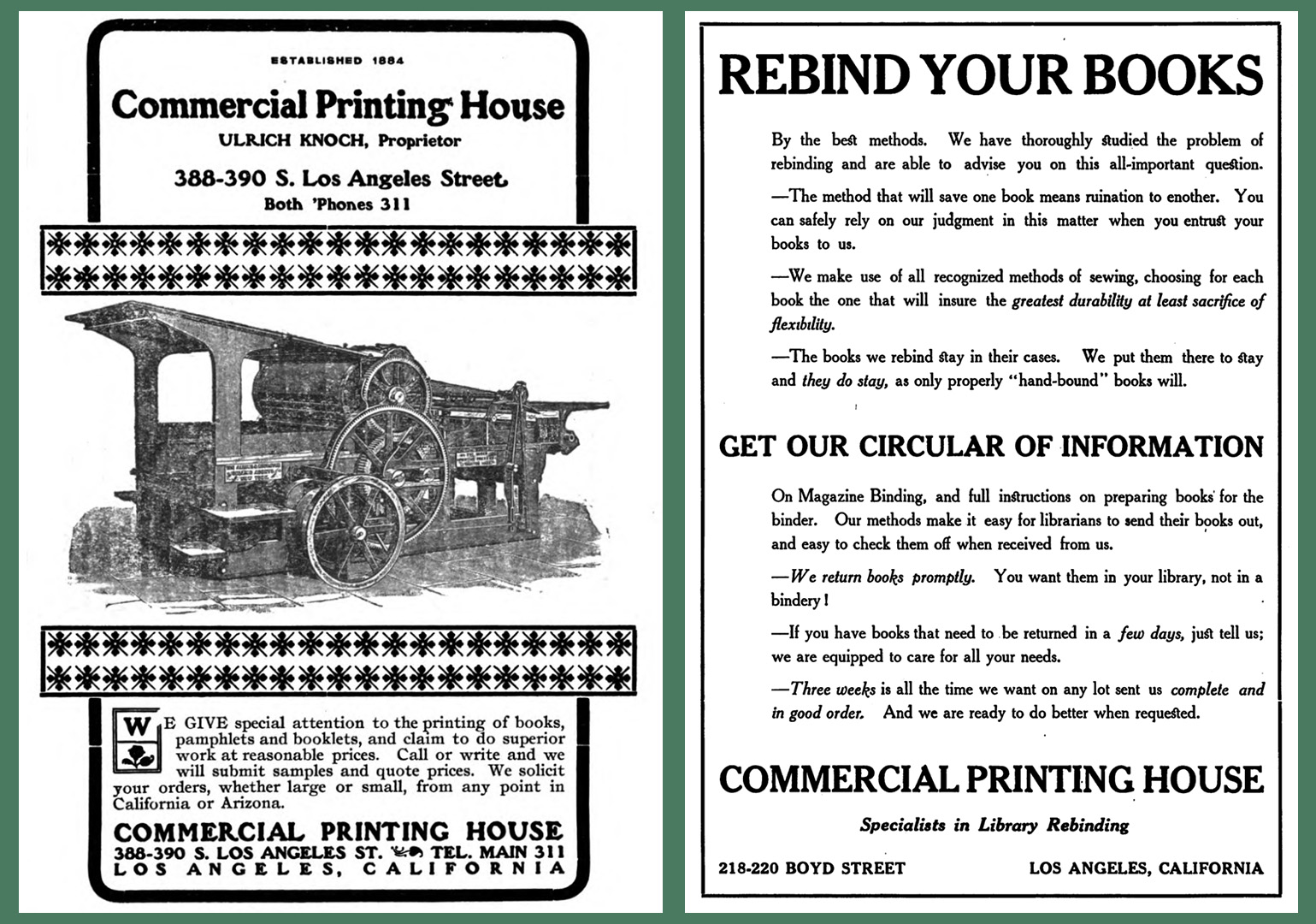

Over the next ten years, Reavis honed his printing and bookbinding skills by working for several different firms, including the Commercial Printing House, the Neuner Company, and the Segnogram Publishing Company. Interestingly, he was a clerk at the Neuner Company during the year they published Los Angeles, a Guide Book by Alice Mary Phillips (for the 1907 National Educational Association/NEA convention in Los Angeles) and Dana T. Bartlett's The Better City: A Sociological Study of a Modern City (about Los Angeles). Both books are available at the Los Angeles Public Library. From late 1907 until 1909, Reavis worked at the Segnogram Publishing Company. Their chief output was the work of "entrepreneur" (some called him a huckster) A. Victor Segno and his American Institute of Mentalism. But for the largest part of the first decade of the twentieth century, W. Elmo Reavis worked for the Commercial Printing House.

