As a born-and-raised Angelino, there are places in this fair city of ours that always evoke strong feelings and memories. For me, one of those places is the Los Angeles International Airport, also known as LAX. The last thing you see before exiting to baggage claim and the promise of traffic and exhaust fumes is a beautiful, wondrous mural. Made with hundreds or thousands of little glass tiles, the art piece spans the length of the hallway, changing colors slowly from one end to the other. Some think of the changing seasons or maybe the changing landscapes which you've just flown over, or even a feeling of serenity and well-being before returning to regular life.

I've always wondered who created this masterpiece. For the longest time, I thought it was Charles D. Kratka, Head of Interiors at the design firm Pereira & Luckman—that's what a quick Google search will tell you. But a deeper dive turned up oral history told by Janet Bennet to LAist and the Los Angeles Times, saying Kratka used her design. My librarian-research senses went off immediately, so I started digging—both to get to the truth and because I'd long heard a different story about the mural's origin, and who really created this epic wall of art. Honestly, I found it hard to believe that something of that scale and scope could be the work of just one person armed with a giant bucket of tiles.

After some initial research, I saw that the story was much more interesting and complicated than I had imagined. What I uncovered was that the company Byzantine Mosaics, the firm of Alfonso Pardiñas, executed the mural (the design has been credited to Janet Bennet) and likely helped shape both the vision and color choices. I talked with Alfonso's daughter, Ilka Erren Pardiñas, to get to the bottom of who created this iconic mural.

Hi Ilka, thanks for talking to me about this! I'm so excited to get to the bottom of this mystery. First, can you tell us about your dad?

