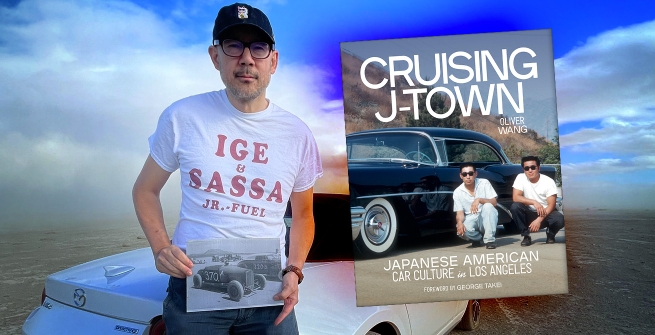

Oliver Wang is a professor of sociology at CSU-Long Beach and the author of Legions of Boom: Filipino American Mobile DJ Crews of the San Francisco Bay Area (Duke Univ. Press, 2015). Oliver is a regular writer on music, arts and culture for outlets including NPR's All Things Considered, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Los Angeles Times, and KCET's Artbound. He has co-hosted the podcasts Pop Rocket and Heat Rocks and is currently developing a new podcast on the songs of Asian America. He currently lives in the San Gabriel Valley. He is the curator for the Japanese American National Museum exhibition, Cruising J-Town: Behind the Wheel of the Nikkei Community, a summer/fall 2025 exhibition about Japanese American car culture in Los Angeles. He is author and editor of the exhibition's companion book of the same name and he recently talked about it with Daryl Maxwell for the LAPL Blog.

What was your inspiration for Cruising J-Town?

I was bewildered that no one had ever published a book about Asian Americans and cars. To me, it was such an obvious topic to focus on, least of all because the import car scene, which goes back to the 1970s, has been led by young Asian Americans. Yet their contributions to that and many other car scenes have received little attention in either the popular press or academic circles, despite being one of the most visible examples of Asian American popular culture for more than 100 years. Starting in 2016, a good friend (Hua Hsu) suggested that rather than spend more years complaining about the absence of such a book, I could do something about it. That's where I began, and while I still think it's absurd that it took until 2025 for a book on Asian American car culture to exist, at least one does exist now (thanks to Angel City Press!).

The exhibition Cruising J-Town opened just prior to the release of your book by the same name. How did you first envision Cruising J-Town? As a book or an exhibition? Did you always hope there would be both?

I started my oral history interviews in the summer of 2016, before there was an exhibition planned. To be candid, after spending a year or so doing interviews, I wasn't sure if I'd have the time and energy to put into writing a proper book. However, when the Japanese American National Museum came calling in 2018, inviting me to curate an exhibition that eventually became Cruising J-Town, it was a fortuitous best-of-all-worlds situation, providing me with a direction to take my work through two public-facing outlets: the exhibition and the book. We lost several years because of the COVID pandemic, but along with JANM staff, I resumed oral history interviews in 2022, eventually completing over 90 of them, and that became the basis for the stories shared in both the book and exhibition.

I'm guessing you had to work on both the exhibition and the book simultaneously. What was that like?

Challenging. The older I get—I just turned 53—the more I have to accept that whatever multitasking skills I thought I once had… those are gone now. I have to work in more of a linear order now, one project at a time. In 2024, that meant first finishing the exhibition script—an annotated list of every object to be included in the exhibition—by the end of May. Practically the next day, I had to start work on writing the manuscript, due five and a half months later. I made that deadline, but I don't recommend trying to knock out a book in less than six months! Looking back, it's a minor miracle I got everything done in time, but by doing so, it gave my editor, Terri Accomazzo, and book designer, Becca Lofchie, enough time for them to help get the book into its final, beautiful state.

In your introduction, you state that, while growing up in the San Gabriel Valley, you weren't much of a "car guy." When/how did that change? What drew you into the car culture of Southern California's Japanese American community?