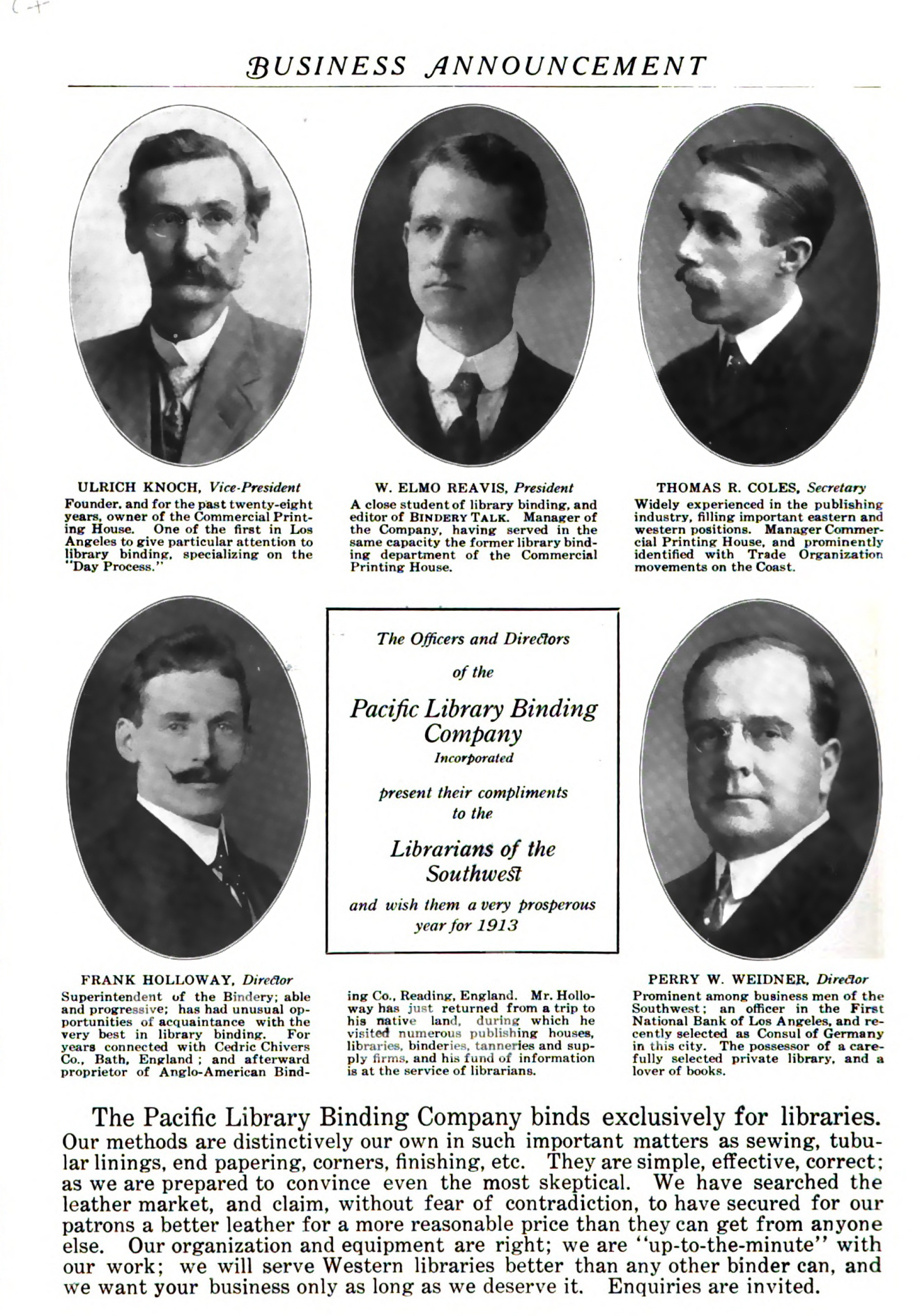

The Commercial Printing House, in business since 1884, was well-known for printing sheet music, books, and maps. Reavis worked there under Ulrich Knoch from 1904 until 1906 and returned in 1910 (the 1910 city directory listed Reavis as assistant manager and Thomas R. Coles as foreman). Reavis, Coles, and Frank Holloway (formerly with the renowned bookbinder Cedric Chivers of Bath, England) began specializing in library rebinding at a time when Ulrich Knoch was thinking about retirement.