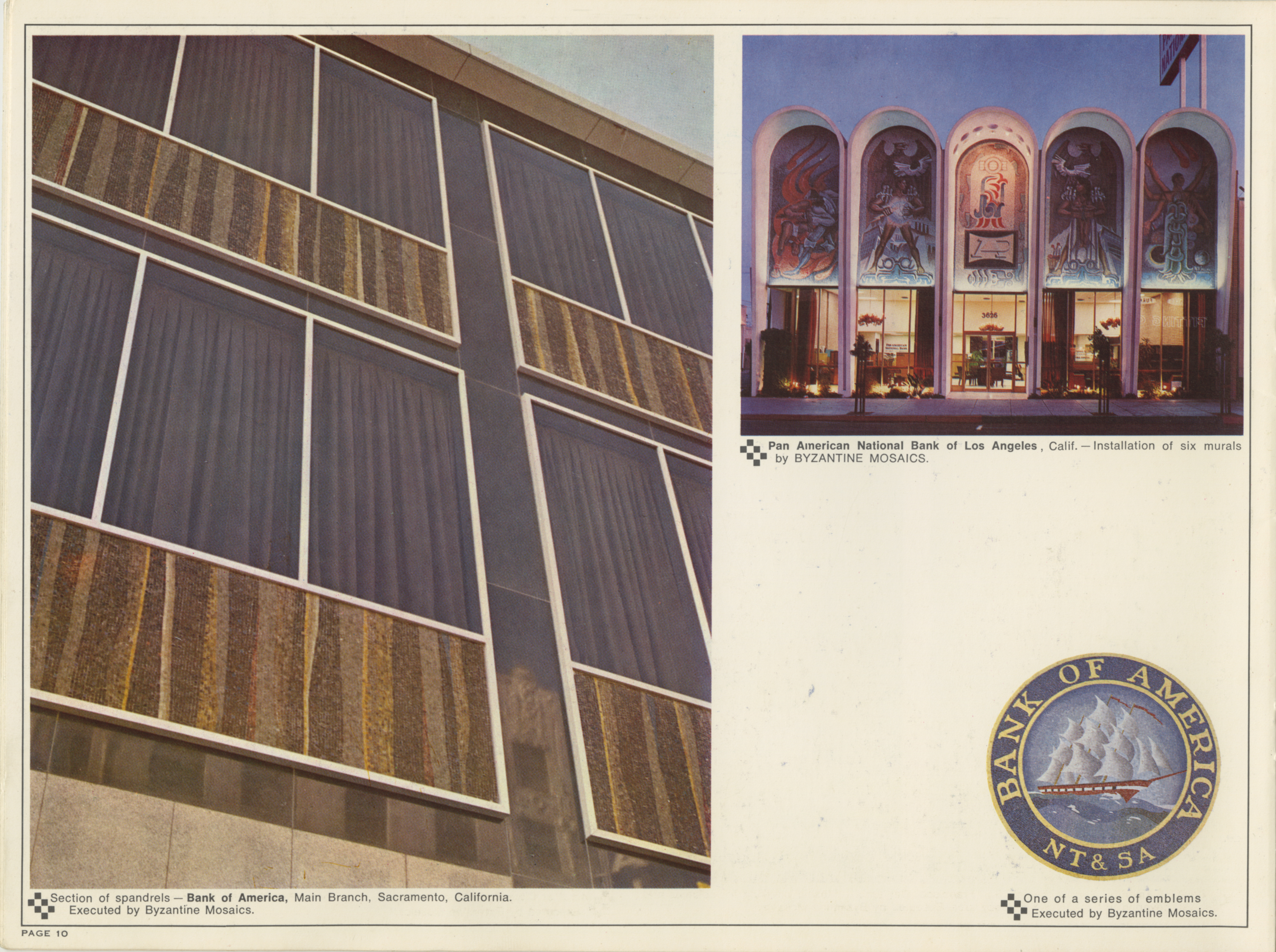

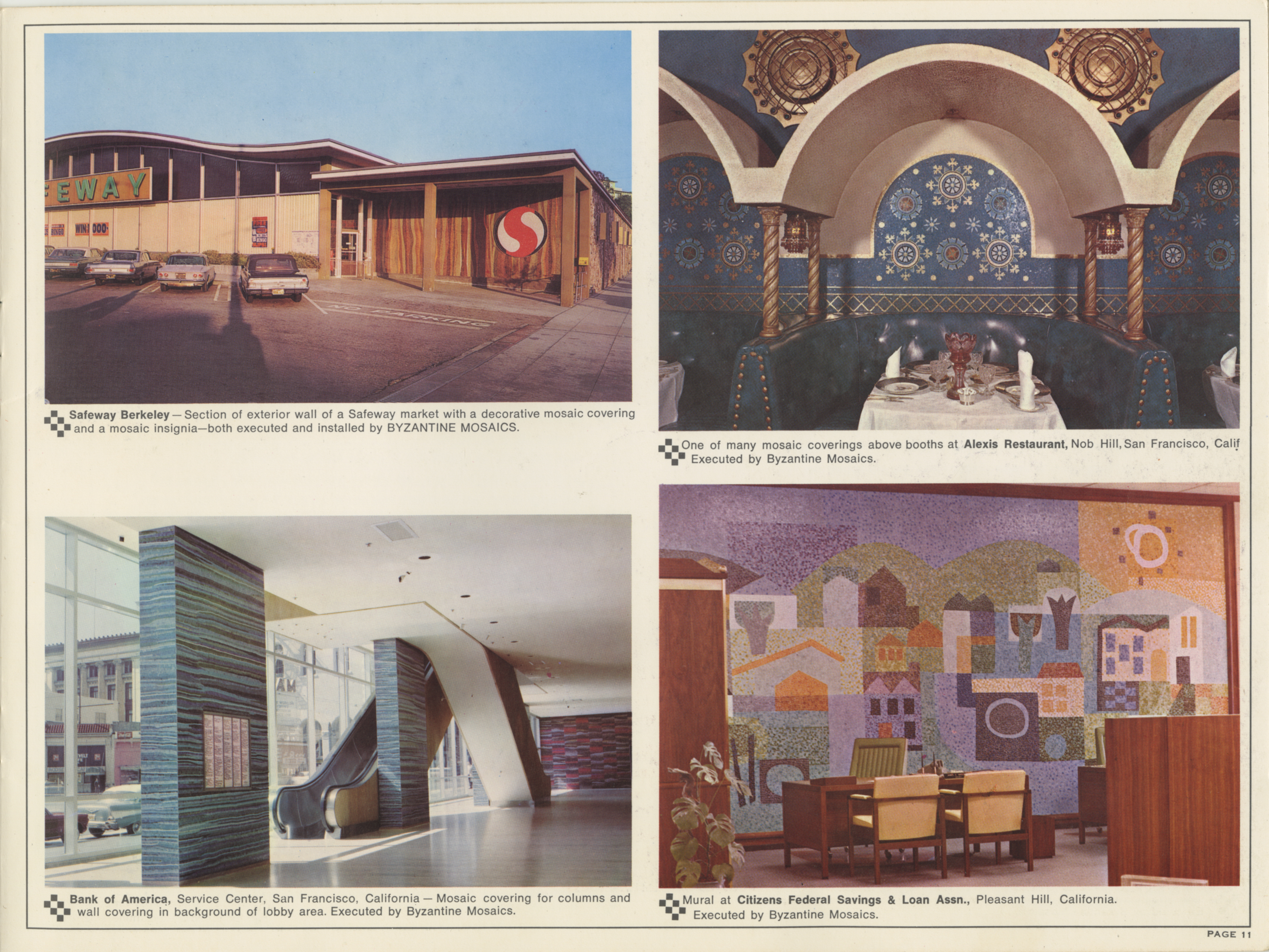

My dad, Alfonso Pardiñas, was born in Coyoacán, Mexico, on August 24, 1924. He moved to California around 1941. He became a U.S. citizen as a young man and served in the U.S. military. In 1948, he studied with the renowned German mosaicist, Theodore Hanisch. Early in his career, he worked in Mexico (mainly in the capital) on pieces by artists like José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Rufino Tamayo, José Chávez Morado, and Juan O'Gorman. He was a prominent fixture of the San Francisco bohemian art scene in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. He collaborated with Bay Area-based artists like Beniamino 'Benny' Bufano, Jean Yanko Varda, Ruth Asawa, architect Leonard Cahn, and painter Alex Anderson. He founded the San Francisco-based company, Byzantine Mosaics. His associates included Mexican muralist and fresco painter Jorge Rodriguez, who graduated from the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City, and Manuel Perdomo, whose father financed and co-founded (together with Alfonso) the first mosaic factory on the American continent. The company received frequent and sizable public and private contracts executed all over the U.S. However, the majority can be found in and around California (U.S. Post Office, Bank of America, BART). Alfonso Pardiñas and Byzantine Mosaics were often contracted to execute monumental works for churches of varying denominations. One of the best known and most visible is the Holy Virgin Cathedral (the Russian Orthodox church with prominent gold onion domes) in San Francisco's Richmond District.

Much of his work has been destroyed over the years, often unwittingly. Only a few pieces are publicly credited to him or to Byzantine Mosaics. Research remains to be done to unearth copies of the work contracts proving he executed extremely well-known pieces, such as the famous mosaic hallway at the Los Angeles International Airport. The Byzantine Mosaics files with the original commissions were lost or destroyed in the years since his death. Alfonso Pardiñas died in San Rafael, California, on September 22, 1975. He is survived by three daughters, all born in California between 1956 and 1964 (Francesca, Iza, Ilka), and his nephew, Memo Morantes.

