It’s 2026, and here at the Library, we’re looking forward to commemorating 100 years of the Central Library. Dedicated in July 1926, the opening of this architectural icon was a milestone not only for the Library system but for the entire city. It was such an important moment that we’ve decided to celebrate all year long. We hope you’ll join us!

While the opening of the Central Library was truly momentous, it was far from the only exciting thing happening in Los Angeles in 1926. The city was, to put it mildly, booming. So, to kick off our yearlong celebration, let’s take a brief look back at 1920s Los Angeles to see what our fellow Angelenos were up to a century ago.

During the 1920s, Los Angeles was transforming from a backwater town into a world-famous metropolis. At the turn of the century, the community was concentrated around downtown, surrounded by sparsely populated areas filled with citrus groves and oil fields. L.A. barely cracked the top ten list of the most populated U.S. cities. By 1915, Hollywood had become the epicenter of the film industry, but few other major industries existed at the time.

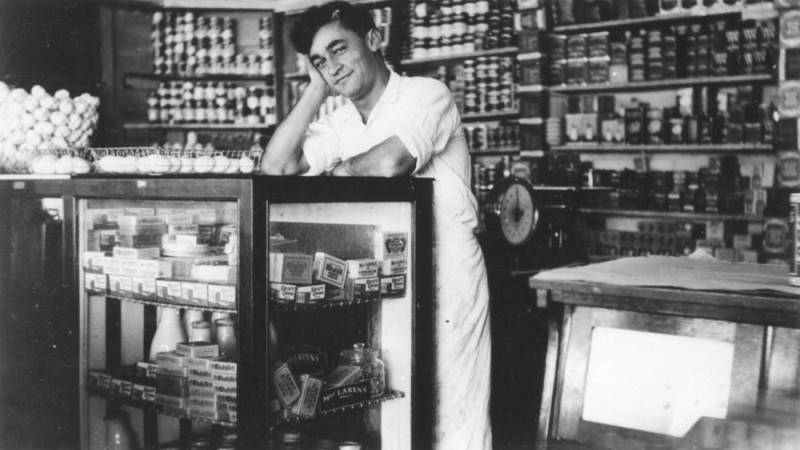

For years, Angelenos carried something of an inferiority complex when comparing their young city to established powerhouses such as New York, Boston, and Chicago. A concerted effort by business leaders sought to change that. City boosters marketed the region's climate and natural environment as ideal for eastern manufacturers to set up shop. Companies like Firestone and Goodyear opened plants, and soon L.A. became the world's second-largest center of tire production.

Major oil discoveries in the area led to the petroleum industry surpassing agriculture as California’s leading industry by the mid-1920s. The county was now producing one-quarter of the world’s petroleum. Propelled by the petroleum trade, the Port of Los Angeles overtook San Francisco as the busiest seaport on the West Coast.