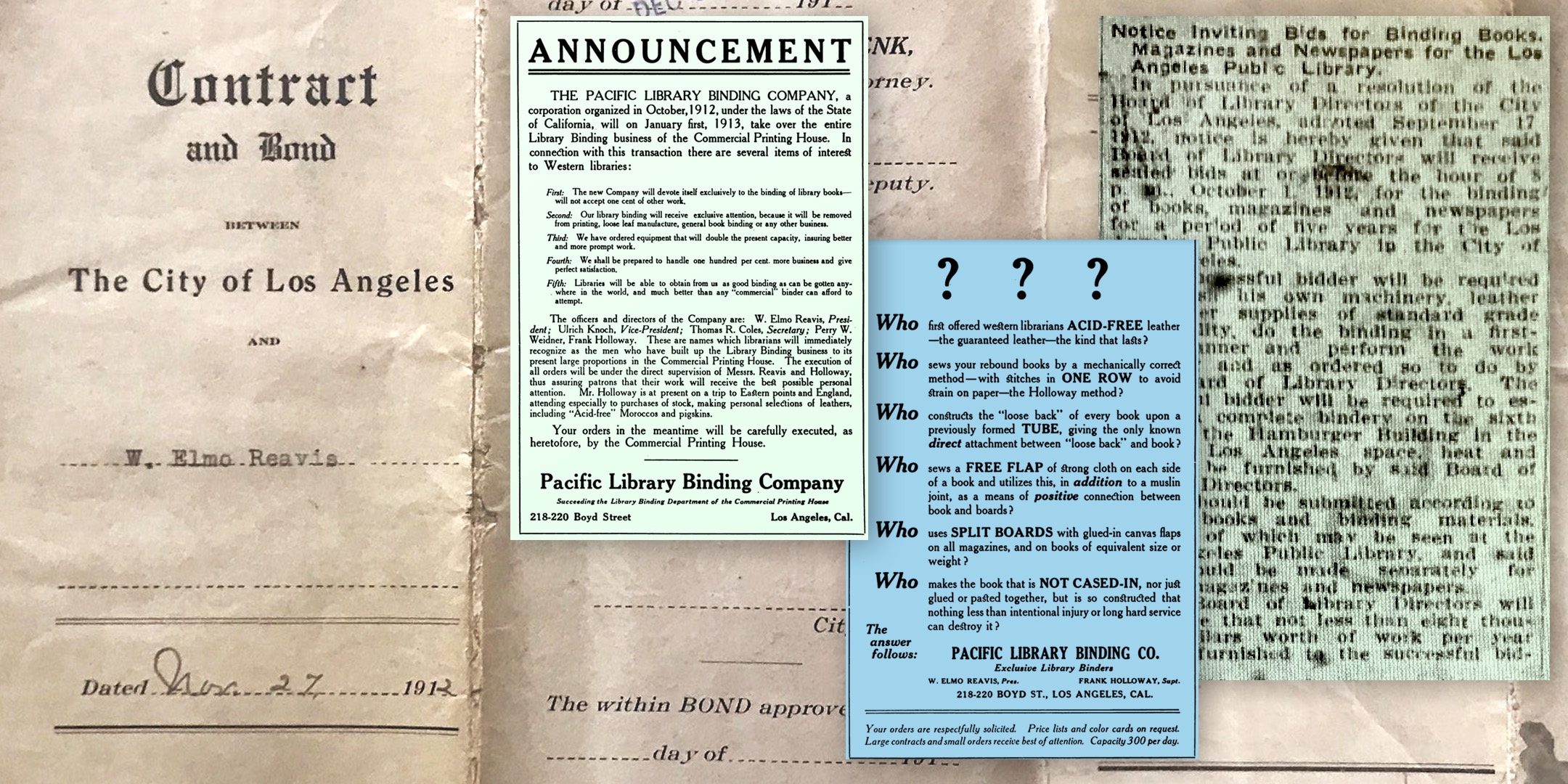

On September 12, 1912, an advertisement appeared in the Los Angeles Daily Journal seeking bids for a five-year contract binding books, magazines, and newspapers for the Los Angeles Public Library. What made this a unique contract was the fact that the bindery would be required to move their own machinery, leather, and supplies into the library, specifically onto the sixth floor of the Hamburger Building. Everett Perry, beloved City Librarian from 1911-1933, sought to make bookbinding more productive by moving an independent bindery into the library building for quicker, more cost-effective service. [It is worth noting that more books were rebound in the past, due to increased use (more checkouts) alongside the sometimes poor quality of paper and/or manufacturing. A 1934 Pacific Bindery Talk article described one library that expected to check out a book in its original binding only about 10-12 times, but they could check it out an additional 50-60 times when rebound.]

[Reavis] was aided [in starting Pacific Library Binding Company] by his former associates: [Ulrich] Knoch sold his equipment to the new bindery, [Thomas] Coles financed the venture, while [Frank] Holloway furnished his invaluable bookbinding experience gained here and abroad.

