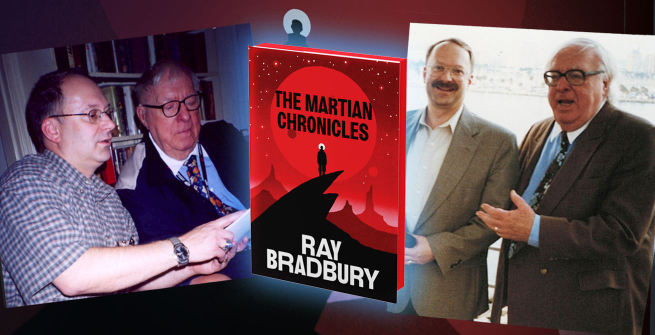

Jonathan R. Eller (B.S., United States Air Force Academy, 1973; B.A., University of Maryland, 1979; M.A. (1981), Ph.D. (1985), Indiana University) is a Chancellor's Professor Emeritus and co-founder of the Center for Ray Bradbury Studies at Indiana University's School of Liberal Arts. He directed the Bradbury Center for a decade prior to his retirement from Indiana University in 2021. He first met Ray Bradbury in the late 1980s, eventually developing a friendship and working relationship that lasted until Mr. Bradbury's passing in 2012. During the fall of 2013, Eller coordinated the gifting of Ray Bradbury's papers and correspondence, his entire office, working library, awards, and memorabilia to the Bradbury Center.

His books include the biographical trilogy Becoming Ray Bradbury, Ray Bradbury Unbound, and Bradbury Beyond Apollo, which was named a Choice Outstanding Academic Title. More recently, he has edited Remembrance: Selected Correspondence of Ray Bradbury. Four of Professor Eller's books on Bradbury have been LOCUS award finalists for best nonfiction title in the science fiction and fantasy field.

Professor Eller retired from twenty years as an Air Force officer in 1993; his military service included operational assignments with the Tactical Air Command, the Military Airlift Command, and the Pacific Air Forces before duty as an English professor at both the U.S. Air Force Academy (Colorado Springs) and the U.S. Naval Academy (Annapolis).

In celebration of the 75th anniversary of the publication of The Martian Chronicles, Bradbury's first novel, Professor Eller talked with Daryl Maxwell for the LAPL Blog about The Martian Chronicles, Bradbury, and the author's lasting influence on Speculative Fiction.

Do you remember your first encounter with Ray Bradbury's work?

I was ten years old when I read my first Ray Bradbury story. It was 1962, and I found a paperback copy of the 1953 story collection The Golden Apples of the Sun. I turned to the title story, which was the last story in the volume. The fantasy elements of this science fiction tale captured my imagination—a spaceship crew on a mission to scoop up nuclear fusion from the surface of the sun, with the crew protected from the sun's surface heat by the near absolute zero temperatures within the spaceship itself. There was no science here, just a fantastic wish fulfillment that would bring a scoop of nuclear fusion to Earth to provide energy far greater than the nuclear fission reactors of our time. It was a dream that never faded; years later, I would learn that The Golden Apples of the Sun also captured the imagination of many other young readers, some of whom would go on to become part of the space age.

When did you first meet Ray?

I met Ray Bradbury in the late 1980s, during the final years of my Air Force career, when I escorted him as he keynoted a four-day science fiction conference at the U.S. Air Force Academy. By 1993 I had retired from the Air Force and joined the faculty of Indiana University's School of Liberal Arts on the Indianapolis campus, where I continued to research Ray's very complicated process of re-writing many of his published stories and fusing some of them into book-length story cycles such as The Martian Chronicles, Dandelion Wine, Green Shadows, White Whale, and From the Dust Returned. By the late 1990s, I began to make regular visits to his homes in Los Angeles and Palm Springs. I also edited several small-press editions of Bradbury works with his good friend and bibliographer Donn Albright. Eventually, I wrote a three-volume biography of Ray's life and legacy.

How did you become involved with The Ray Bradbury Center?

The Bradbury Center was a natural outcome of my ongoing trips and research, and my occasional collaborations with my Indiana University colleague, the late Professor Bill Touponce, who had published two monographs on Bradbury's literary themes. In 2004, we co-authored Ray Bradbury: The Life of Fiction (LOCUS Award runner-up), the first university press-published study of Ray's career. In 2007, Bill and I co-founded the Bradbury Center in IU's School of Liberal Arts. Bill directed the Center until 2011, when he began to transition toward retirement. I served as director from 2011 until my retirement from Indiana University and the Bradbury Center in early 2021.

Can you tell us a bit about The Ray Bradbury Center?

