For someone who only spent about 25 years in Los Angeles, Edwin Cawston made a lasting impression on the cultural history of our great city and he did so through, of all things, a farm. Dubbed by the New York Journal as “one of the strangest sights in America”, the farm was anything but ordinary. Its commodity was not fruit, vegetables or even livestock—it was feathers that were derived from a nine-foot-tall bird: the ostrich. In its heyday, Edwin Cawston’s Ostrich Farm was recognized for quality products that were shipped around the world but it would be a secondary consideration that ultimately played an important role in making the business a success: tourism. Because of tourism, Edwin Cawston’s farm evolved into one of nineteenth-century Los Angeles’ biggest attractions, a source of civic pride and one of the most romanticized sites in L.A. history. Although long gone, the farm has never really been forgotten and its disappearance has only perpetuated a romantic mythology about it. In fact, discourse about this lost tourist mecca focuses more on the farm rather than its creator or his role in making the farm a success. Understanding that, let’s look back at Edwin Cawston’s Ostrich Farm, its creation and its success through a narrative that puts Edwin Cawston front and center.

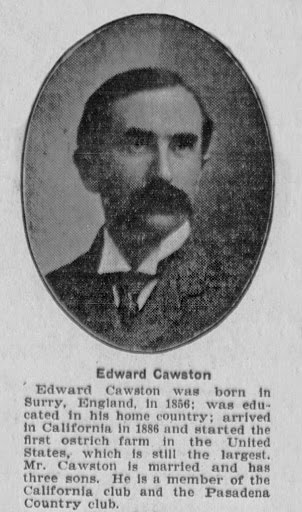

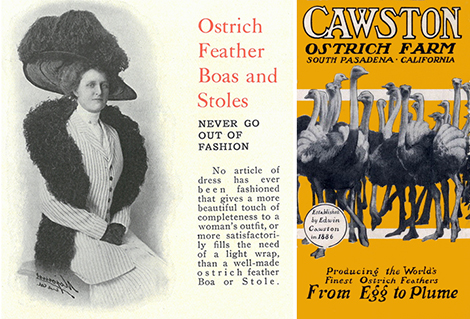

Edwin Cawston was born to Sam and Elizabeth Cawston in 1866 near London. Sam Cawston was a stockbroker and his success afforded his son the opportunity to explore the world at his own leisure. Cawston appears to have enjoyed this privilege but not because he lacked direction; in fact, he seemed to be intent on making his own way in the world and found his purpose while on an excursion to New York. Based on his own accounts, Cawston first visited the United States around 1884. A story published in the Pacific Rural Press relayed that it was while en route from Niagara Falls to Buffalo that Cawston read a magazine article on the British ostrich feather industry in South Africa. The use of feathers as fashion accessories had exploded in the Victorian era and ostrich plumes had become the “must have” accoutrements of the day with demand exceeding supply. The magazine told of the great profits that could be made from ostrich plumes with (relatively) minimal effort and this caught Cawston’s attention. Cawston, however, would soon learn the hard way that South Africa had a monopoly on the industry that would be tough to break.

In 1885 Cawston travelled to British-controlled South Africa with the intent to survey the operating farms, learn the nuances of ostrich farming, and purchase some birds for himself. When he arrived in Cape Colony, Cawston learned that a steep tax had been levied on exporting ostriches that was meant to reinforce the South African monopoly. Cawston wrote, “this industry is thought so valuable to Cape Colony that the government has levied a duty of $500 on every ostrich exported.” The law would require anyone taking an ostrich out of Cape Colony to be taxed approximately $500 per bird and $125 per egg. In the Natal province of South Africa, however, the tariff was still being debated in Parliament and had not yet been enacted. “In order to avoid this heavy tax” Cawston later recalled, “which would have greatly handicapped the new industry in California, we proceeded by steamer to Natal, on the east coast, much farther north. We reached Durban, the chief port, and from there made many runs to the interior, visiting different parts of the colony in search of birds. We found few ostriches were raised there, and that they were held in slight esteem by the natives until it became known that someone was desirous of purchasing, and then there was a rapid boom in the market.” Cawston, fearful that the longer he stayed in South Africa the more likely the tax would be enacted, left Durban via ship with fifty two birds headed for America. Without the convenience of the Panama Canal to make a direct voyage to Los Angeles, the ship arrived in Galveston, Texas after sixty eight days at sea. Eight of the birds had died on the voyage with three succumbing to injuries sustained during rough weather. One plucky bird named “Murphy” escaped his pen and decided to gorge on a stash of potatoes reportedly eating himself to death; two more birds died in Galveston. From Galveston, Cawston arranged to rent a railroad car to move the birds out to Los Angeles.