—Bookbinding & Book Production, May 1938

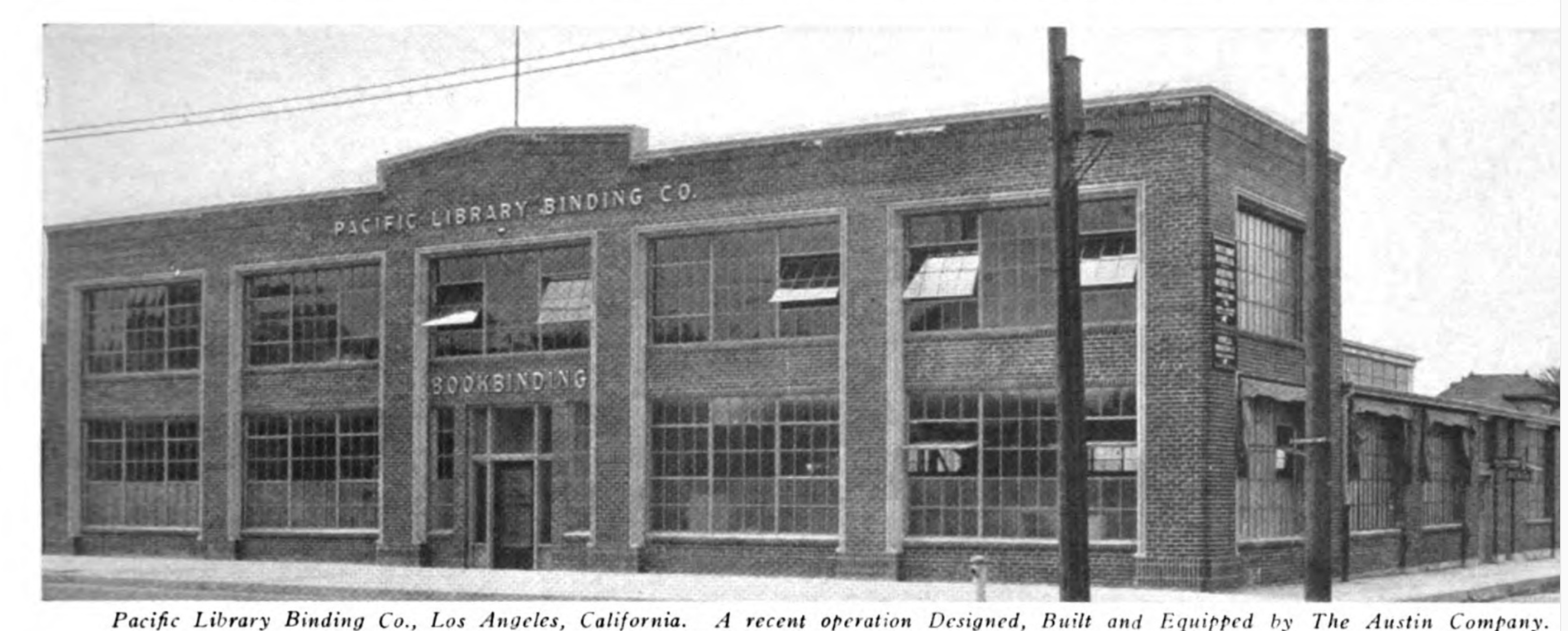

W. Elmo Reavis, with the help of colleagues from the Commercial Printing House, incorporated the Pacific Library Binding Company in October 1912 and successfully won the five-year contract with the Los Angeles Public Library. A separate bindery was installed in the library, and the contract work started in January 1913. By having the bindery inside the library, the turnaround time for binding a book (at Central and the branches) was a couple of days instead of a couple of weeks. Money saved in the first six months of the contract was over $1,000 (approximately $33,000 in today's economy) compared to what the library previously spent on binding. The Pacific Library Binding Company followed the library when it moved to the Metropolitan Building at the end of 1914. In 1923, the Pacific Library Binding Company moved into its longest-lived location at 770 E. Washington Blvd and continued to contract with the library on a yearly basis.

The library binder who thinks first of service and last of gain, and who measures what he does by the benefits he can bestow, is perhaps worthy of being considered a de facto staff member (of the library). Without doubt, the relations between binder and library are most satisfactory where some such attitude reciprocally exists.