As my wife has joked, I'm not a "car person" but I am a "car person-person." In other words, I'm interested in what others are interested in, especially when it comes to forms of Asian American popular culture. In the past, that's included writing about music and food, and for this project, it's all about car culture. However, despite working on this for so many years, I still don't think of myself as a car person—it's unlikely that you'll ever find me tinkering with a vintage Datsun 510—but I certainly have a much deeper appreciation for cars and the culture around them.

How long did it take you to do the research and then bring Cruising J-Town, both the exhibition and the book, to fruition?

Pre-exhibition, I was doing oral history interviews on my own from 2016 to 2018. When JANM approached me in 2018 to curate the exhibition, things slowed down for a bit as we began to discuss the scope of the project, and then, of course, the pandemic completely halted things in 2020 and 2021. However, by the beginning of 2022, we started back up in earnest. Since then, I've worked on some aspect of this project more days than not. It is, by far, the most ambitious project I've ever taken on, both in terms of time and collaborators. It's a capstone of my professional career, embodying my values and priorities as both writer and scholar in ways that far exceeded my original imagination.

What were some of the more interesting or unexpected things that you learned during your research?

On a very simple level, everything I learned was interesting and unexpected because I went into this project knowing next to nothing about these histories. However, through both our oral history interviews and archival research, I learned an incredible amount about—again—everything! To highlight a few outstanding examples: The Fish Trucks. From the late 1940s through early 1990s, dozens of drivers would deliver fresh seafood and other Japanese food goods to Nikkei households around the greater L.A. area, six days a week, working brutally long hours, driving hundreds of miles every week (if not day). And while this was a form of work for these drivers, they were also performing a great community service, helping those who would have found it difficult to make the drive from where they lived back to Little Tokyo to shop in Japanese specialty markets. For many Angelinos above a certain age, they remember the Helms Bakery truck or a local milkman, and for Japanese Americans down here, their local fishman would have been an equally fond memory.

The role of cars/trucks during the World War II incarceration experience. The wartime incarceration of 120,000+ Japanese Americans is one of the most documented moments of American history. In digging into that history, especially through the archives, I was able to find all kinds of stories and policies that put a spotlight on the unexpected role that cars and trucks played within it. It was fascinating to learn about all the ways that, even behind barbed wire, the automobile was part of this dark history as well: families driving themselves to be incarcerated (or to flee it), the important role of motor pools inside concentration camps, examples of vehicular recreation (read: joyriding) enjoyed by young people in camp, and so forth.

Postwar drag racing. I knew almost nothing about drag racing besides "cars go fast on track," but I now have a much better understanding of how it fits into a larger history that included both pre-WWII dry lake racing in the Mojave as well as the long tradition of street racing. In all these spheres, Nikkei drivers were heavily involved on both the amateur and professional levels. I'm especially enamored with the story of the Go-Hon's, a hot rod club out of Pacoima made up of mostly gardeners and gas station operators who built their own roadsters and dominated the San Fernando Drags in the late 1950s. We have extraordinary color slide images of the Go-Hon's in the book.

How was George Takei selected to provide the introduction for Cruising J-Town? Had you worked with him before, or was there some other factor?

When my associate curator, Chelsea Liu, was going through the JANM archives, she came across a 1965 photo of George Takei standing next to Takeo "Chickie" Hirashima, one of the great Indy car mechanics and engine-builders of the 20th century. We were instantly intrigued by the story behind the photo. By inviting George to write the foreword, I learned that the photo was from a production shoot for the stock car drama, Red Line 7000 (1965) in which George was cast as Kato, a racing mechanic. This was before he was cast in Star Trek and Red Line 7000 was one of his first credited movie roles. As it turned out, while I thought Kato was based on Chickie, George told me that filmmaker Howard Hawks wanted the character to be Japanese American because, in real life, Hawks's personal mechanic was JA. At the time, George didn't remember the name of the mechanic, but luckily, thanks to our oral history interviews, I figured out that Kato had been inspired by Little Tokyo mechanic Jack Kuramoto of Jack's Auto Service on 2nd and San Pedro. When I shared all this with George, he recalled that his mother's cousin worked at Jack's Auto Service! He turned out to be a perfect foreword author because even though he's not a "car person" either, there were all these connections between his and his family's lives that tied into many of the community stories our project sought to share.