Alfonso cut a fine figure at meetings and in person. He dressed impeccably and quite artfully within the parameters of what would still be considered gentlemanly. He was handsome and charming. Extremely charismatic. People in all stations of life (young/old; rich/poor) were drawn to him. He was a bon vivant. He was a man with style and flair. He was a very sharp dresser. He was a very dapper dude.

Wherever we'd go with him, all around San Francisco, people would know or want to know him. The red carpet was always rolled out for him. We were invited everywhere: operas, the symphony, ballets, and performances. He moved in high society circles with ease and grace. But was most frequently in the company of other artists, poets, dancers, and musicians—everyone just getting wild. It was still "Summer of Love" vibes in San Francisco, and everything was free and flowing.

He had a deeply spiritual side. He was self-educated and was an avid reader. He studied philosophy and meditation. He practiced yoga daily. He was a very advanced Yogi, executing extremely difficult positions and holding them for hours.

Can you discuss why your dad hasn't been officially named?

Regarding the LAX hallway, I am not sure who has ever been officially credited by Los Angeles World Airports (LAWA). It might be that no one connected to the work has been formally credited. I have not looked into it extensively, but it might be that Charles D. Kratka's estate simply credited him in the obituary. And then, eventually, Janet Bennet started telling her story. Interestingly, Bennet began telling her story around the same time I started to work on my dad's story more publicly. I began my work in 2006. I never thought I would personally have to "uncover the truth" and get him credit. I thought I would just be the catalyst, raising interest, and that a historical preservation society (particularly in San Francisco) would take over the work. So far, that has not happened.

