The Looking at Art - In the Street program series celebrates artists and art historians who create and preserve open space street art in Los Angeles.

90 years ago, on October 9, 1932, the Los Angeles Times ran a story announcing, "Great Art Work To Be Unveiled: Ceremony for Siqueiros's Fresco Scheduled for Tonight." The article stated that "David Alfaro Siqueiros, famed Mexican artist whose works have gained worldwide acclaim, will unveil his most recent creation, 'Tropical America,' at Plaza Art Center on Olvera Street tonight. The work is a colossal fresco portraying the past of the Americans." As this article makes apparent, even before Los Angeles had seen Siqueiros' new mural, entitled América Tropical, by the artist, it was assumed to be a monumental and important work for the City. In April 1932, when he arrived in Los Angeles, David Alfaro Siqueiros was already world-famous. He was one of a trio of artists who had created an international stir after the Mexican Revolution (the other two were Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco—in 1932, the term 'Los Tres Grandes' was coined to describe them). Although their styles were different, each had been creating large-scale public works which revitalized contemporary mural-making. Given the legendary status, Siqueiros possessed in the early 1930s, and the excited anticipation Los Angeles felt at the prospect of his largest public mural, why, just a few years later, was América Tropical; whitewashed in an attempt to erase it from Los Angeles history?

Olvera Street

Part of the answer lies in the deliberate clash between an artist and a place. América Tropical was sited on Olvera Street, and in 1932 when Siqueiros arrived in Los Angeles, Olvera Street was two years into its most recent incarnation as a prominent tourist destination. One of the oldest streets in Los Angeles, it had bordered the city's central plaza since at least the 1820s, when the Plaza de Los Angeles was relocated to its present location after the Los Angeles river flooded. Later in the 19th Century, the street was home to powerful and wealthy residents, including Governor Pío Pico and Agustín Olvera, the judge the street was named in 1877. It was also filled with different immigrant communities, including residents of Chinese, French, Italian, and Mexican heritage. By the 1920s, the adobes of Olvera and Pico had been demolished, and the street itself had become neglected.

Olvera Street would now enter its next era through the efforts of Christine Sterling. After the death of her husband, she took an interest in historic Los Angeles and began a campaign to preserve the remaining historic structures surrounding the Plaza. She managed to stop the City's demolition of the Ávila Adobe when it was condemned and obtained a lease on the property. She then started an intense fundraising campaign to repair it and alter the entire historic Plaza area. She eventually gained the support of Harry Chandler, the owner of the Los Angeles Times, and other prominent civic leaders.

From the start of her fundraising efforts, she linked the history of Olvera Street and the Plaza to a romanticized, nostalgic version of Los Angeles' Spanish and Mexican past. In a Los Angeles Times article from December 18, 1928, she was listed as sponsoring an "old fashioned, colorful Spanish serenade" at the Ávila Adobe and stated, "If the city will permit me, I intend to take over the entire little street on which the historic adobe stands and convert it into a beautiful, sanitary Mexican market." In another article on May 26, 1929, the entire area was described as being planned as "A Mexican Street of Yesterday in a City of Today," and it was stated that Mrs. Christine Sterling hoped to "...give Angelenos and visitors to the predestined Latin-American trade capital a glance backward to the days when voices lingered lovingly here on the vowel sounds, and all was dance and sunburned mirth in the evening by the patio fountains."

This latest incarnation of Olvera Street opened on Easter Sunday in 1930. A City ordinance permanently closed the street to vehicular traffic, and it became the site of restored historic buildings, shops, vendor's stalls, and restaurants. All the businesses fit the romantic, folkloric theme. It was an immediate tourist success. Just two years later, in 1932, when Siqueiros arrived, it was also an official Olympic venue for the Los Angeles hosted games.

As carefully managed as the image of Olvera Street became after 1930, the Plaza itself was still a place of gatherings such as political rallies. It was also in the early 1930s sometimes the site of deportation sweeps. In the United States, after the economy crashed in 1929, Mexicans and Mexican-Americans endured years of intimidation, brutality, and forced deportation by federal and local authorities. One of the most infamous Plaza raids occurred on February 26, 1931. On this afternoon, the LAPD sent units to the Plaza, where they sealed off the streets, and federal officials questioned everyone there on their immigration status (estimated to be about 400 people). 18 people were arrested for deportation.