What was your first car? When/how did you get it?

My first car was a hand-me-down from my parents: a 1980 Chevy Citation, widely considered one of the worst models Chevy ever produced. It was a woefully underpowered 4-speed with only a radio and single speaker... which I blew out; I had to bring a small boombox into the car if I wanted to listen to any music. Still, it was my car and that's what mattered.

What do you currently drive?

A 2020 Tesla Model 3. Especially in light of Elon Musk's descent into fascism, I'm less excited to own it now vs. when we first bought it, but I have to say, it's also the most enjoyable car I've ever owned when it comes to driving. I've driven EVs since 2017, and I'm so accustomed to the nimble, linear acceleration of their engines that driving a car with a conventional internal combustion engine feels "off" now.

Do you have a dream car (one that you don't currently own, but hope to one day)? A car out of all of the cars you've seen during your research, you wish you could own?

I've always loved the idea of owning a convertible, dating back to when a high school SAT tutor gave a bunch of us students rides home in his droptop Mustang. Now, having interviewed Tom Matano, who was in charge of the Miata roadster project for Mazda in the mid/late 1980s, and having driven three different Miatas over the course of the past year or so, I would seriously consider getting one once I retire. It's not a practical commuting car, but if I didn't have to commute, why not?!

If you could ask Fred Jiro Fujioka, the head of the American-Japanese Automobile Association, who organized the "World's First Japanese [Auto] Race." In Los Angeles on August 8, 1915, what would it be?

I'd want to know what was it about the automobile that fascinated and motivated him. I assume he saw something transformative in the age of the automobile that inspired his ambitions to be an industrialist and enthusiast.

If you could tell him something about the relationship between Japanese-Americans and their vehicles that has developed over the intervening years, what would it be?

I would want him to know there would be generations of Nikkei who would shape the transpacific development of car culture in both the U.S. and Japan. While Cruising J-Town is dedicated to the entire Japanese American community, I would have wanted him to see his own visions and life's passions reflected in the book's pages.

What's currently on your nightstand?

I have a literal stack of books I've bought over the past year, but I've been so busy with everything around the exhibition and book launch that I haven't had a chance to even take some of them out of the shrinkwrap yet.

I'm definitely looking forward to reading Jeff Chang's new Water Mirror Echo: Bruce Lee and the Making of Asian America, which comes out Sep. 23 (see my answer to the next question for more context). As someone who is hoping to teach a few courses in Tokyo next year, I want to finally crack into W. David Marx and Roni Xu's recent Shōwa Guide Tokyo, their exhaustive guide to all the surviving 20th-century kissaten-style bars and cafes that are steadily disappearing in the city.

And on a professional level, I need to start reading Kelly Chong's Love across Borders: Asian Americans, Race, and the Politics of Intermarriage and Family-Making. It's from 2011, but it's one of the few studies to ever discuss interethnic Asian American families (i.e., families in which both parents are Asian American but not from the same ethnic groups: Chinese/Japanese, Filipino/Thai, Vietnamese/Korean, etc.). This is connected to one of my next projects (discussed below).

Can you name your top five favorite or most influential authors?

- James Baldwin. Like many who grew up being assigned The Fire Next Time, I marveled at the ways in which Baldwin spoke truth to power through his extraordinary prose. His essays inspired my aspirations to be a writer. For years, the background image on my laptop has been a Sedat Pakay photo from 1966, where Baldwin sits in front of his Olympia SM-7 typewriter. My students, every semester, see this image countless times as I'm setting up for my lectures, but only a tiny handful ever know who it is.

- Jeff Chang. I met Jeff when I was an undergraduate at UC Berkeley, writing a class paper on Asian Americans and hip-hop, and needing folks to interview. Jeff and I became good friends, and not only was he the first Asian American cultural critic whose work I ever came across, but Jeff also helped me get my first gig, writing music reviews for URB Magazine circa 1995. In a very basic way, realizing that another Chinese American was writing about music and culture helped me realize, "This is possible for me, too."