—W. Elmo Reavis in Pacific Bindery Talk, April 1937

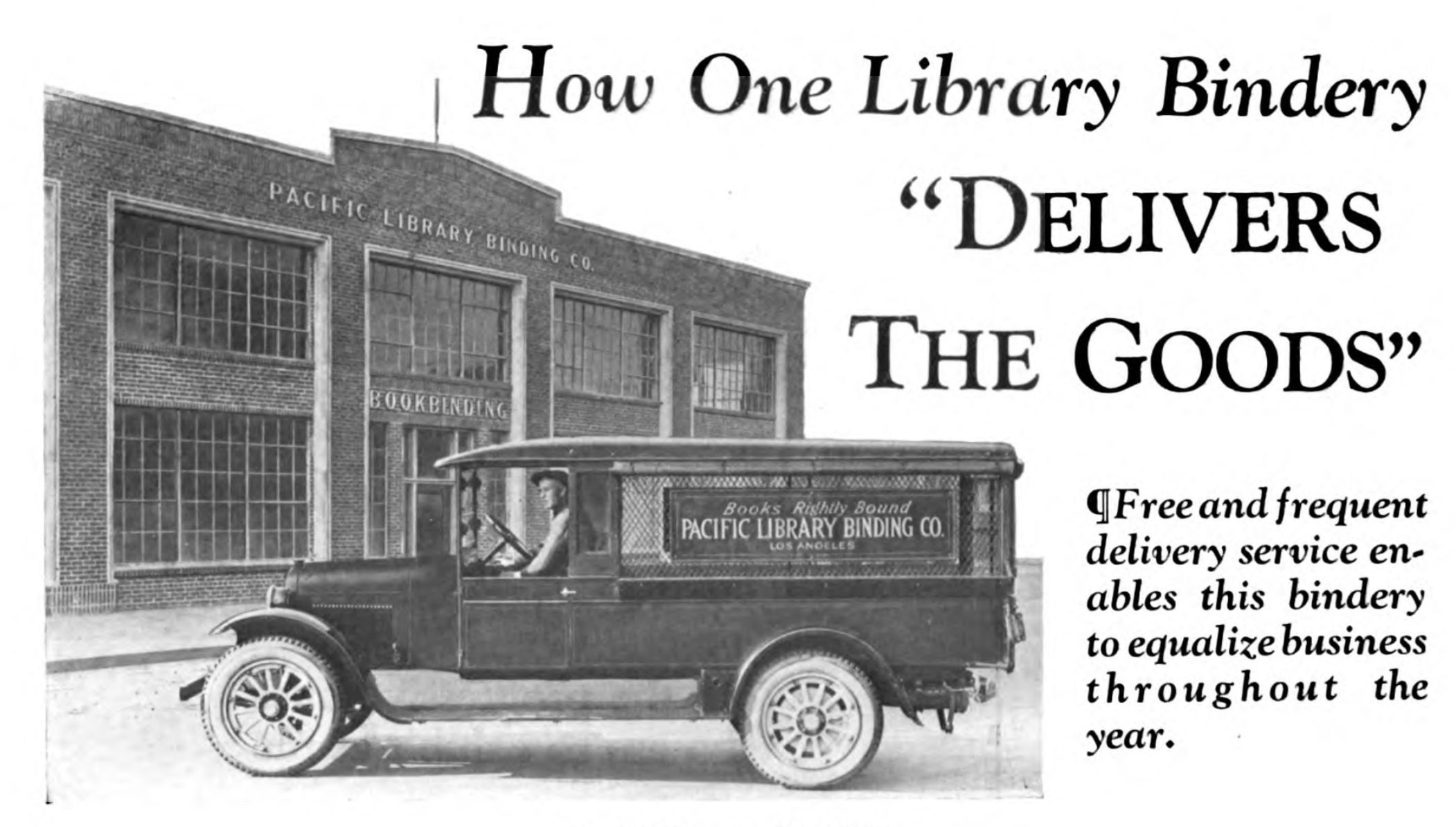

Reavis sought to know all of his customers personally and stressed respect, service, and quality in all of his dealings. For example, the Pacific Library Binding Company offered a 21-day turnaround, reasoning that if the book needed rebinding, it was because it was popular. [Other binderies could take months to rebind a book.] The bindery had its own trucks that would regularly pick up and deliver to Southern California libraries within a 100-mile radius of Los Angeles. A calendar was mailed to each customer showing the dates of upcoming routes, in addition to the routes within the city. At one time, there were eleven truck routes for the libraries outside the city of Los Angeles. Another perk the Pacific Library Binding Company featured was a service to replace missing magazine issues for libraries that sent them magazine binding jobs. At the request of Everett Perry, the Pacific Library Binding created the Sto-A-Way binding method for materials that should be kept but don't expect much handling (it was called a "storage binding" as opposed to a "service binding"). In 1928, Pacific Library Binding Company introduced new buckram and Fabrikoid (fabrics used in bookbinding) available in a variety of colors that their customers loved.

Let me ask you a question: Are we getting into Bindery Talk what you like to find there? Enough of shop talk?—or gossip? Or theory,—or practice? Are our articles too long, or what is there that you like or dislike about them? I should feel terribly upset if you complained about my binding—but I should not mind it at all if you find fault with my periodical. I think I know something about library binding; I know I know nothing about journalism! So send along your comments, they will help me have a Happy New Year, whatever you may say!