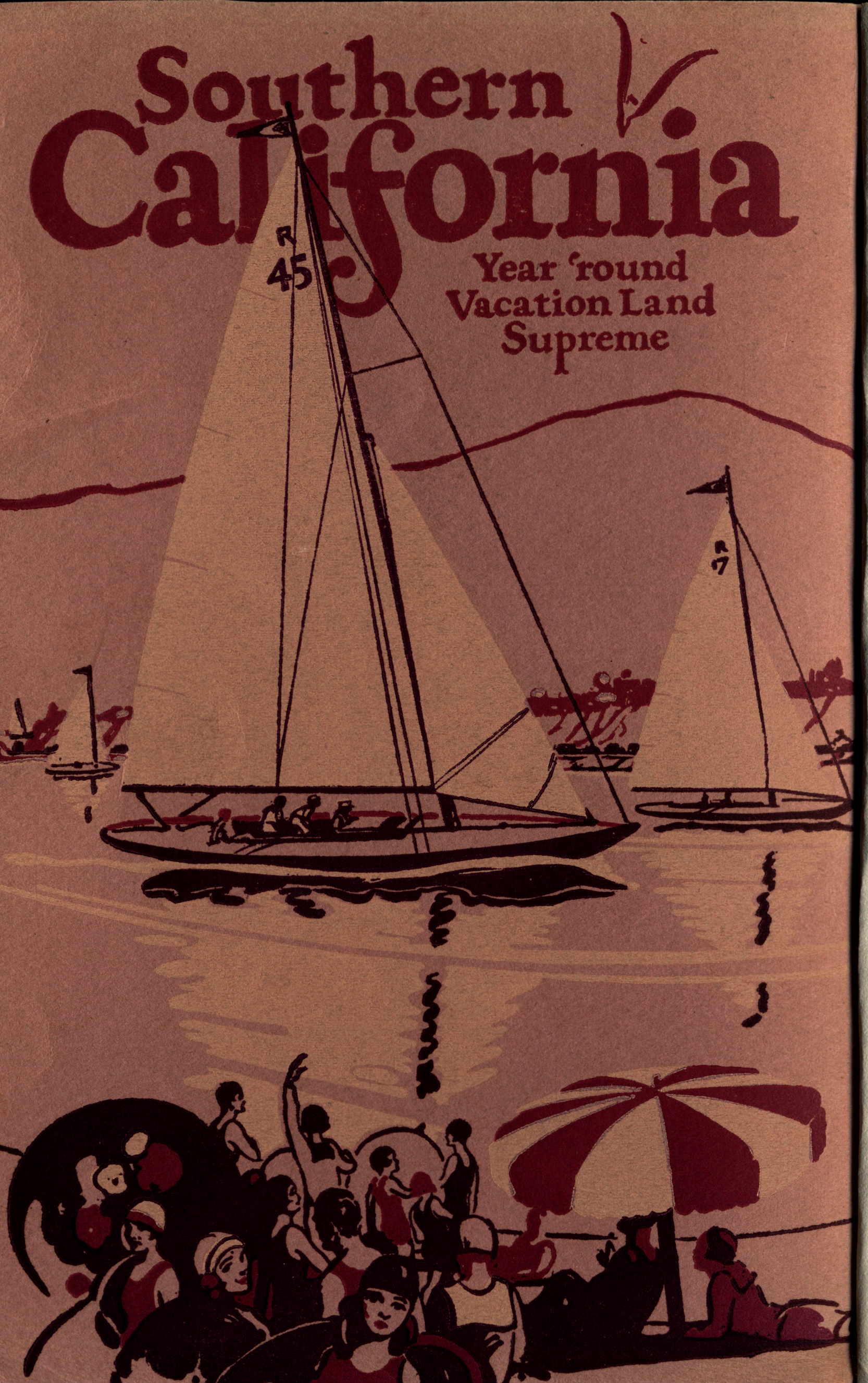

If Los Angeles was being marketed as a place to work, it was equally promoted as a place to play. Powerful businessmen such as Los Angeles Times publisher Harry Chandler formed the All-Year Club of Southern California, spending millions to promote the region as a year-round vacationland. Their efforts worked. By 1930, tourism and conventions accounted for 10 percent of the city’s economy.

Visitors arrived by train, ship, or the newly completed U.S. Route 66, with its western terminus in downtown. Commercial passenger flights weren’t yet a thing, but determined travelers might hitch a ride with a mail carrier to one of several small private airfields. (Mines Field, later LAX, would not open until 1928.) Visitors could stay at any number of new hotels—the Ambassador, the Biltmore, the Cecil, the Mayfair, or the Hollywood Roosevelt, site of the first Academy Awards in 1929. The new Hotel Figueroa made history as the first U.S. hotel with a female manager, offering women travelers a safe and independent place to stay.

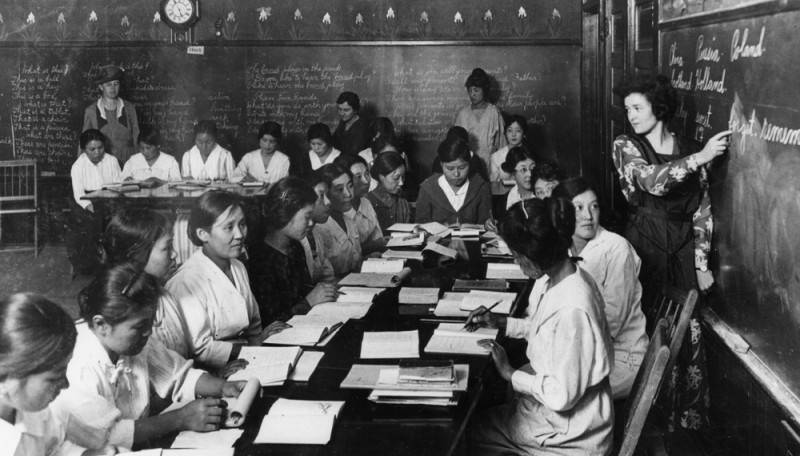

Fueled by these industries and the general prosperity of the decade, Los Angeles became a major economic hub. Drawn by jobs and the lure of Hollywood, which by then produced 90 percent of major films, people poured into Southern California. In 1920, Los Angeles surpassed San Francisco in population for the first time. By the decade’s end, the population had doubled to 1.24 million. Many newcomers were transplants from the Midwest and South, while others immigrated from Mexico and abroad. Though still predominantly white, Los Angeles was growing increasingly diverse, home to vibrant Mexican, Japanese, Chinese, Italian, Armenian, and Jewish communities.