Alison Martino at the Vintage Los Angeles blog seems to be the first (to the best of my searches) to reference Janet Bennet and take her at her word. That article was first published in 2014. Both Alison Martino and Louise Sandhaus at Design Observer (she published her piece in 2017) were kind enough to reply to me in emails and then to update their articles to include a credit for Alfonso Pardiñas and Byzantine Mosaics. Jen Carlson at LAist credits Bennet in an article posted in July 2016 (I did not reach out to her).

Since then, a few Wikipedia articles have also credited my father, and a LocalWiki page has been created for him. A big feature story published by Dave Weinstein at the Eichler Network has done a lot to tell my father's story.

Can you give us a little context about Alfonso's firm, Byzantine Mosaics?

My dad founded Byzantine Mosaics and was the visionary behind the operation. He was the face of the company and the main person who made all the deals and landed all the clients. By all accounts, He was an amazing salesman and deal closer.

Besides having an artist's gift for colors and their application, he had the gift of winning people's confidence for the beauty he could create. The clients could follow his descriptions and fully visualize what he would deliver. He could show them his work and offer to create samples for them (some of which my family still has—panels created for church projects, a BART station, color palettes). This was very persuasive, and he was able to land big contracts and commissions.

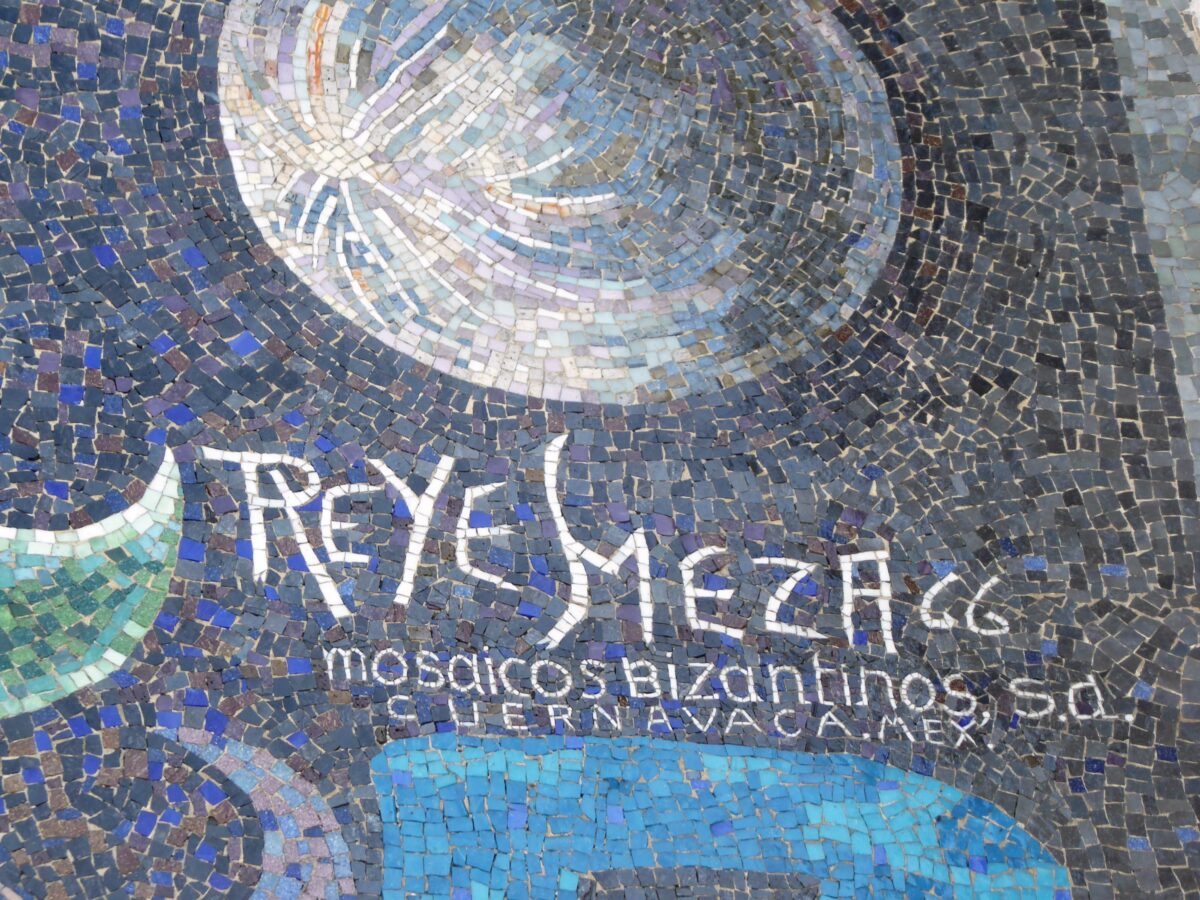

Even though he had almost no contact with his family in Mexico, he traveled to Mexico regularly for business. He also executed large works there, and all the mosaics for his work came from the factory in Cuernavaca that he co-founded.