—W. Elmo Reavis asking for feedback on Pacific Bindery Talk, January 1936

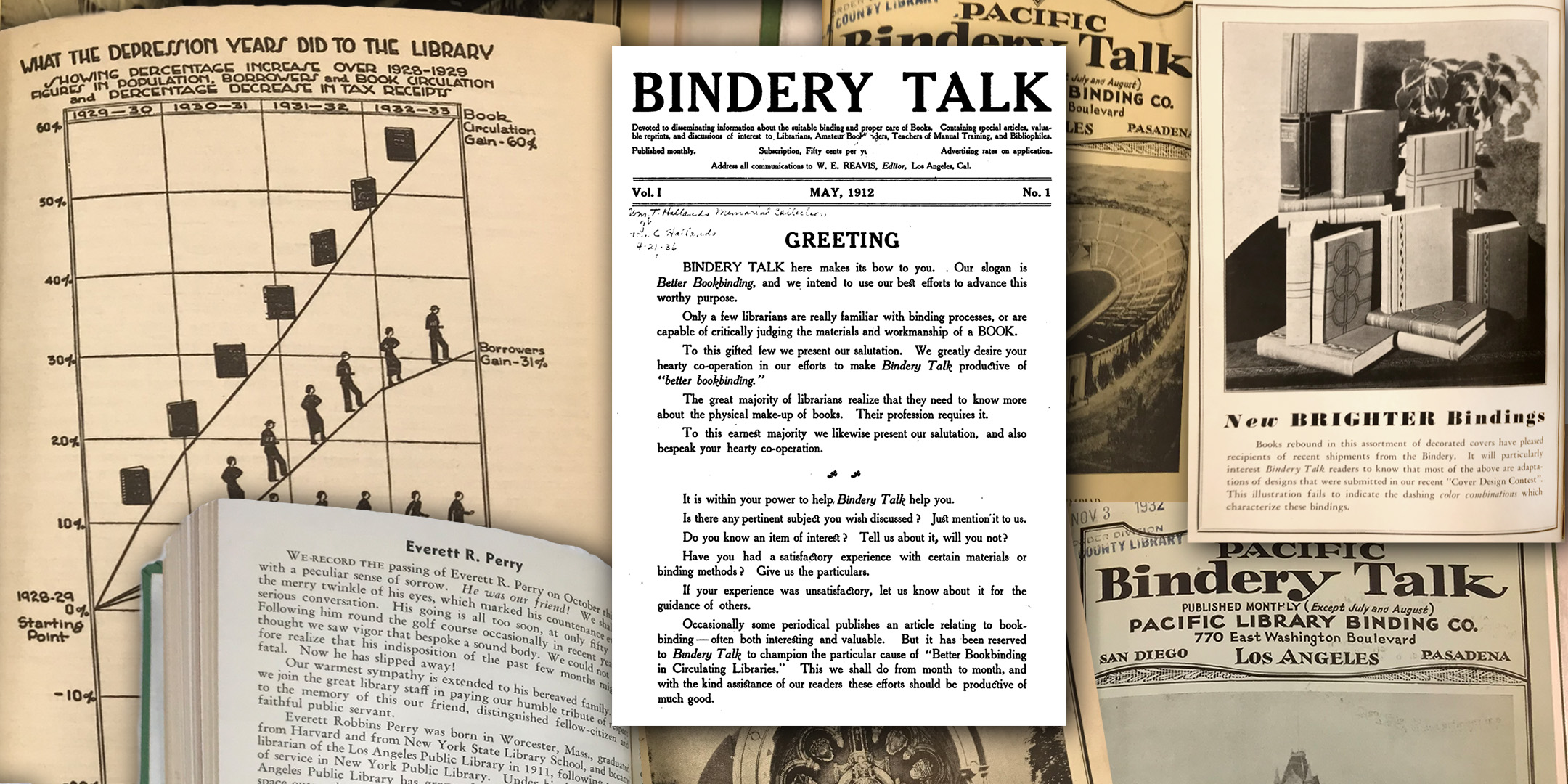

In May 1912, while still under the aegis of Commercial Printing House, W. Elmo Reavis launched his first issue of the bi-monthly publication Bindery Talk. The masthead explained the magazine's mission– to disseminate information about the suitable binding and proper care of books with articles and discussions of interest to librarians, amateur bookbinders, teachers of manual training, and bibliophiles. You can watch the Commercial Printing House transform into the Pacific Library Binding Company across its first four issues. The magazine was praised by the likes of Library Journal, but in search of more subscribers, it paused with the November-December 1913 issue. It was revived as the monthly publication Pacific Bindery Talk in March 1931 with increased contributors (under the editorship of T.R. Coles Jr., son of the secretary of the Pacific Library Binding Company) and lasted another ten years. The Los Angeles Public Library's publicist, Faith Holmes Hyers, was a frequent contributor to the later version of the magazine. In addition to a series of "Bookbinding for Librarians" articles, topics included the effects of the Depression on libraries and how to critique a poorly bound book. The magazine's coverage of the 1933 Long Beach earthquake and its effects on Southern California libraries is the most detailed narrative of the earthquake's effects on libraries that I've seen. There were also profiles of library workers in Bindery Talk and Pacific Bindery Talk, the first of whom was George Herzog. Mr. Herzog was in charge of the Los Angeles Public Library's bookbinding department and lectured on bookbinding and book repair at the library's training school.

"We try to give the students sufficiently wide laboratory treatment that we may drive home our points," stated Mr. Reavis. The book binding expert admitted that not all the books that the students will turn out will be models of artistic excellence but the student will make a book [while] learning something that as a prospective librarian she should know about binding and materials.

—"Embryo Librarians Learn Book Binding" Riverside [CA] Independent Enterprise, January 19, 1916