The population spread outward from downtown to the San Fernando Valley and southward to San Pedro. The city’s footprint expanded as it continued to annex smaller communities, such as Watts, Sunland, and Green Meadows. Outside the city limits, distinct working-class communities such as South Gate formed.

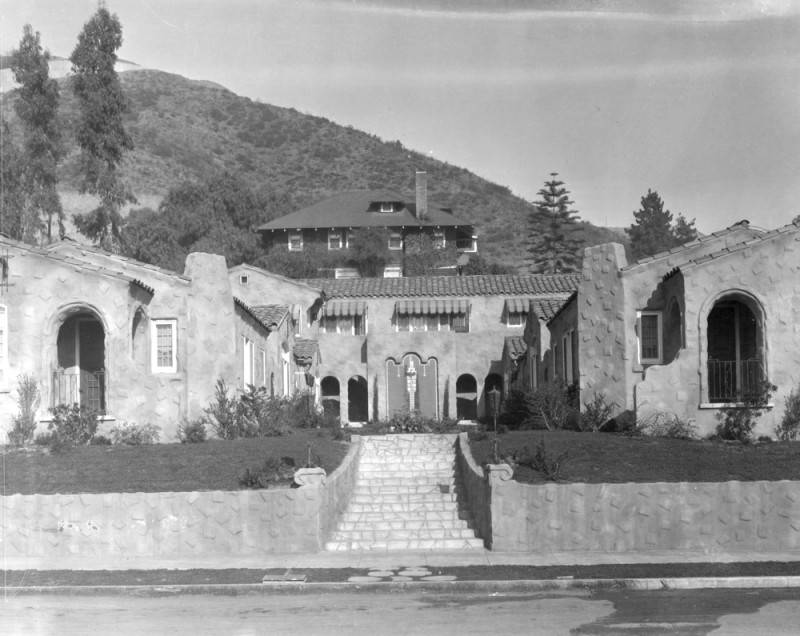

With the population growth, the housing and real estate boom was inevitable. Revival styles, like Mediterranean, Spanish, and Tudor, dominated, especially in more upscale areas. Smaller apartment buildings gave way to expansive tower apartments. These buildings served as a great landing place for the “floating” population of long-term tourists, who made up about ten percent of the city’s population at any given time. The city also embraced distinctive housing types such as bungalow courts and fourplexes, accommodating both middle- and working-class residents.

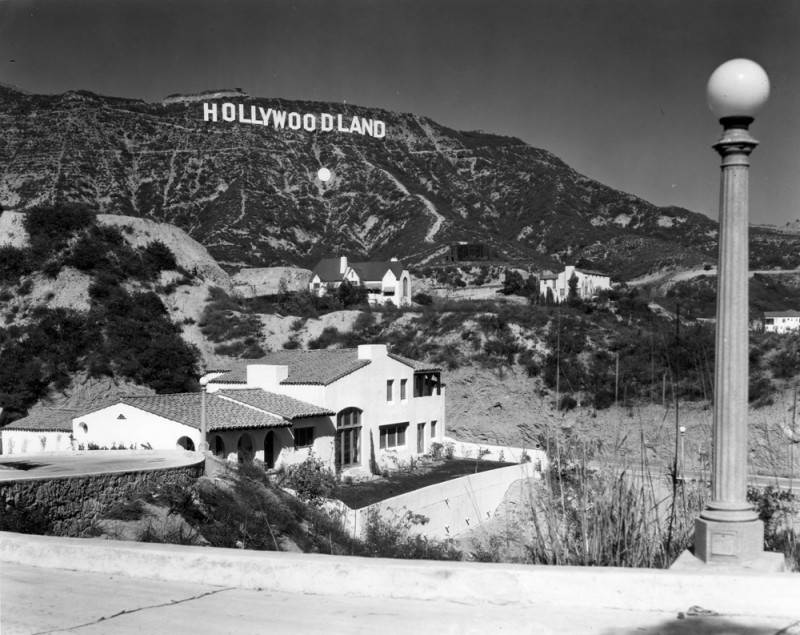

Planned neighborhoods like Leimert Park, Hollywoodland, and Hancock Park sprang up. By mid-decade, about half of the housing stock consisted of single-family homes, which were largely owner-occupied. This was a distinct departure from other American cities, where most residents were renters.