Initially, the primary mission of the Center (known then as the Center for Ray Bradbury Studies) was to edit and publish The Collected Stories of Ray Bradbury, a multi-volume annotated edition of Ray's earliest stories published in the order in which he composed them. In a departure from the standard scholarly editing project, we published the seldom-seen earliest published versions of these stories rather than the more mature versions that he later gathered into his story collections and novelized story cycles. I also included backmatter lists of his later revisions so that readers could see the way that Ray would revise his published stories over time. During those early years, Bill served as editor for The New Ray Bradbury Review, a journal dedicated to publishing research articles by various scholars examining the various genres of literature and stage and screen writing that Bradbury explored during his career. The first two issues of the Review and the first volume of the Collected Stories were published before Bradbury's passing in June 2012.

Everything changed in 2013, when the Bradbury family gifted Ray's office and its contents and a lifetime of his awards and artifacts to the Center. At the same time, Donn Albright, Ray's close friend and long-time bibliographer, gifted the Center a large portion of the Bradbury papers and books that he had received as a bequest from Ray. Almost overnight, the mission of the Center broadened to include the curation, preservation, and accessioning of these treasures, a process that goes on today and will continue for many years to come.

Do you have a favorite of Ray's novels? A favorite short story? Something else?

The Martian Chronicles is my favorite Bradbury book, a novelized story cycle that asks us to care for this new world better than we have cared for our own home world.

"The Toynbee Convector" is a late science fiction story, but it is, perhaps, his best; I like it better than any other Bradbury tale because it reveals the core value of his very special brand of optimism. The story was sparked by his reading of the British historian Arnold Toynbee's concept of "challenge and response": when faced with an existential challenge, a culture must either believe it will prevail against all odds or turn away and die. No matter how dark things got, Bradbury never stopped believing in humanity.

A favorite "something else" would be the Nautilus submarine model that is in the Center's re-creation of Ray's home office. It is a carefully crafted model of Captain Nemo's undersea ship from Jules Verne's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, given to Ray by Disney Imagineer artist Tom Scherman. Ray would spend many years as a creative consultant for the Imagineers, and he wrote the narrative for Disney's Spaceship Earth experience at EPCOT.

2025 is the 75th anniversary of the publication of The Martian Chronicles. How is the Ray Bradbury Center celebrating this milestone?

I'm long retired from the Center, but my successor as director, Professor Jason Aukerman, tells me that the Center's annual "Festival 451Indy" will celebrate the 75th anniversary of The Martian Chronicles with a writing workshop, a multi-lingual read aloud event, and some related film events in Indianapolis. The Center's monthly Bradbury Story Club, an international virtual reading group, is also featuring The Martian Chronicles.

What records, documents, manuscripts, or artifacts does The Ray Bradbury Center have in its collections that are related to The Martian Chronicles?

The breakthrough success of The Martian Chronicles in 1950 made Bradbury a natural choice to speak for the achievements of the space age. The Center displays many of his awards for his service to NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, including a "Mars" flag that went to the International Space Station aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery in 2006. He also received a three-dimensional plaque of the Valles Marineris, almost four times larger than Earth's Grand Canyon and five miles deep. A very deep chasm within the Valles Marineris is widely (but unofficially) known as "The Bradbury Abyss."

The Center also exhibits a Mars globe based on the November and December 1971 photographs of Mars taken by Mariner 9, the first mission to achieve a successful Mars orbit. Decades later, the Phoenix lander arrived in the far northern latitudes of Mars in 2008 with a special DVD containing a library of literary works about the planet Mars. It features a digital copy of The Martian Chronicles, a cover illustration by Michael Whelan from later editions of the novel in America, and a 1950s Spanish language introduction by the Argentine author. Jorge Luis Borges. The durable DVD was securely fastened to the deck of Phoenix prior to launch; Bradbury's copy of that DVD is displayed in the Bradbury Center.

What have you, the Ray Bradbury Center staff, or researchers discovered or uncovered about The Martian Chronicles from research done with the collections?

The Center's collections shed much light on Bradbury's desire to revise many of his stories as he brought them into his own story collections, and his equally intensive process of forming novelized story cycles out of groupings of related stories. Nowhere is this process more apparent than in the six variant published forms of The Martian Chronicles.

But there is also typescript evidence of changes to the individual Martian Chronicles stories well before they were ever published at all. "Ylla," the opening story that establishes Bradbury's exotic and ancient Martian culture, was revised by Bradbury as it slowly made its way through eighteen different submissions to various pulp and major market magazines. Comparisons of the published version with the earliest surviving typescripts revealed that Bradbury gradually made Martian artifacts more alien, replacing household dusters with magnetic dust attractors, cooking stoves with bubbling lava pits, and guns with living particle weapons. These changes add to the eerie and chilling sense of otherness that confronts Earth's first ill-fated contact expeditions.

Having known and worked with Ray, is there something you know about him that his readers might not know, but should?