- Greg Tate. I discovered Greg through his 1992 anthology, Flyboy In the Buttermilk. At the time, I was looking for examples of hip-hop criticism since that was what I was aspiring to write myself. As I learned about Greg, through the years of reading his work, was the expansiveness of his arts and culture knowledge: his ability to link different artists and movements across time and genre was remarkable. Also, his writing was so inventive and playful; he constantly created new terms in a way that felt completely organic to how he wants to communicate ideas that weren't being served by our existing vocabulary. Greg's passing in 2021, at only 64, still shocks me to think about, but I'd like to think his presence is still felt in all the generations of culture writers and critics he helped influence.

- bell hooks. As both a writer and scholar, I'm constantly dismayed at how inaccessibly (and unnecessarily) obtuse academic writing can be, so it's always been refreshing to find scholars who write with clarity and coherence. bell hooks was already a prolific essayist by the time I started reading her books, and because she also took pop culture seriously, I found all kinds of inspiration from her work. That she and Greg Tate passed away just weeks apart, before either turned 70, was such a blow to the many communities of writers, artists, activists, organizers, and scholars who grew up at their proverbial feet.

- Hua Hsu. I first met Hua in the mid-1990s when he was an undergrad at Cal and I was in grad school there. By the early 2000s, thanks to instant messenger technology, we started to "talk" on practically a daily basis. As I mentioned earlier, Hua was the friend who suggested that if I felt so strongly that there needed to be a book about Asian Americans and cars, I should go out and write one. Beyond that, though, Hua's such a gifted writer and I frequently turn to his work—or that of his former Bard colleague, Lucy Sante—whenever I need some good writing to jostle me out of my writer's block.

What was your favorite book when you were a child?

It's hard to pick one! Most of the books that come immediately to mind all have one thing in common: they're all escapist adventures in which people, kids or otherwise, had the autonomy to explore the world on their own terms. That includes everything from E.B. White’s The Trumpet of the Swan to Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach or The Fantastic Mr. Fox to Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth to C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe. I mean, who amongst us didn't read the latter and immediately check our bedroom closets for a secret portal to a different world?!

Was there a book you felt you needed to hide from your parents?

No. There were books they hid from me, but that's for another time ;)

Is there a book you've faked reading?

Only the ones written by my friends. I'm joking. Mostly.

Is there a book that changed your life?

Not really. I hadn't thought about this until now, but while reading and especially writing have been transformative in my life, the truly transformative force in my life has been music. I have a hard time thinking of a book that changed my life, but I can instantly tell you the album that did: De La Soul's 3 Feet High and Rising (1989). It's also not unusual for me to buy an album just for the cover art. These are underbaked self-reflections at the moment, but it's dawning on me that I buy books because I appreciate the ideas, stories, and writing contained within them, whereas I collect records because, as objects, they also hold meaning for me beyond just the music they contain.

Can you name a book for which you are an evangelist (and you think everyone should read)?

Two come to mind, both from James Baldwin. The first would be his novel, Another Country (1962), which I first read in 1997 (shout out to Josh Kun, who assigned it in a class of his I was auditing while in grad school). At that point, I had only ever read Baldwin's non-fiction, and I was utterly blown away by the storytelling and prose in Another Country and Baldwin's ability to capture sentiments about passion, anger, empathy, and forgiveness. I think, all too often, about this line in the book, between Ida and Cass: "Some days, honey, I wish I could turn myself into one big fist and grind this miserable country to powder." Baldwin's gift for writing about both unrelenting rage and limitless love—often times in the orbit of the other—was astounding.

Meanwhile, I'd also recommend Baldwin's essay collection, The Price of the Ticket (1985). It's an incredible compendium of cultural criticism, especially for reprinting "The Devil Finds Work" (originally published in 1976), in which he ends with a scathing discussion of The Exorcist except that he's not only talking about the film, he's also talking—as he often did—about America. His closing paragraph is one of the devastating things I've ever read. I just re-read it right now, and it still gives me chills.