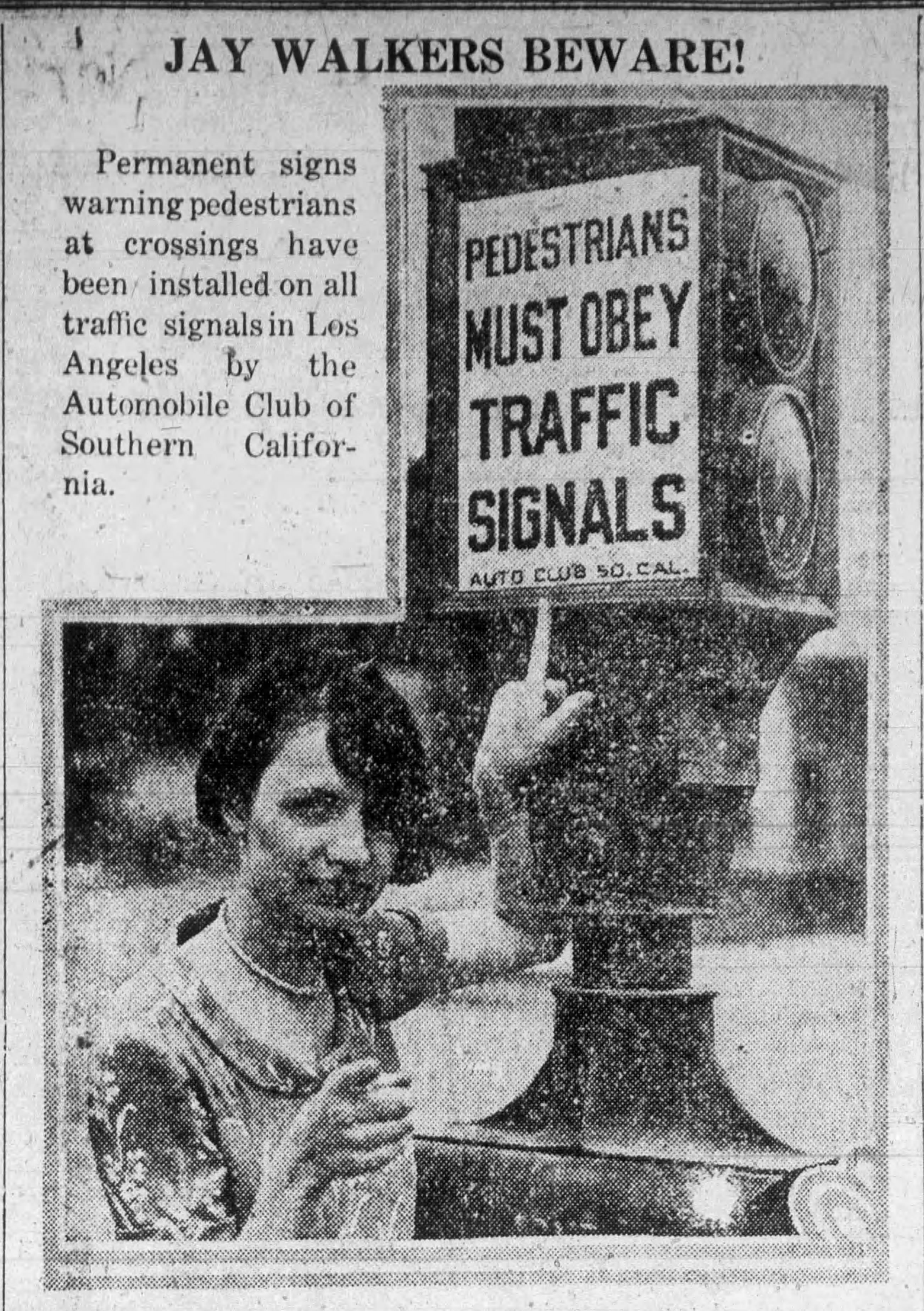

This massive expansion gave birth to the urban sprawl we know today, made possible by the rise of the automobile. Los Angeles was truly the first car-centric city. By 1925, there was one car for every three residents, twice the national average. Streetcars still dominated public transit, with the Los Angeles Railway’s “yellow cars” and Pacific Electric’s “big red cars” at peak ridership in the mid-1920s. Between public transportation and their own cars, Angelenos could live farther from work than ever before. Yet the convergence of streetcars, motorists, and pedestrians meant traffic conditions were out of control. Los Angeles even “boasted” the world’s busiest intersection, at 7th & Broadway.