As a teenager and young adult, Bradbury discovered that he loved acting even more than he loved writing itself. Ad-libbing lines in comedy farces and high school reviews was one thing, but when he was cast in the romantic lead for an amateur production of Money for Candy in 1940, he realized that he had no ability to memorize lines. He was saved when the director, Hollywood actor Hugh Beaumont, was called away to another commitment, and Money for Candy never opened. He would eventually produce stage adaptations of his own stories with his own acting companies throughout the Los Angeles area, but that was still decades away in the future.

Do you have a favorite manuscript, artifact, or other part of the Ray Bradbury Center collection?

The Bradbury Center curates several artifacts that have been in outer space, and one of these artifacts is a favorite of mine—it's a packet of seeds which were part of the SEEDS Project prepared by scientists from the Department of Agriculture's Agriculture Research Service. The Bradbury Center's tour notes reveal why this small artifact from Ray Bradbury's home office is so special: "This packet orbited the Earth on the Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF) Satellite, which was retrieved after six years by NASA. The packet of seeds was launched on the Space Shuttle Challenger on April 6, 1984, and returned to Earth on Space Shuttle Columbia in January 1990. Both shuttles were lost with astronauts on board during later missions, a very sobering reminder of the sacrifices that have been made to advance the exploration of outer space."

In your opinion, what is it about The Martian Chronicles that keeps drawing readers, old and new, to it?

There is nothing scientific or even plausible about The Martian Chronicles, but it remains relevant 75 years after its first publication. The tales that he pulled together and bridged to form a novelized cycle of stories represent a myth for modern times, an alternative to Modernism that offers a new kind of frontier—no longer a migration across dangerous oceans, but a far more dangerous migration to another world.

The Martian Chronicles is also a cautionary tale, a reminder of how advanced civilizations had already displaced native peoples and exploited the resources of their own home world. The human propensity for exploitation and conspicuous consumption will migrate along with the pioneering settlers of Mars. In "How I Wrote My Book," written in October 1950, Bradbury described how people from all walks of life would go to Mars, "thinking they will find a planet like a seer's crystal, in which to read a magnificent future. What they'll find, instead, is the somewhat shopworn image of themselves. Mars is a mirror, not a crystal."

Earth's wars bring the colonists home from Mars, but a few new settlers will return, bringing hope for a second chance and a renewed dream of eventually heading out to the stars. The Martian Chronicles is every bit as cautionary as Fahrenheit 451, and every bit as enduring.

Similar question regarding Ray's work overall. What is it about Ray's work that continues to fascinate and challenge contemporary readers?

Bradbury's science fiction concentrated on exploring what it means to be human. Science and technology usually remain in the background, forming an armature upon which he could fashion highly emotional tales about the space-faring challenges of isolation, loneliness, and fears of unknown (and perhaps unknowable) things out in the cosmos. Yet Bradbury was nonetheless a major force in bringing science fiction into the literary mainstream. He was also a master of the cautionary tale, a preventer rather than a predictor of such futures as Fahrenheit 451. He did not mistrust science and technology, but he was always wary of those who controlled it. Science is only dangerous when those who create it and those who control it forget the vital importance of human values.

Above all, Bradbury was a master of fantasy and magical realism, ranging from stories of rebirth and renewal and childhood joy to off-trail weird tales that often explored the fundamental relationship between life and death. His 1962 novel Something Wicked This Way Comes offers a timeless exploration of good and evil that still resonates today. Almost all his prodigious output remains in print, and generations of readers have passed his legacy on to their children and grandchildren. His metaphor-rich, lyrical prose contains twist endings and unusual protagonists who break all the genre rules across several fields of fiction. Everybody knows at least one Ray Bradbury story—he remains one of the best-known writers of our time.

We lost Ray Bradbury in 2012. If you had the chance to ask Ray something, what would it be?

Ray Bradbury's childhood reading passions included the Martian novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs, whose protagonist, John Carter of Earth, developed the ability to travel to his adapted home world and the Martian princess he had married. In his 2003 introduction to the Modern Library edition of A Princess of Mars, Ray recalled how "at the age of nine, ten, and eleven, I stood on the lawns of summer, raised my hands, and cried for Mars, like John Carter, to take me home." If I had the chance to ask him any question today, more than a dozen years after his passing, I would ask if he finally made it to the planet he had called "home" so many years ago.

If you could tell him something, what would it be?

I would let him know that NASA's Curiosity rover landed on Mars just two months after his passing, touching down on a spot that the mission team named Bradbury Landing; I would tell him that Curiosity is still exploring Gale Crater more than a dozen years later, where it has found evidence of water on Mars that may have lasted on the surface for a million years.

What's currently on your nightstand?

A book I've just finished reading: Red Side Story, by the British novelist Jasper Fforde (yes, "Fforde" with two "ff" s). It's a sequel to Fforde's Shades of Grey. Together they describe a dystopic future which (like Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451) comes to a redemptive ending.