Los Angeles

In June 1886, at the ripe old age of twenty, Cawston and forty two ostriches arrived in the Los Angeles area. In an article Cawston wrote for the English magazine, Country Life Illustrated, he explained that he had managed to make it out to Southern California during his 1884 trip to the United States. Based on that visit, Cawston was able to conclude that it was possible to raise the birds in Southern California because, as the Herald reported, there were at least two farms (in what is now northern Orange County) that had been operating since late 1882 and/or early 1883. Cawston purchased 20 acres in Norwalk, not too far from where the other ostrich farms and where there was plenty of open land. Nearly half of the Norwalk property was devoted to raising crops like alfalfa, sugar beets, corn and fruit that served as a food source for the birds. He wrote that the ostriches adapted quickly to their new surroundings and elicited curiosity from spectators who weren’t sure what they were looking at: “...some ludicrous things happened, at least we thought them funny. One man, to this day, is minus his straw hat, which was promptly whipped off his head and devoured as a dainty morsel by a couple of these gigantic birds.” The Norwalk location, however, was never intended to be a tourist destination, it was a working farm: “At my farm here at Norwalk, these [tourism draws] form quite a secondary consideration, the production of feathers and chicks being my chief aim.” The novelty of raising these birds so far outside of their natural habitat was of interest for the general public and the Nowalk location was surprisingly well covered in the press. Stories about the Norwalk farm were published in magazines like Harper’s Weekly and newspapers like the Pacific Rural Press. Significantly less coverage, however, was devoted to Cawston’s first (public) commercial venture.

Washington Gardens

In February 1887, Cawston and a partner, Charles Fox, established what the Times described as an “exhibition ostrich farm” at the Washington Gardens amusement park on Main Street and Washington Blvd. The business, the Washington Gardens Ostrich Farm and Zoological Gardens, was designed by M.F. Brown, the man responsible for the grounds for the New Orleans World Fair a few years earlier. The Times reported that the gardens were “tastefully laid out” and a mural created for the World’s Fair was imported to Washington Gardens at great cost for the new venture. On February 2nd, twenty-one ostriches were brought to Washington Gardens with a caretaker, E.P. Hoyle. In March, a fire consumed the main pavilion where, among other things, the zoo workers were housed. The Times explained that the building had been “leased to Messrs. Cawston & Fox” but no one, including the animals, was harmed in the fire. The pavilion, however, was destroyed. David Waldron, the owner of the park rebuilt the pavilion and added a Thursday and Sunday afternoon promenade concert to the lineup of activities but it wouldn’t matter as Cawston didn’t stay at Washington Gardens much longer.

Little has surfaced on Cawston’s time at Washington Gardens likely because it was such a short run but, in his reporting on the farm, writer E.H. Rydall did contribute the following which made it clear that the venture had limited success: “He got to Los Angeles and opened a menagerie of his ostriches and a lot of wild cats, mountain lions, skunks, opossums and other carnivora. His father kept sending him money, for he thought he needed it and he did. The tourists who visit California did not go in crowds to see his show; they would not buy his ostrich feathers and, sad to relate, his ostriches began to die. So he was wise; he closed the menagerie, sold his smelling carnivora to the highest bidder for cash…” Early in 1888, Cawston and his birds took the opportunity to leave Washington Gardens for good. A March 1888 Herald story reported that Cawston had “transferred” his birds back to Norwalk from Washington Gardens and by May, he was being referred to as “the former proprietor of the Washington Gardens Ostrich Farm.” While the Washington Gardens venture proved to be a bust, Cawston did learn that his birds were loved by visitors and they would spend good money to see them up close.