Instead of investing in underground tunnels and raised rails, L.A. went all in on prioritizing cars. In 1925, the first traffic ordinance was passed. Influenced largely by the automobile clubs, the new rules were a huge win for motorists. Pedestrians were the big losers. Suddenly, a new type of criminal— the jaywalker—was created. L.A.’s traffic ordinance became a template for cities across the country.

As the car culture emerged, the automobile became not just a means of transportation, but an integral part of leisure time. One example was the Elysian Park auto camp, which opened in 1920 at the behest of the Auto Club of Southern California. The public facility offered folks an outdoor camping experience easily accessible by car, and it was an attractive alternative to hotels for budget-minded tourists.

Angelenos had a number of outdoor activities at their fingertips. The climate and natural environment marketed by city boosters were theirs to enjoy year-round. In 1925, the creation of the Departments of Parks and Playgrounds and Recreation focused more on recreation for people of all ages. Clubhouses and swimming pools were built, and folks enjoyed activities such as golf, horseshoe pitching, and picnicking. Westlake Park (now MacArthur Park) was filled with boaters, Pershing Square was a lush downtown oasis, and the Municipal Plunge in Griffith Park was one of the largest swimming pools of the time.

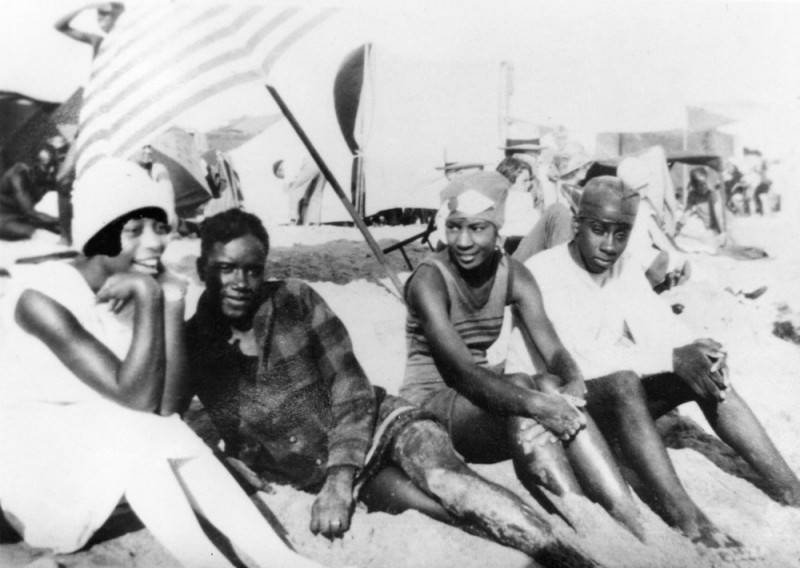

In 1928, the city dredged sand to create Cabrillo Beach in San Pedro, and recently annexed Venice was another popular spot for beach goers. As with housing, segregation—both legal and informal—heavily shaped where Angelenos could recreate. The beach at Bay Street in Santa Monica was a popular spot for African Americans during the Jim Crow era. Dubbed “The Inkwell” in a derogatory manner, the name was adopted as a badge of honor by the Black community.