Is there a book you would most want to read again for the first time?

I'd probably have to go back to one of those books from my childhood that so engaged and ignited my imagination. It's hard to choose just one off that list, but James and the Giant Peach comes to mind because it's so surreal and fantastical: a boy sails the ocean in an enormous peach, accompanied by equally oversized, intelligent worms and insects. Who comes up with that?!

What is the last piece of art (music, movies, TV, more traditional art forms) that you've experienced or that has impacted you?

I’m biased but I loved Hua’s memoir, Stay True. It was beautifully written and incredibly thought-provoking, especially his passages about the nature of friendship. His descriptions of coming of age in Berkeley in the 1990s spoke to many of my own experiences as well. Even more than that, my 20-year-old daughter finally read it, earlier this summer, and she was telling me how she identified with some of Hua's experiences and sensibilities in the book. To me, that meant she was also, indirectly, identifying with my experiences too. As a parent, I want to make sure I see her for who she is (and not just who I want her to be), but by the same token, I want her to understand something about me as well. If Stay True is a proxy for that, I treasure it even more.

My wife and I watch a decent amount of television, and we both loved season two of Andor. I thought it was brilliantly written, paced, and acted. That it's also an unflinching story about what it takes to fight fascism is obviously timely and important. The last song to hit me in the feels is one that I just learned about in June: a cover of Mike Williams's Vietnam War-era single, "Lonely Soldier," recorded in Panama by Los Authenticos Mozambiques. It has this rawness to it that's not on the original, partly thanks to the group's booming brass section as well as singer Jaime Murrell's impassioned performance.

What is your idea of THE perfect day (where you could go anywhere/meet with anyone)?

Waking up after a good night of sleep, a lazy morning with no work to do, and at some point, a good meal with good friends, old or new. That feels like a luxury (especially the "no work" element).

What is the question that you're always hoping you'll be asked, but never have been?

"Where can Cruising J-Town go next?" comes to mind. People have asked me what I plan on working on next—it's literally the next question in this questionnaire!—but I'd hope there are people who read the book or see the show and think, "could I do something like this with __________?" That could mean people in other cities looking into other regional examples of car culture in their communities. It could mean doing deeper dives into any of the areas our project was only able to scrape the surface with. Or it could mean someone coming to the same realization I did: if you start by collecting stories from your elders and community members, you have no idea where it leads, and at the very least, you're collecting those stories while they're still here to be shared.

What is your answer?

As proud as I am about what me and everyone else who worked on this project were able to accomplish, I don't want to this to mark an end. I'd hope it might motivate others to pursue similar projects, wherever and however. There are so many community stories waiting to be shared and told.

What are you working on now?

I'm still in the middle of exhibition-related programming, but I'm beginning work on a new research project about interethnic Asian American families. This is with Dr. erin Kieu Ninh at UC Santa Barbara, and it started with us joking about how both of us are married to Yonsei (fourth-generation Japanese Americans) but neither of us are JA ourselves (I'm Chinese American, erin is Vietnamese American). However, we quickly realized that while there have been years of research on interracial Asian American families, there has been surprisingly little research done on interethnic Asian American families, even though, at least in our respective friend groups, most of the Asian American families we know are interethnic. Similar to how I was drawn to the project that became Cruising J-Town because I felt like there was a conspicuous void in existing research, it's also the case here that I feel like erin and I might be in a position to contribute to a topic that, thus far, has seemed under-studied.

I also have a few articles/essays I need to complete, including one about "sample snitching," another one about how "Bizarre Love Triangle" became the unofficial anthem for Asian American Gen-Xers. I also want to get back to podcasting; my last show, Heat Rocks, went on hiatus in 2021, but me and my recording partner, Morgan Rhodes have been talking about trying to revive it. As I shared earlier, though, I have to work more linearly now, so it's hard to juggle all my ambitions simultaneously; I have to learn to check one item off at a time, and right now, I haven't adequately organized things yet. Bird by bird, as the saying goes.