Are Byzantine Mosaics still around?

Somewhere along the line, the Perdomo Family fully took over the mosaic factory, and the family still runs it to this day. They have switched the name from "Byzantine Mosaics" to "Mosaicos Byzantinos." They maintain a website and have published a book: Mosaics in Mexico, The Perdomo Family's Workshop by Miguel Angel Fernandez.

Can you explain a bit how murals of this size and scope are created?

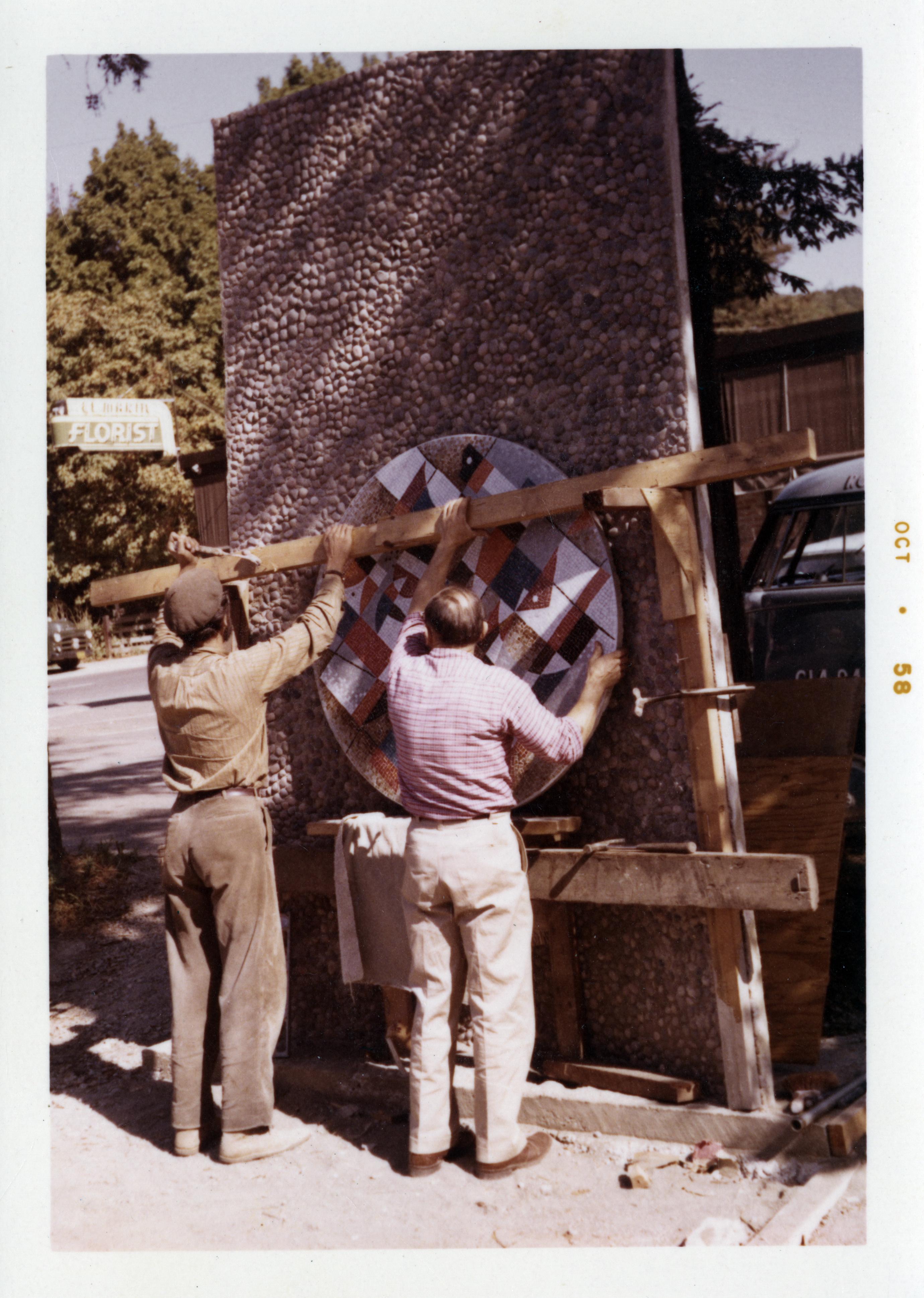

I am not a mosaic expert, but I did basically grow up in a mosaic workshop. At least the years my dad was still alive. Because he often lived in his workshops. So when we'd live with him (my parents divorced when I was about two years old, and my dad died when I was 11 years old) on weekends or when my mother, Cristina, was on her long travels, we'd be in the thick of it in the workshops. They were big warehouse spaces because the pieces were mostly enormous. The whole side of a building, for instance. Or the massive interiors of churches. The shop was filled with rows of mosaics. Towering aisles of boxes of mosaics in every color imaginable. Bags of cement. Tools, wood, metal—everything needed to make the mosaics.

The artist would render the original artwork, and then a draftsman would draft it to scale. These huge murals would then be divided into panels. The "reverse" of each panel would have not only the outline of the artwork but also notations describing the colors and styles of mosaics to be used. These would then be applied by hand.

Once that was complete, the reverse side was pressed into cement (usually there was a wood backing with a frame, sometimes brass or other metal around it, or a wood frame). That's what the mosaic is pressed onto.

When those panels are set (when the concrete has dried), they can be transported and then mounted at the construction site.

In addition to the LAX mural, are there others still standing we can visit?

Although a huge number of pieces have been lost or destroyed, especially pieces considered "commercial art" (Bank of America, Wells Fargo, US Post Office, and Safeway signs), many are still intact and still in public places. The PEACE statue by Beni Bufano (Alfonso did the mosaic work) that used to greet people at SFO is now on Brotherhood Way in San Francisco. The aforementioned onion domes and six saints of the Russian Orthodox Church in the San Francisco Richmond District. The Virgen de Guadalupe in the Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Assumption in San Francisco. Most banks and churches have