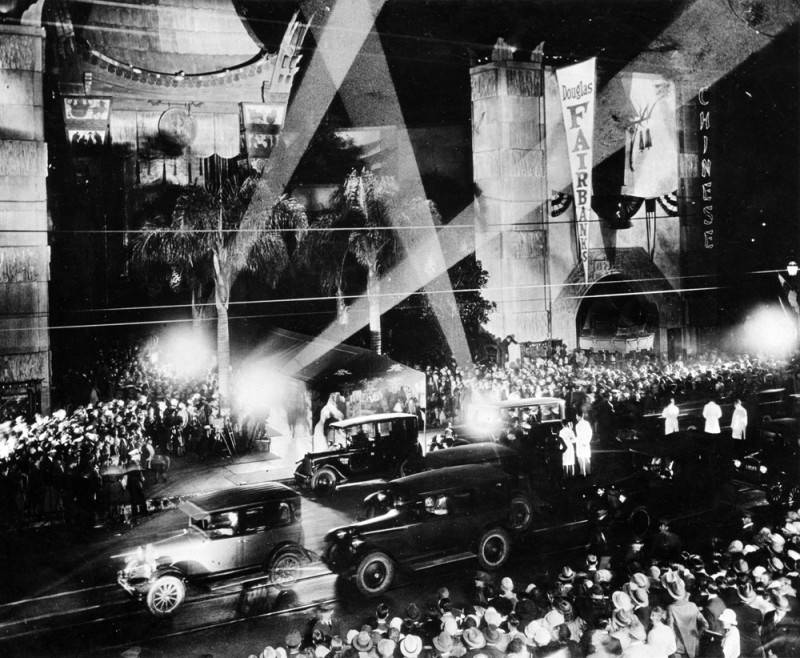

The decade also brought a boom in entertainment. The masses loved going to the movies, and the city had dozens of theaters, largely concentrated in the downtown Broadway Theater District. The Tower Theater, built in 1927, was the first theater wired for “talkies” and was the location of the West Coast premiere of the revolutionary sound film The Jazz Singer. Lots of new live and movie venues opened during the era, including Loew's State Theatre (1921), Grauman's Egyptian Theatre (1922), The Vista (1923), El Capitan Theatre (1926), Westlake Theater (1926), and Grauman's Chinese Theatre (1927). The fourth and final iteration of the vaudeville Orpheum Theater opened on Broadway in early 1926. Meanwhile, the Hollywood Bowl and the Los Angeles Grand Opera emerged as cultural institutions.

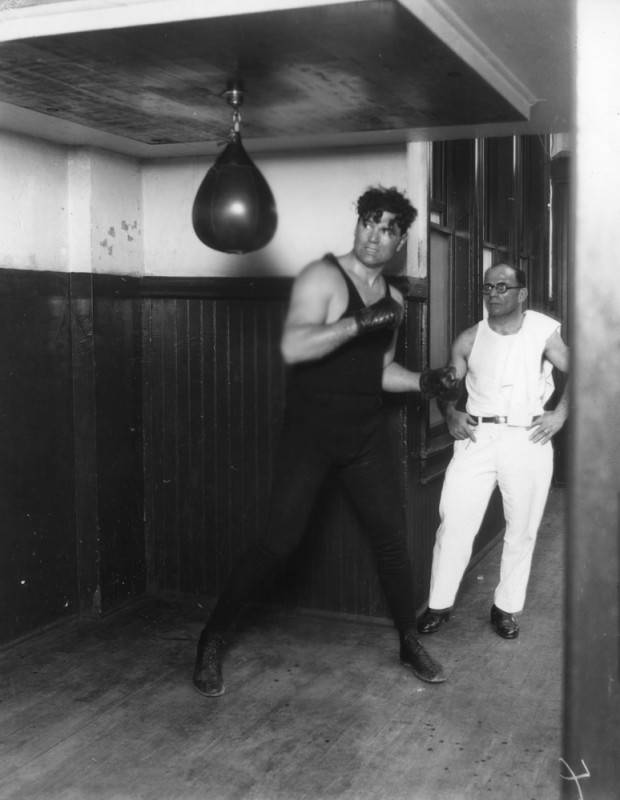

The 1920s were the Golden Age of sports, and Los Angeles joined the excitement. USC football became a national powerhouse, drawing huge crowds to the new Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. In baseball, the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League played at Wrigley Field—built in 1926 by chewing-gum magnate William Wrigley Jr., who gave his Chicago ballpark the same name one year later. Boxing was also one of L.A.’s most popular spectator sports, with matches being held almost every night. Venues like the Hollywood Legion Stadium and Grand Olympic Auditorium drew enormous crowds, including many celebrities. (Despite this rich sports culture, L.A. wouldn’t get its first professional franchise until the Cleveland Rams football team’s arrival in 1946.)