A year and a half later, this place with its complicated history (a history that the current Olvera Street image mostly tried to ignore), and situated in the heart of Los Angeles, was where Siqueiros was hired to create a large-scale mural.

Siqueiros in Los Angeles

Arriving in Los Angeles in April of 1932, Siqueiros stayed just seven months in Los Angeles but managed (with the assistance of a group of artists, many of whom he taught at the Chouinard Art Institute) to create three outdoor murals. The first, Mitin Obrero (Workers Meeting or Street Meeting), grew out of the class he taught at Chouinard. The second mural, Portrait of Mexico Today, was created for film director Dudley Murphy and was the only work not visible to the public (this is also the only Siqueiros mural in the United States which was never whitewashed or destroyed, and it can be now seen at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art). The third was América Tropical. All three were political artworks, but América Tropical was the largest mural (18 by 82 feet) and was in the most prominent location. It was this mural that would have the most significant impact on Los Angeles' history, both in its own right as an artwork and because of the reactions it provoked.

Even before he arrived in the United States, Siqueiros had a reputation for being the most politically uncompromising and sometimes militant of Los Tres Grandes. Born in 1896, he studied art but then fought as a soldier (achieving the rank of army captain) in the Mexican Revolution. After traveling to Europe as a military attaché (but where he was also able to visit many museums and galleries), he returned to Mexico in 1922, and he, along with Rivera and Orozco, began to create murals for President Álvaro Obregon's government in prominent civic and educational locations. Their murals depicted social and political subjects while attempting to connect to as many viewers as possible. They often experimented with pre-Hispanic Mexican imagery and innovative mural and fresco techniques. They were credited with reviving murals as a relevant contemporary art form and were considered some of the most exciting artists working in the world.

Being very politically active, a Communist, and a union organizer, Siqueiros later ran afoul of the government when it outlawed the Communist Party and was jailed in 1930. In 1931 he was put under house arrest in Taxco and eventually exiled from Mexico in 1932. He and his wife, Blanca Luz, then decided to travel to Los Angeles.

After finishing Mitin Obrero at Chouinard, Siqueiros was approached by F.K. Ferenz to create a mural for the 18 by the 82-foot outer wall on the second story of the Italian Hall on Olvera Street. This was a very central location, and passers-by could also see part of the mural on the street below. This site must have been intensely appealing to Siqueiros for many reasons, including its visibility.

Ferenz, affiliated with Christine Sterling, told Siqueiros that the mural's theme should be tropical America to fit with Olvera Street's current atmosphere. Siqueiros agreed to use this title and theme. According to Siqueiros, the Olvera Street leaders wanted a mural filled with "happy men, surrounded by palms and parrots where fruit voluntarily detached itself to fall into the mouths of the happy mortals." Then for the next two months, he set about designing and painting the mural with the assistance of about 20 to 30 other artists he called the "Bloc of Mural Painters" (these included Dean Cornwell, the painter of Central Library's rotunda murals, Jackson Pollock's half-brother Sanford McCoy, Harold Lehman who became a member of California's post-surrealist movement, and Wiard "Bill" Ihnen a cinematic art director for such films as Blonde Venus and Duck Soup).

While most of the mural was visible to the public or viewers, such as Christine Sterling, Siqueiros managed to keep the central figure of the mural-covered during the day and worked on it at night. It was unclear before its unveiling what exactly the artwork would depict. On August 24, Arthur Millier in the Los Angeles Times said that the new mural would depict a "ruined Indian temple" and also "huge trees in which parrots would lodge."

