On April 30, 1975, the United States Armed Forces Radio in Vietnam broadcast the following: "The temperature in Saigon is 105 degrees and rising," followed by the song "I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas." The American Embassy distributed the instructions surrounding this sequence to U.S. citizens and others expected to evacuate to signal the final evacuation of Saigon, thus marking the withdrawal of American troops and the end of United States involvement in the Vietnam War. Once the sequence was aired, American civilians and at-risk Vietnamese were expected to evacuate immediately to be airlifted out.

The end of the war is best known for this photo of an American helicopter evacuating Vietnamese officials and their families from the rooftop of an apartment building in Saigon, South Vietnam, on April 29, 1975. The stairwell is on permanent exhibit at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library & Museum.

Among Vietnamese, this war is only a small part of an over-a-century-long struggle in Southeast Asia for self-rule. This struggle is shared among communities throughout Southeast Asia, including Cambodia, Laos, the Hmong, and other indigenous groups of the region. During the French colonial period (1887–1954), these countries, along with their indigenous populations, which included the Hmong, were referred to as French Indochina. The armed struggle for self-rule that culminated this first struggle (1946–1954) is called the First Indochina War.

In July 1954, with the signing of the Geneva Accords in Switzerland, which marked the end of French colonial rule, French Indochina was divided: Vietnam was temporarily separated into two zones—a northern zone governed by the Viet Minh (later the communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam), and a southern zone governed by the democratic State of Vietnam; communist troops and guerrillas were to evacuate the Kingdom of Cambodia and the Kingdom of Laos. During this time period, in fear of religious and political persecution, there was a mass exodus by northern Vietnamese into South Vietnam.

The war fought from 1955 until the Fall of Saigon in 1975, which is also called the Second Indochina War, is taught in the United States as a part of an international conflict involving the Americans, the Soviets, the Chinese, and these three countries. This undertaking from the United States was a long and unsuccessful effort to prevent communism from spreading throughout Southeast Asia.

Among Americans, this war has been and continues to be a contentious chapter in United States history, with protests from students, mothers, veterans, and many others. One of the unpopular parts of the war was the draft, a system of mandatory military service among men called the Selective Service System. The draft started in the late 1950s and continued into the 1970s, pulling thousands of young men into Southeast Asia.

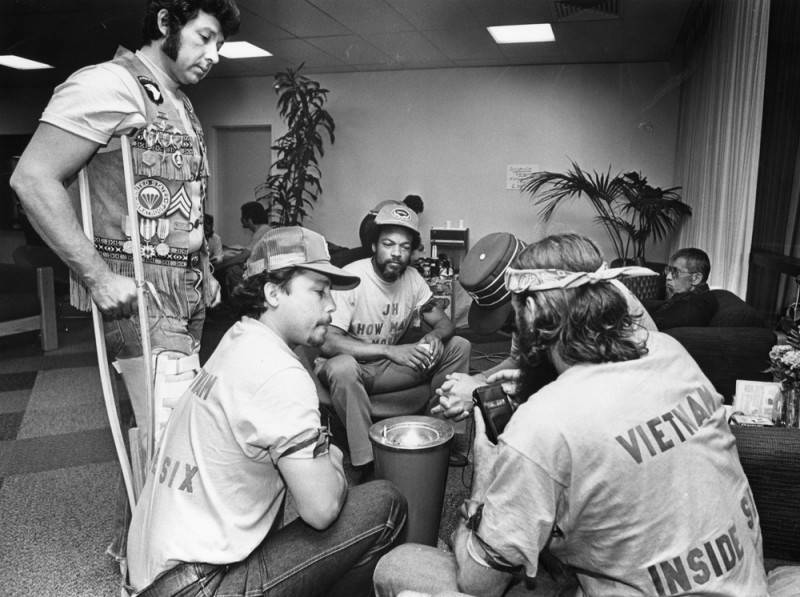

Once back home, Vietnam War veterans dealt with a hostile environment, the backlash from an extremely unpopular war. Many in the United States felt that the United States should not have been involved in this struggle and were thus unreceptive to welcoming our Vietnam War veterans home. Additionally, many veterans suffered chemical exposure, such as from Agent Orange, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a psychiatric condition from experience and exposure to traumatic events, from their war experience. The 1970s also marked the height of the closures of mental hospitals throughout the United States, limiting mental health resources to our veterans. As a result, some Vietnam War veterans, coming home to an indifferent society, became victims of homelessness through a lack of mental health care, addiction treatment, and job training.

After the withdrawal of American troops in 1975, the Third Indochina War began, a continuation of the armed conflict between Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and neighboring countries. During this time, Pol Pot led the Khmer Rouge in the deaths of millions of Cambodians; the indigenous Cham and other indigenous and minority communities were among those singled out for persecution. Until the Paris Peace Agreements in 1991 that ended the Cambodian and Vietnamese conflict, fighting continued between Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and neighboring countries.

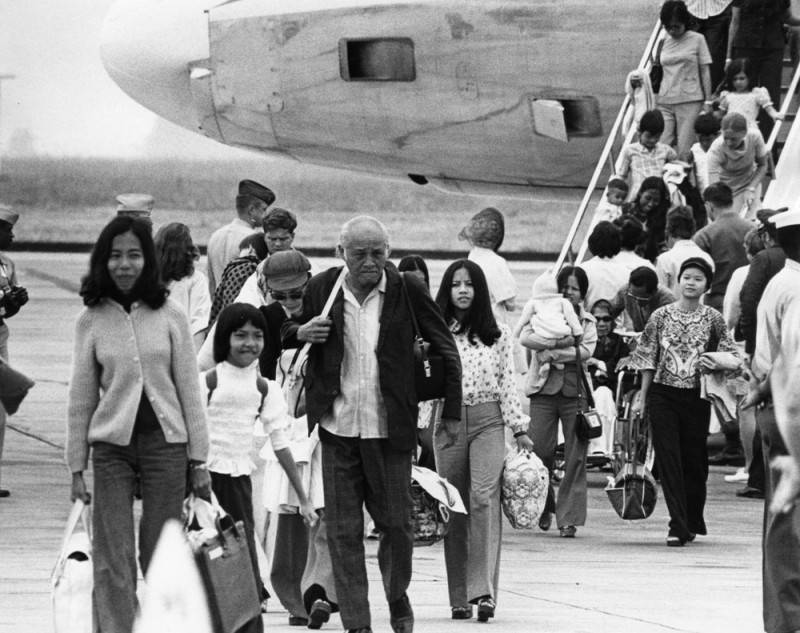

Immigration from this area into the United States has come in three major waves. The first influx came immediately at the war's end in 1975, with people being directly evacuated by planes. The second and largest influx was from 1975 to the 1980s, when approximately 2 million people, commonly known as "boat people," took a treacherous ocean voyage to Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and Hong Kong into refugee camps to apply for resettlement into Western countries. Starting in the mid-1980s and continuing to this day is the third wave of immigration, where fewer refugees are entering (due to refugee camps closures in the 1990s), more political prisoners and children of American servicemen coming in, and more family-based immigration.