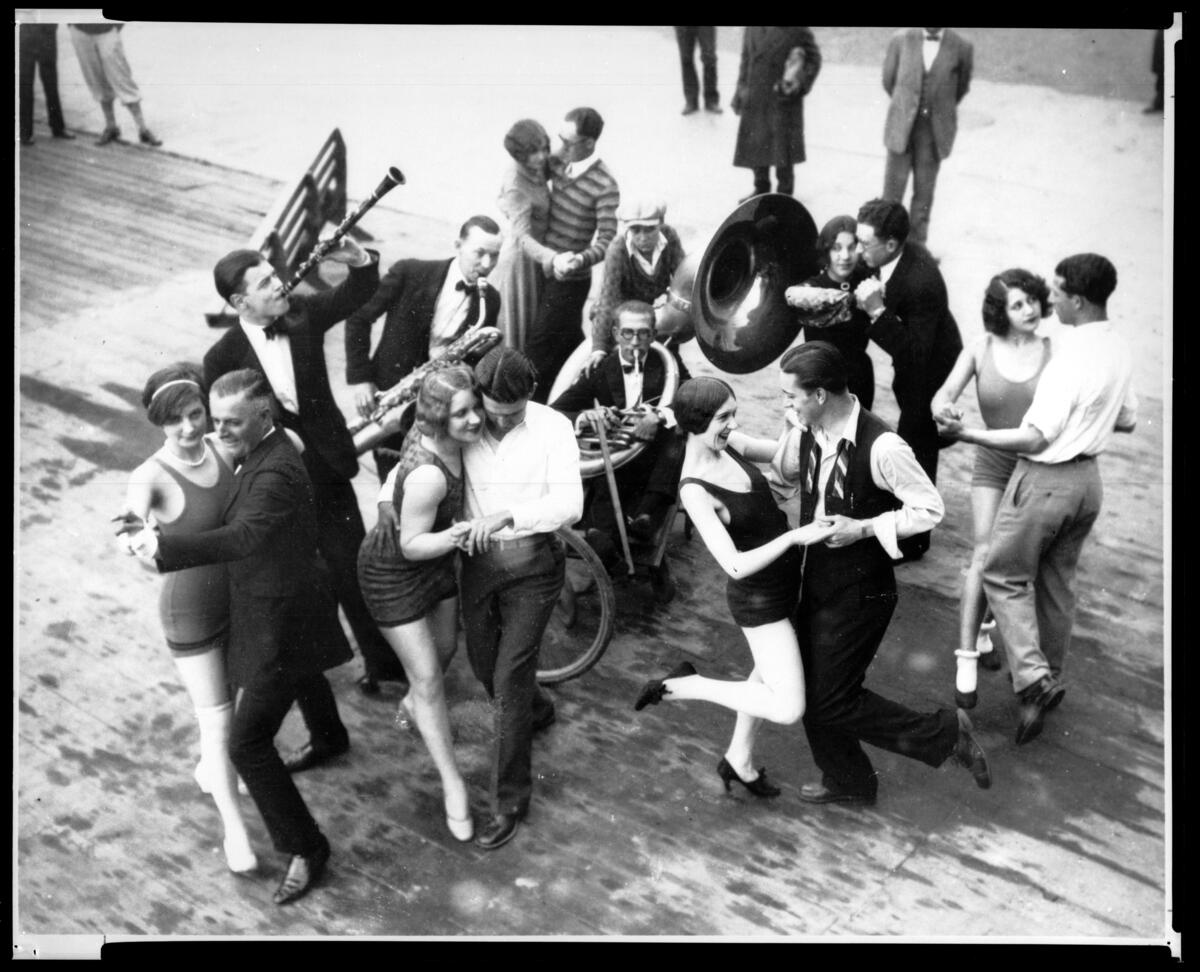

Nightlife in Los Angeles was a lively affair during the Roaring Twenties. In 1921, the grand Ambassador Hotel opened its doors, drawing crowds to its tropical-themed Cocoanut Grove club. The lavish venue that could seat up to a thousand guests and featured imitation palm trees salvaged from Rudolph Valentino’s hit film The Sheik. Film stars and Angelenos about town mingled there, enjoying fine dining, live music, and the latest dance crazes sweeping the nation.

Dance halls flourished across Los Angeles, offering places for people to let loose, though not all cities were as permissive. Pasadena banned dancing after 10 p.m., while Long Beach outlawed “suggestive” cheek-to-cheek moves. Los Angeles city was less regulated, but in April 1927, one particularly spirited marathon dance was raided by police at the urging of the city health director, who ordered dancers pulled from the floor after an exhausting twenty hours of continuous movement.