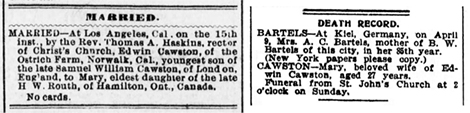

The Routh Sisters

In April of 1889, Cawston married Mary Routh, a Canadian transplant who arrived in Los Angeles two years prior with her sister Fannie. For whatever reason, Mary has been absent from much of the documentation on Edwin Cawston and it is difficult to find a whole lot other than the pair were wed and she gave birth to a son, Arthur, in 1890. In early 1894, Mary checked in to the Abbotsford Inn on the corner of Eighth and Hope Street in Downtown Los Angeles for reasons that are unclear but probably related to visiting a doctor. Mary died while at the Abbotsford Inn on April 28, 1894: Her death certificate listed the cause as phthisis pulmonalis or, as it is more commonly known, tuberculosis. Pasadena was a haven for tuberculosis patients in the nineteenth century and Mary probably came to the area to take “the California cure.” Her symptoms were likely in remission during her courtship with Cawston but re-emerged and ultimately killed her. Funeral services for Mary were held at St. John’s Church and she was buried at Mountain View Cemetery in Altadena. Her epitaph reads “Mary, beloved wife of Edwin Cawston. Aged 27 years” (although a century of weathering makes the inscription look like 22 instead of 27). Lyrics from a Christian hymn, “Jesus, lover of my soul, Let me to thy bosom fly” appear at the bottom of her tombstone but have become too weathered to fully discern.

Like most men of the era, Edwin was probably ill-prepared to raise a child on his own and chose to remarry to ease his paternal responsibilities. He chose Frances “Fannie” Routh, Mary’s older sister, as his bride. Marrying his wife’s sister may seem strange by today’s standards but, at the time, it wasn’t uncommon. Given the small population of Los Angeles County at the time and Cawston’s focus on his fledgling business, it would have been difficult to find a suitable partner that he could also trust to raise his child. Edwin and Fannie married January 1, 1895, a new year and a new start. Fannie gave birth the following year to their son Edward (Edwin Jr.) and two years later, another son, George, was born. Like her sister, Fannie also passed away prematurely in November of 1899. Although her cause of death could not be verified, it stands to reason that it may have been related to tuberculosis given the highly contagious disease had killed her sister. Fannie was buried next to Mary at Mountain View Cemetery in 1899. The U.S. census, taken the following year, lists Edwin Cawston as a widower with three young sons living at a South Pasadena address.

South Pasadena

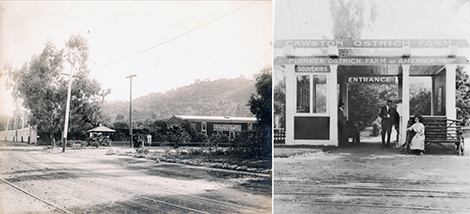

The Washington Gardens debacle no doubt soured Cawston on another zoo-like enterprise so he had gone back to basics and was now committed strictly to his birds. The Norwalk farm was intended to function solely as a place to raise chicks, harvest feathers, and experiment with breeding a heartier stock of birds. It wasn’t meant to host visitors, but they seemed to keep showing up. For example, one story reported that seven companies of cadets from the Whittier State School celebrated Washington’s birthday in 1894 by visiting the Norwalk farm. At some point, Cawston got the idea to combine the day to day operations of Norwalk with the showmanship and accessibility of Washington Gardens. It would be an enterprise that would focus on the production and supply of plumes to the market but in an environment that welcomed visitors. Unlike Washington Gardens, however, Cawston would have complete control over the operations and it wouldn’t impact the primary focus of his business. On May 25, 1896, the Herald reported that Cawston had been looking at the area “somewhere along the line of the electric road between Pasadena and Los Angeles” to create his new “tourist friendly” ostrich farm. That location was South Pasadena.