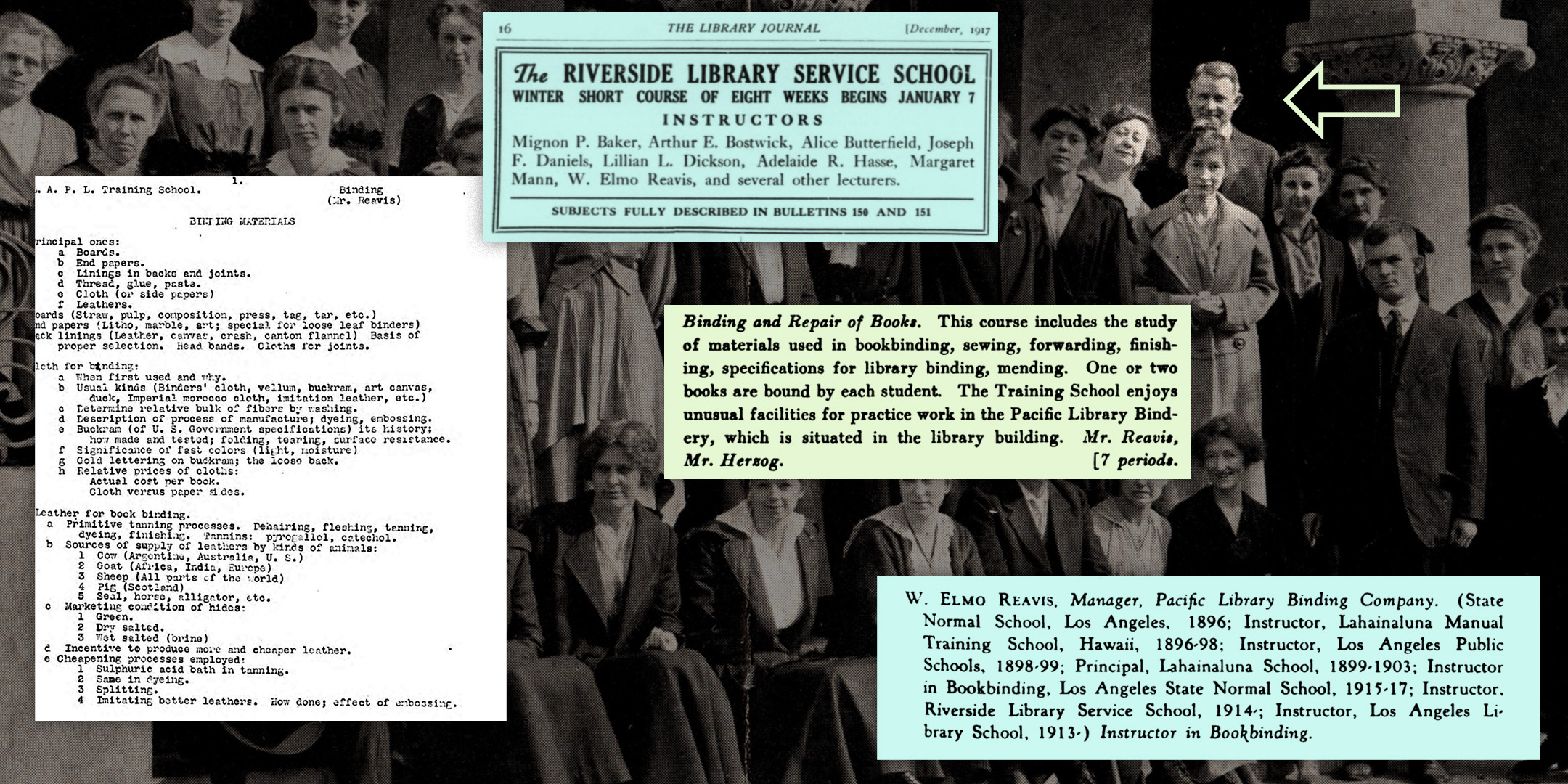

W. Elmo Reavis soon joined the ranks of lecturers at the Los Angeles Public Library Training School, the Riverside Library Service School, and the Los Angeles State Normal School. His bookbinding courses allowed for practical, hands-on binding working inside a bindery setting. His students were taught to bind two books of their choice, including one with pulpy, porous paper and one with firm, smooth paper. They were also taught to judge binding materials and learn "how to know a well bound book." For Everett Perry, having a bindery in-house was an excellent reason to try to elevate the Los Angeles Public Library Training Class into an American Library Association-accredited library school (which it did in July 1918). Reavis was praised for his experience and teaching ability by Los Angeles Public Library Training School staff and Dr. Charles C. Williamson in a report prepared for the Carnegie Corporation regarding Training for Library Work (1921). Reavis also shared his bookbinding lessons and experiences for the creation of the book A Course in Bookbinding for Vocational Training, published by the Employing Bookbinders of America in 1927. He spoke at conventions and conferences nationally and contributed to trade publications such as Bookbinding, Book Production, and The Inland Printer.

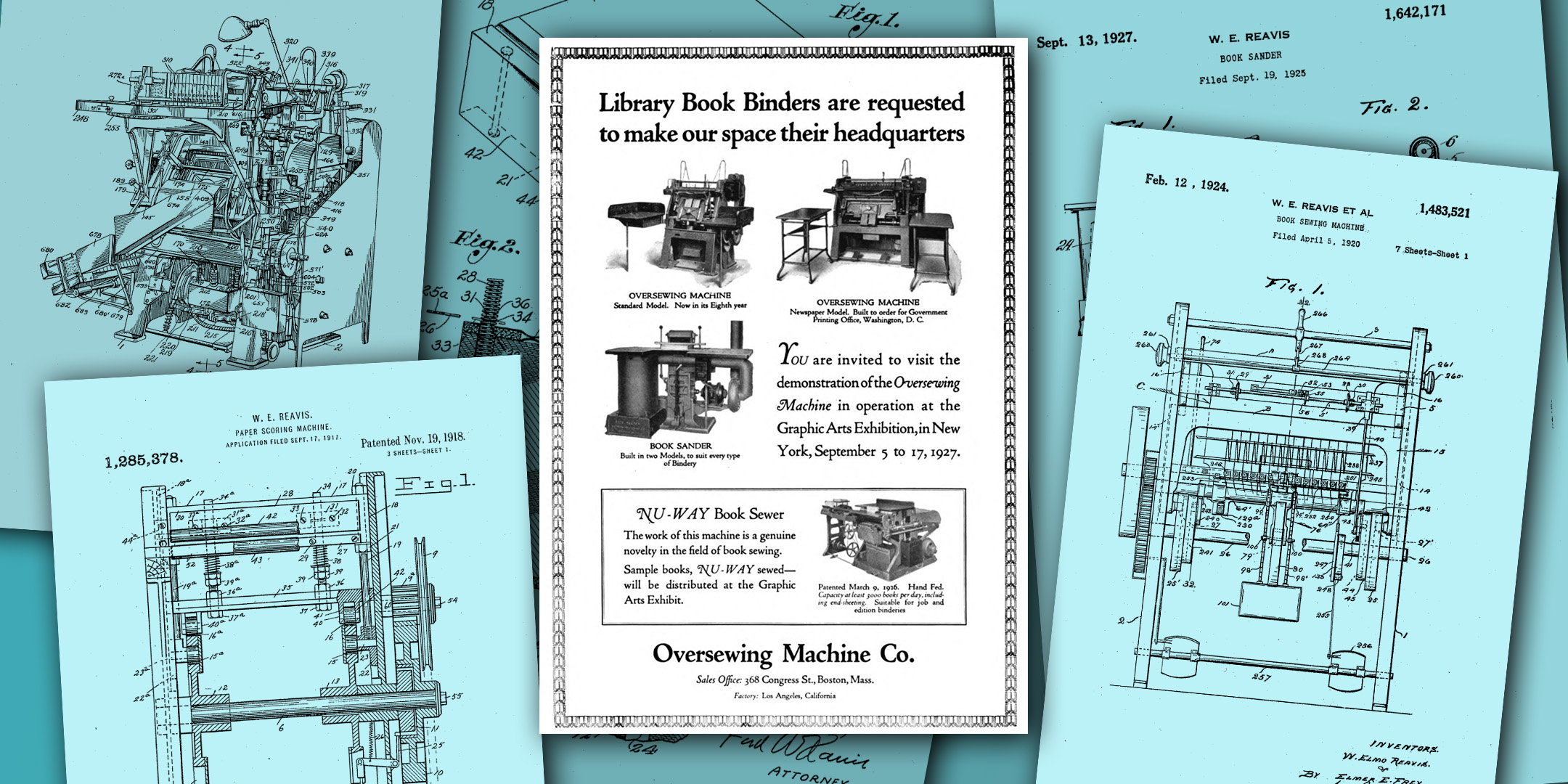

Mr. Reavis patented several pieces of bookbinding machinery that were used universally, most notably a book sewing machine manufactured by the Oversewing Machine Company, a company that he and Pacific Library Binding Company's secretary, T.R. Coles, organized to manufacture bookbinding machinery in 1918. He was an inventor of at least nine different machines and procedures dealing with bookbinding for the Pacific Library Binding Company and Oversewing Machine Company from 1917 to 1934. In 1936, he also invented an apparatus for making book covers for Picture Cover Bindings Inc. in Staten Island.