maintained the artwork. Several BART stations maintain the work my father executed. The famous Jean Varda mural that was commissioned for the Ramada Inn (originally adjacent to Fisherman's Wharf) was moved to Sausalito (when the building was demolished), where it is still on display. The Ruth Asawa piece titled "Growth" can still be seen at the Bethany Center. Many other pieces in and around San Francisco, and beyond, can be viewed and enjoyed by folks who seek them out or develop an eye for recognizing the Byzantine Mosaic trademark style.

Are there ones in Los Angeles I can direct our readers to?

The Pan-American Bank in East L.A. is located on the corner of 1st Street and Townsend Ave. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2017. From the L.A. Conservancy website: "As one of the oldest continuously operating Latinx community banks in the country, the 1965 Pan American Bank building is significant for its association with the economic development of East Los Angeles after World War II. It provided critical bilingual financial services to Mexican and Mexican American residents and businesses, who often faced discriminatory policies at other financial institutions."

Where are you at in terms of getting official recognition for the LAX Hallway Mural?

My outreach to Los Angeles World Airports (LAWA) has been limited and met with silence so far. As a publicist by trade, I decided that my best option could be to simply "do publicity" for my father's body of work. Perhaps by drawing more attention to the question of who created the work and who executed it, a more qualified person or organization would step forward to solve the mystery. That has been my plan. But now I see I may need to rethink this.

I see that your dad worked with known artists and collaborated on various projects, such as Jean Varda and Ruth Asawa. Can you talk a bit about their relationships?

Alfonso was loved by all and loved everyone. It was always a highly reciprocal, mutual admiration society among the collaborators. Many of the artists were like family. Sisters and brothers to him. He loved them all dearly and loved to make sure everyone was elevated to the highest level of connection.

He loved to gather people together to philosophize, have deep political discussions, exchange ideas, and be creative. He loved to explore the work of forward thinkers and innovators. Many of the artists were immigrants or descendants of immigrants from Italy, Greece, Japan, and Mexico.

Why do you think it's so easy to dismiss the works of people of color?