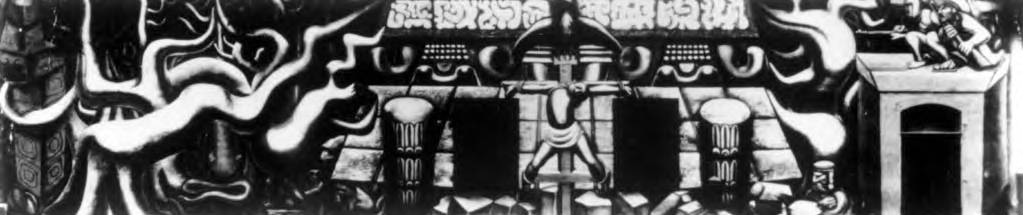

When it was revealed at its dedication ceremony on October 9, viewers did see a ruined pre-Colombian temple, but it was in the midst of an ominous jungle. On the right, two men crouched on a rooftop carrying guns. An indigenous farm worker was crucified on a double-cross in the mural's center. Above the cross perched an eagle painted to deliberately evoke the eagle on United States money. It was not only the opposite of a lush conception of "tropical America " but, with the eagle's inclusion, implicated the United States in imperialist violence being perpetrated in the Americas. Siqueiros was aware of injustices in Mexico and Latin America and the deportations, racism, and mistreatment experienced by Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in the United States and in the Plaza de Los Angeles itself. The América Tropical Interpretive Center includes this quote of his from 1933: "We had been requested to paint Tropical America, and we could not lie by painting a false Tropical America; we had to paint the true, authentic Tropical America."

After its dedication, Arthur Millier posted a glowing, but confused, review of the mural in the L.A. Times on October 16. He began by titling the mural "Tropical Mexico" and equated the crucified figure with Mexico's "history" of human sacrifice. For Millier, it was "a Mexican's picture of his troubled land." There is no mention of how civic leaders such as Christine Sterling felt about the mural at its unveiling. Still, presumably, given how quickly it was whitewashed, they were extraordinarily unhappy with it. Siqueiros had created an artwork designed to stand in opposition to Olvera Street's iconography and placed it in the heart of Olvera Street.

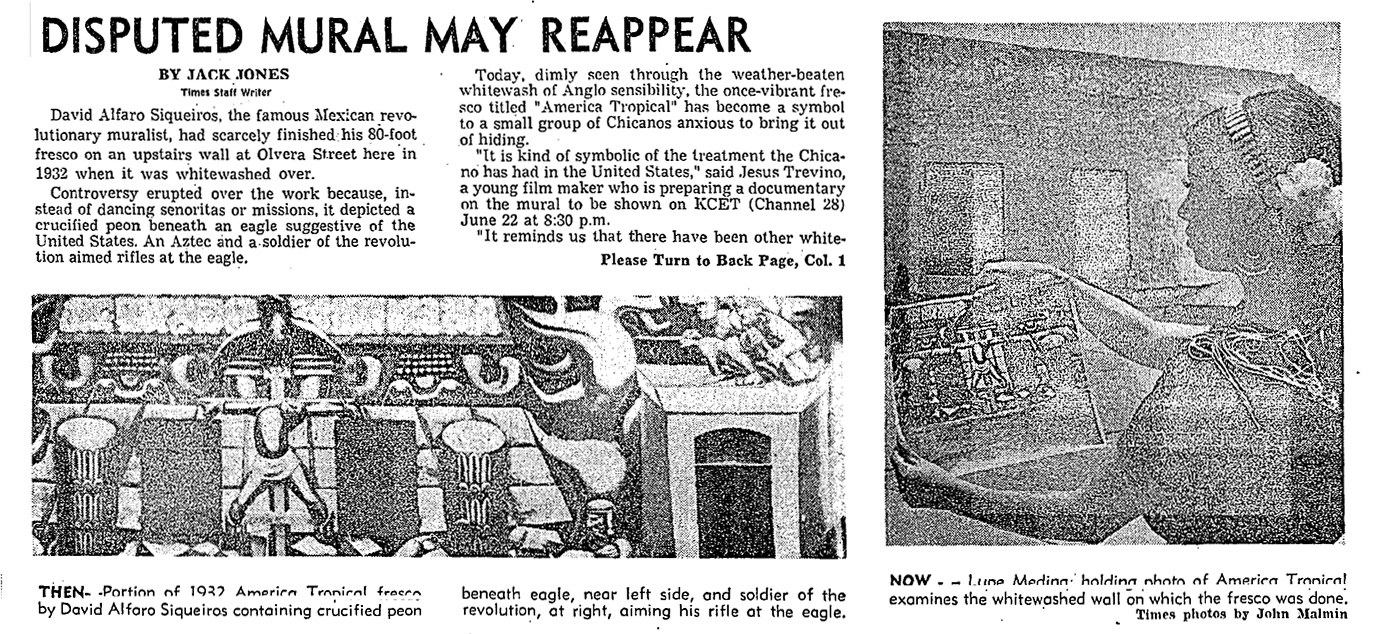

Shortly after completing América Tropical, Siqueiros' six-month visa expired, and he was denied renewal. He and his family were forced to leave Los Angeles quickly in November of 1932 for Buenos Aires, Argentina. In less than two years, the portion of América Tropical seen from the street was whitewashed. Several years after that, the entire mural was painted over.