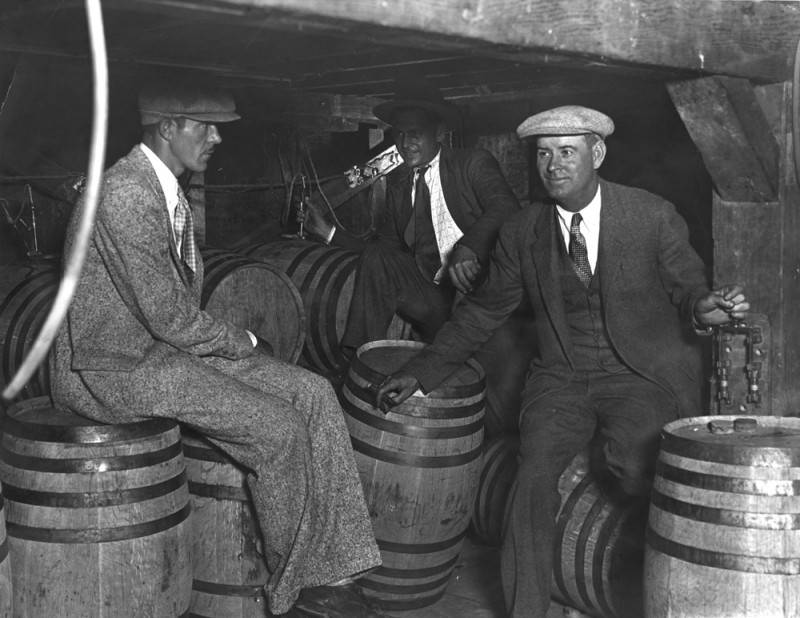

Prohibition was in full effect, but Angelenos didn’t let that dampen the mood. It’s estimated that L.A. had twice as many speakeasies as there had been bars before Prohibition was enacted. Many of these establishments were located Downtown, where bootleggers made use of existing tunnels to move and store their product. The rampant political corruption in the city allowed this underground industry to flourish.

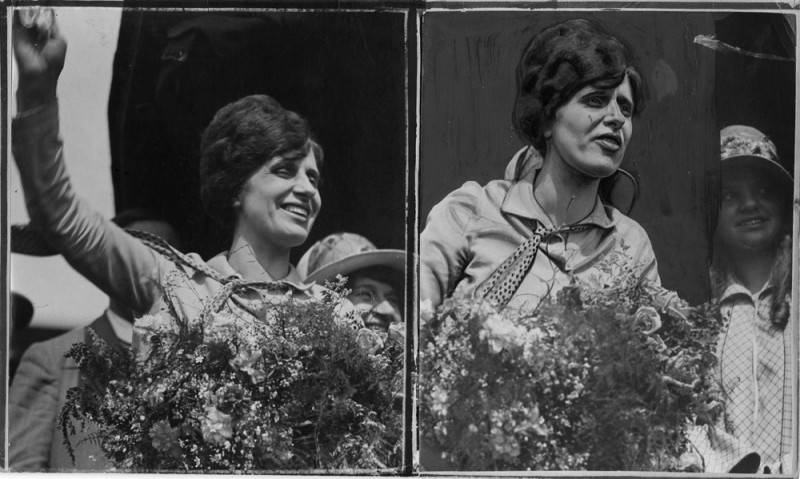

Amid the glamour and excess, spiritual movements also flourished. Southern California had long been a haven for unconventional faiths, and 1920s Los Angeles teemed with revivalist preachers, mystics, and spiritual seekers. John Steven McGroarty of the Los Angeles Times observed that the city "is a breeding place and rendezvous of freak religions" due to its inviting climate. Prominent citizens dabbled in the occult, while many folks were exposed to spiritual paths like Hinduism and Buddhism for the first time. Asian philosophy was at the height of popularity, exemplified by figures such as Paramahansa Yogananda, who founded the Self-Realization Fellowship in Mount Washington and greatly influenced the American yoga movement. The era featured fundamentalism mixed with Pentecostal fervor, characterized by media savvy religious leaders like "Fighting Bob" Shuler and Aimee Semple McPherson. This religious landscape helped form the city’s distinctive multicultural identity.

When the Central Library opened in 1926, it wasn’t just a resource for readers. It was a signal that Los Angeles had arrived as a major city on the world stage. L.A. was fast-growing, culturally vibrant, and economically booming. But it was also a city affected by political corruption, segregation, and rapid—often chaotic—expansion. Like Los Angeles itself, Central Library has faced growing pains, yet always emerged stronger.

In his 1926 essay "Los Angeles, a Miracle City," writer and publisher Edgar Lloyd Hampton marveled at the city’s meteoric rise, its booming industries, abundant resources, and magnificent scenery and climate. He concluded with a sentiment that still resonates a century later:

"Yet the things the people of Los Angeles have already done are only a prophecy of the things they are about to do."

Here’s to another 100 years, Los Angeles!