Can you name your top five favorite or most influential authors?

I have always been drawn to the drama of George Bernard Shaw and Eugene O’Neill, the science fiction trilogy of C. S. Lewis, the anthropological science fiction of Chad Oliver, and the poetry of T. S. Eliot.

What was your favorite book when you were a child?

The Martian science fiction romances of Edgar Rice Burroughs were my collective favorites at the ages of ten to twelve. Every week, I would escape from my parents in the grocery store and hide in the book section, where I could find the new Ballantine paperback editions of the Mars novels with their eye-catching cover paintings. Like Bradbury, I was fascinated by the techno-barbarian civilizations boasting warriors armed with radium pistols and swords, moving through the red skies of Mars in battleships of the air. Every Martian city-state had a back story that reached far into the past to a time when Mars had seas. The action was sometimes formulaic, but the tapestry was rich.

Was there a book you felt you needed to hide from your parents?

My mother was a great reader, and I never felt the need to hide a book at home. However, I often read novels from the school library late into the night and hid this habit by reading by flashlight under the covers of my bed. Apparently, I was in good company; I have read that Margaret Atwood and other authors also read by flashlight when they were young and supposed to be asleep.

Is there a book you've faked reading?

My gateway into many classics of American, British, and Continental fiction opened through the pages of the Classics Illustrated graphic adaptations of the 1950s and early 1960s. When I later read and sometimes taught the actual novels, the carefully composed art panels from the pages of Classics Illustrated always came to mind. I was fortunate and never fell victim to the pressed-for-time professor's lament: "Have I read it? I haven't even taught it yet."

Can you name a book you've bought for the cover?

From time to time, you will still see variations of Joseph Mugnaini's original "burning man" cover concept on various editions of Fahrenheit 451. The haunting cover figure, a tall man armored in newsprint, was a blend of Mugnaini's earlier illustration of Don Quixote in sixteenth-century armor and a newsprint-clad illustration of the ancient Greek philosopher Diogenes. Ray had seen both images in Mugnaini's studio, and felt that a newsprint-armored figure, licked by flames, would be perfect for Fahrenheit. The Ballantine 1953 first edition hardbound dust jacket soon became very pricey, but the simultaneous Ballantine mass-market paperback wrapper with a full-color painting of the burning man was not so hard to find; copies of the paperback in fine condition would turn up in used book stores for decades, and I was able to buy one that I still have today.

Is there a book that changed your life?

In grade school, the first long novel I ever read in its entirety was A Tale of Two Cities, by Charles Dickens. Each student in our sixth-grade class was instructed to choose a novel to read individually, and I was a bit nervous about selecting 469 pages of Dickens. To my surprise, I soon came to see the characters, understand their motivations, and appreciate their individual destinies. I looked around the library as I returned the book, and I knew that a whole new world of reading was now open before me.

Can you name a book for which you are an evangelist (and you think everyone should read)?

I believe that Darkness at Noon (1940), by Arthur Koestler, is a book that everyone should read if they want to understand the internal workings of a mid-twentieth-century totalitarian state. Reading the novel was a major influence on Bradbury as he wrote "The Fireman" in 1950; seeing the 1951 Pulitzer Prize-winning Broadway stage adaptation had a further impact on Bradbury, providing the final push behind his expansion of "The Fireman" into Fahrenheit 451.

Is there a book you would most want to read again for the first time?

The Martian, by Andy Weir. Bradbury's vision of Mars dominated our dreams of the Red Planet for forty years; Kim Stanley Robinson's Mars trilogy of the 1990s amplified the challenges of bringing life back to Mars. And Andy Weir's The Martian offers a solitary survivor's story as he "sciences" his way through every problem he faces, prompting readers to contemplate how we might react to the loneliness and isolation and the terrors of an alien environment that seems so cold and hostile to life as we know it. And what Bradbury imagined about alien contact is further echoed in Weir's subsequent interstellar novel Operation Hail Mary, which demonstrates an unconquerable will to live and sacrifice for others, no matter how different and unapproachable they may seem to be.

What is the last piece of art (music, movies, TV, more traditional art forms) that you've experienced or that has impacted you?

Gustav Holst, The Planets, Op. 32 (orchestral suite) remains my most impactful musical experience.

What is your idea of THE perfect day (where you could go anywhere/meet with anyone)?

I would take my wife up to our favorite places along the Canadian shore of Lake Huron, where we could see the great Niagara Escarpment continue north over the horizon and drop into the Georgian Bay. Such immensities of geography dwarf the human scale of things—it's a great place to read a book.

What is the question that you're always hoping you'll be asked, but never have been?

What will we become when we reach the stars?

What is your answer?

Ray Bradbury will tell you.