In my father's case, I think the world at large—those who did not know him or work with him personally—sought to downplay his role as an artist and creator. Perhaps this served to keep from having to pay more. Instead of being viewed as a priceless piece of art, the work might just fall under artisan work or decorative arts, or just construction-related work, like tile laying.

And perhaps because of my father's business model, people did not feel Byzantine Mosaics should get name credit. His work had, after all, been commissioned and paid for.

Not giving full credit to the artists seems to have been pretty common. I can see that the families of others (Asawa, Varda, Bufano) have had to work hard to keep the legacy of these artists alive. The families have ensured their work is respected, admired, understood, and valued. So I guess I need to just keep working to do the same for my father. That is, in fact, why I had the idea for the" Preserve Alfonso Pardiñas Art" (PAPA) project. The primary objective is to connect the dots. Find all the pieces, and find the artists my father worked with. Create a thorough archive. Find a way to protect the pieces and also to credit pieces properly—like the LAX hallway.

I have to ask, did your dad work on any libraries?

Yes, Alfonso did work on at least one library that I know of. The cover of the Byzantine Mosaics brochure depicts one of the amazing collaborations he did with Jean Yanko Varda. It was executed for the Stockton Library in Stockton, California. It is possible that there was work on other libraries, but I unfortunately do not have proof or details to share.

[author's note: I discovered there are actually two murals by Varda at the library; the images are below]

Books and libraries were always my sanctuaries growing up, and still are today. I love books, and therefore libraries are holy places for me. I still recall getting my very first library card at the branch in North Beach in San Francisco. I spent many, many hours at libraries both in school and around town. Later, the main branch library in Civic Center in San Francisco became one of my favorite places to go. Living and studying in Germany, I spent lots of time at the university library, but the Deutsch-Amerika Haus library in Heidelberg, Germany, was my home away from home there. When I first moved to Los Angeles, I would spend time in the Hollywood Branch library, scoring the music trades for job listings. Later, the Los Feliz branch was my sanctuary (both the old and new locations). And now I visit the Cypress Park or Eagle Rock Branch. But also have a huge fondness for the Pasadena branch.

Papa always had several well-used and well-loved Yoga books with him. He read in both English and Spanish. He was a student of philosophy and yoga and was deeply interested in the arts. He ceaselessly pondered profound queries such as "What is art?" "Why does art matter?" "How does art evolve in the modern world?"

He loved the works of deep thinkers, including Pablo Neruda, Rumi, Omar Khayyam, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Nietzsche, Dostoevsky, Kafka, and Tolstoy.

Two books I know of that mention my father include the Beni Bufano coffee table book, and also the Jean Varda book by Betsy Stroman, The Art & Life of Jean Varda (2015).

Stroman spoke to me about her book. And it was actually partially what lit a fire in me to hurry up and try to document my father's story and work. Her questions helped me understand that there was not much documentation on Alfonso or Byzantine Mosaics. It became clear that history would erase my father's name if I did not create the source material that researchers and authors like her sought while writing their own books. I appreciated that she gave my father a sidebar in her book. I just wish it were more, considering that my dad was a huge part of Varda's life and work. Alfonso and Varda were extremely close friends and worked together extensively. But therein lies the issue—without an archive and accreditation, and with most of the adults who were eyewitnesses now dead or dying, the situation is becoming critical. I guess I always relied on those people who were my father's contemporaries to do this work. But one by one, they all died, and still no archive exists, only the small bit I have managed to build.

The Beni Bufano art book, Bufano: Sculpture, Mosaics, Drawings, features a photo of my father working on the mosaics with Bufano. And one of the workshops depicted was my father's shop. The book miscredits the group of images showing my father with a caption that instead says "School children at work on mosaics in the artist's studio. San Francisco."

Thank you so much for taking the time to talk to us at the Library. Is there anything else you'd like to add?

It is my dream to have a complete catalog or archive of all the pieces my father worked on and created. I'd like to be able to correctly credit all the collaborators and list the locations of each piece. Maybe even have a catalog of the pieces that have been destroyed. And it is essential to keep the existing pieces in good condition. Make repairs as needed. That is something I'd love to collaborate on with the Perdomo Family. Ultimately, it would be ideal to be able to safeguard all the mosaics.

Thanks so much for your interest and for helping me talk about my father's body of work. Means the world to me. Thank you.