Restoration Efforts

Although largely ignored by most of Los Angeles for the next 30 years, in the 1960s, artists and art historians, especially those involved in the Chicano Movement (El Movimiento), began reminding the City about the history of América Tropical and also started efforts to preserve it. By this point, the whitewash had peeled and faded, and it was possible to see parts of the mural underneath. Connections were also made with Siqueiros himself to get his input on the restoration. If it could not be restored to repaint, at least the central figure (unfortunately, the possibility of repainting it ended with Siqueiros' death in 1974). Documentarian Jesus Treviño created a short film about the mural and the preservation efforts, shown on KCET in 1971 (and sometimes rerun on that channel in the 70s and 80s). Promoting his film in 1971, Treviño told the Los Angeles Times that América Tropical is "symbolic of the treatment the Chicano has had in the United States. It reminds us that there have been other whitewashings and that we are faced with some of the same feelings in the early 1930s, a time of the deportations of Mexicans, the beginnings of the farm labor movement, and strikes."

Despite the dedication of art historians and artists such as Treviño, Shifra Goldman, Luis Garza, Josefina Quezada, Isabel Castro, and Jean Bruce Poole, efforts to preserve the mural were unsuccessful for many years due to a lack of financial and political support. However, reviving América Tropical's cultural importance in the 60s and 70 reminded the City of an important chapter in its history. The connections the Chicano Movement forged with Siqueiros' inspired him to create a commemorative print honoring slain journalist Rubén Salazar. The sales benefited the Plaza de la Raza Cultural Center. And artists in the Chicano Art Movement were inspired by Siqueiros and the Mexican mural movement, and they created their large-scale public murals with social, political, and personal themes throughout Los Angeles and Southern California.

In the 2000s, efforts to preserve the mural were finally realized. The Getty Conservation Institute stabilized the mural in 2002. In a public-private partnership with the City of Los Angeles began a project to create a protective shelter and viewing deck, and an interpretive center in the Italian Hall below. Unfortunately, the mural could not be restored to its original appearance. Siqueiros had used innovative methods to create the mural, including choosing cement instead of traditional fresco plaster. It was impossible to restore its original colors after the whitewash and exposure to the elements altered it. Additionally, no color photos exist of the mural, and art restorers would have been unable to accurately recreate the mural's colors. Although it would have been wonderful if the mural could have been completely restored, it is also fitting to show the effects of the whitewash on the mural, letting viewers see both the artwork and its history at the same time.

Before Siqueiros arrived in Los Angeles, most large-scale artworks complemented their sites using decorative or historical themes. His was perhaps the first artwork in the area to deliberately create antagonism with its site. The three murals he created in Los Angeles and the Chouinard class he taught, and the lectures he gave influenced many California artists from the 1930s on. His impact, along with other Mexican artists', can be seen in movements such as the WPA murals and the Chicano Art Movement. Now, as we approach the 90th anniversary of América Tropical's completion, street art that depicts social, political, and personal themes is part of the visual fabric of Los Angeles. Although as art curator and preservationist Isabel Rojas-Williams noted, the work of preserving murals, protecting artist rights, and enabling the creation of new street art is an ongoing challenge.

Murals and street art often confront people outside of galleries and museums, reaching wide viewership but always at risk from the elements, censorship, and destruction from anyone who might want to alter them. When Siqueiros created América Tropical in 1932, there was nothing like it in Los Angeles. It was one of the largest public murals then painted in the United States, it was outdoors, and it was uncompromising in its message. Although it was whitewashed to erase it from public consciousness, it was so important to the history of Los Angeles that through the efforts of activists, artists, and cultural historians, the artwork and its history remained. And now, when visitors travel to Olvera Street, the street also contains the América Tropical Interpretive Center. The whitewashing damaged the mural, but artists, historians, and activists ensured it was not erased.

American Rescue Plan: Humanities Grants for Libraries is an initiative of the American Library Association made possible with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities through the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.