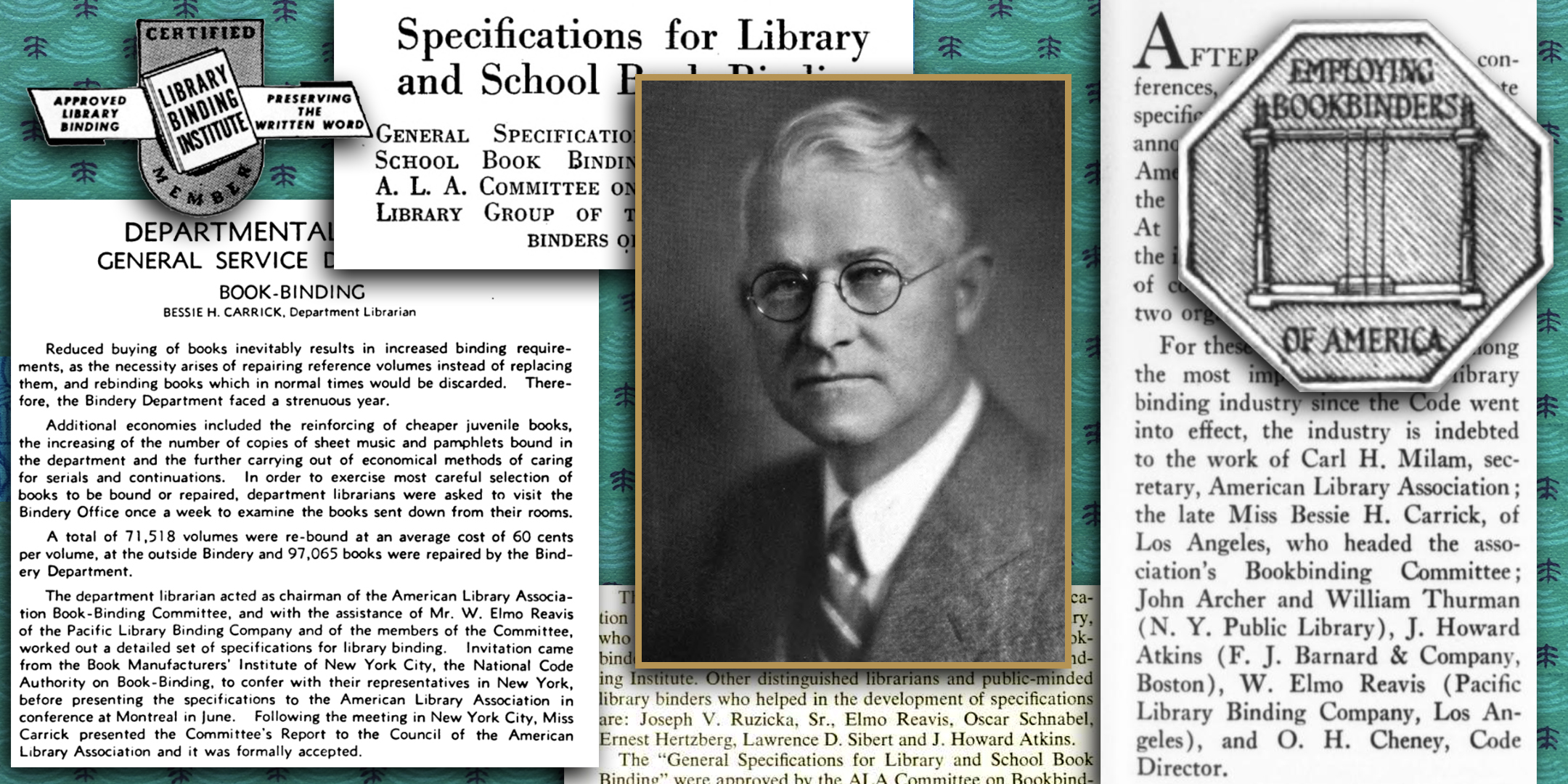

As a member of various trade organizations, Reavis fought for the standardization of library binding. In fact, he was part of the small group of librarians and library binders who helped develop the early library binding standards approved by the American Library Association and the Employing Bookbinders of America in 1923. [It should be noted that Bessie Carrick (1880-1934), longtime head of the Bindery Department at the Los Angeles Public Library, was also instrumental in the implementation of library binding standards.] Maurice Tauber's Library Binding Manual (1972) cites Reavis' perfection of the oversewing machine in 1920, and its timesaving properties, as ushering in what became known as the "library binding industry."

This is just the tip of the iceberg regarding the wonders of W. Elmo Reavis. His contributions to quality bookbinding for the California library community, his success in teaching California librarians and library workers the craft of binding, his dedication to the national standardization of library binding, the engineering of bookbinding machinery, and his establishment of a magazine focused on information of interest to California library workers, are just a few of the reasons to celebrate W. Elmo Reavis. Did I also mention that the Pacific Library Binding Company manufactured a branding iron to prevent the theft of library books across Southern California? That's a story for another day...

A hearty thank you to Ruth McCormick of the Riverside Public Library, and Raquel Borden, Dan Nishimoto, and Danielle Ball of the Los Angeles Public Library for their help researching this profile of W. Elmo Reavis.