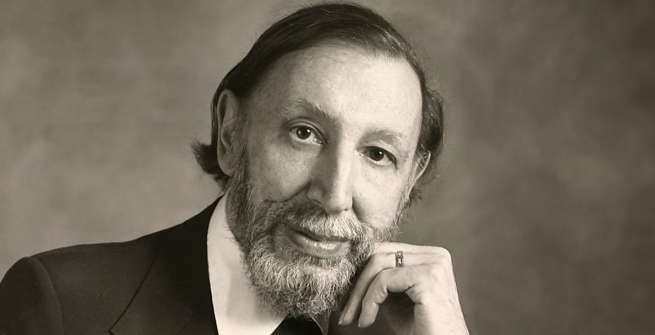

Alan Hovhaness (1911-2000) is probably the most prolific American composer of whom you have never heard. The composer's surviving oeuvre includes over 500 works: at least 67 symphonies, nine operas, two ballets, and about 100 chamber pieces. My brother Hovan, a chancel choir director, became a huge fan of the composer. Our home was filled with his music.

Hovhaness wrote his first composition at the age of four. His early influences were Mozart and Handel; later, Bartok and Sibelius. Jean Sibelius was the godfather of Hovhaness's daughter Jean, named after him. During his Armenian period (1943-1951), Hovhaness' musical foundation can be traced to the Armenian priest Komitas (1869-1935), who was undoubtedly his most esoteric influence. In fact, Hovhaness considered him the first minimalist composer.

Beginning in the mid-1950s and through the 1960s, he branched out, drawing inspiration from Medieval and early Baroque music, ragas from India, gagaku from Japan, and Korean percussion. You may be familiar with Symphony No. 2, Op. 132, Mysterious Mountain. With its strong mystic and meditative flavor, it is certainly his major breakthrough and probably his most famous work.

During much of his career, musical serialism and atonality were often in the forefront of art music, particularly the avant-garde movement. Hovhaness rejected musical trends. His music was criticised and jeered as being deeply old-fashioned. Yet, some see him as the forerunner of holy minimalism, new age, and the world music movement. His unique melodies are pure and straightforward. His recognizable style comes through in every piece.

For a sample of his music, consider one of his earlier works, Khrimian Hairig, Op. 49. Named for the head of the Armenian Church in the late 19th century, it is a short eight-minute piece for trumpet and strings. With just the right balance between longing, nostalgia, and hope for a new future, it has become our family favorite. My brother used the third arc (at the 5:30 mark) as the bridal march for his wedding; I was compelled to use it at his funeral service… Hinako Fujihara Hovhaness, the composer's widow, called it "noble and heroic," a piece she considered his self-portrait. She named it "his true masterpiece."