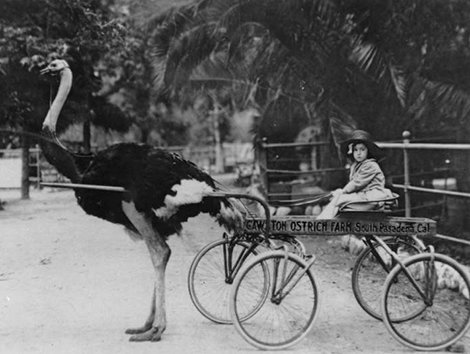

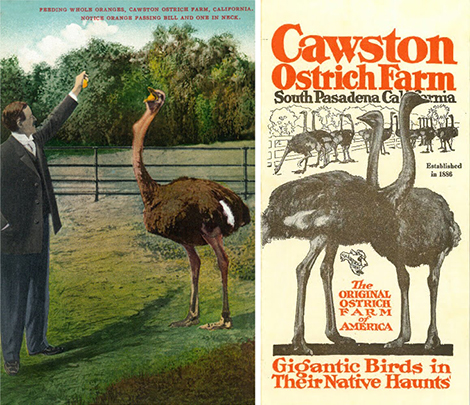

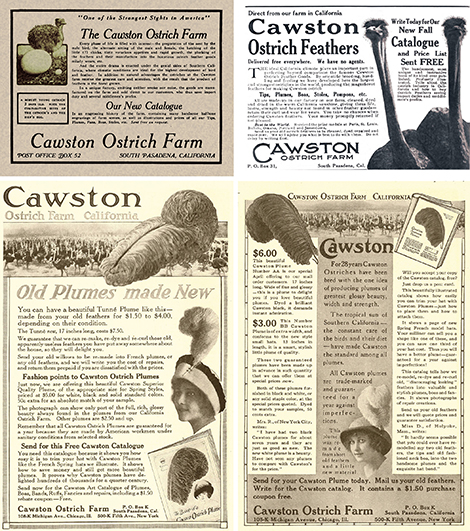

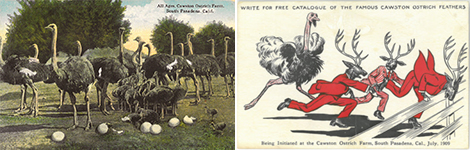

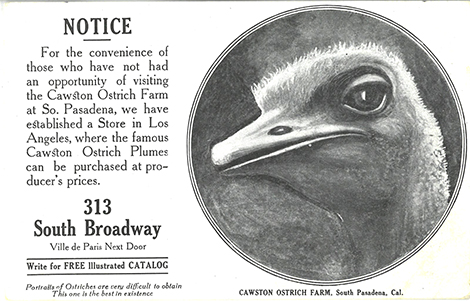

The South Pasadena farm would allow Cawston to conduct the business he had set out to do when he arrived in 1886, but it would also allow the public to see these birds that had captured their imagination. The grounds at the South Pasadena location were deliberately cultivated to be tourist friendly and included gardens, a “Japanese” tea room, a retail store, a dye and curling factory, and an ostrich pen where tourists could view the birds, feed them, or take photos of them. Stories praising the beauty of the farm and its gardens began to appear in newspapers with the Herald gushing “The farm is rapidly becoming one of the most picturesque spots in the neighborhood of Los Angeles, the grounds having been laid out in the most attractive manner, quite in keeping with the beautiful natural surroundings.” Visitors were photographed being pulled in a cart by an ostrich, sitting on a taxidermied ostrich that, if alive, would have otherwise bucked the rider off or, the adventurous could attempt to ride a live bird. Cawston also ensured that his business would be a hub of tourist visitor activity by making it a stop on the Pacific Electric line. In December of 1896, the Herald reported that “the proprietors of this interesting place have arranged with the electric railway company that “stop over” tickets would be granted to all travellers to visit the ostrich farm on their way to or from Pasadena to Los Angeles.” The farm became renowned for its technological advancements when Cawston incorporated Aubrey Eneas’ massive cone-shaped reflector into the farm’s operations. Eneas’ device looked like a giant satellite dish but was essentially an early incarnation of solar panels that would transform sunlight into energy and power the farm’s water pumps. The farm, no doubt, was beginning to surpass the expectations that Cawston had imagined for his business. Tourism not only made Cawston a lot of money, but established his reputation within municipal circles.

Boosterism, Civic Pride and Influence

Despite being just outside the City of Los Angeles, the Cawston farm was a focal point in the city’s boosterism campaigns of late nineteenth and early twentieth century. On any given day, the Times featured the “South Pasadena Ostrich Farm” as the leading “Amusement and Entertainments” feature. The farm emerged as a centerpiece in Chamber of Commerce publications and similar booster material. In 1902, Cawston was reported to have hosted a visit by both officials from the Chamber of Commerce and the Merchants and Manufacturers Association of Los Angeles in which both groups were invited to see the farm and view a “plucking” of the ostriches. A year later, the Chamber of Commerce presented Cawston with “a colored photograph nine feet in length, giving a unique and lifelike scene among ostriches.” Cawston was also invited to become a member of the prestigious California Club and the Pasadena Country Club. The farm was also documented exhaustively in postcards of the era, sent out across the country enticing prospective visitors to see one of the great wonders of the Los Angeles area. Most important of all, the farm was advertised in newspapers and national magazines such as Harpers Weekly, Colliers, The Saturday Evening Post, Sunset and the Ladies Home Journal. In 1904, the Times reported that Cawston spent nearly $61,000 in advertisements that “are placed in papers in every civilized country in the world.” Edwin Cawston effectively brought both national and worldwide attention to the area at the exact same time Los Angeles was fighting for any kind of prominence as a metropolitan center.

For South Pasadena, the farm became pivotal in cultivating the city’s identity because it put the city on the map for the public. Indeed, when people from around the world ordered ostrich feathers via the post office they were sending money to and receiving goods from South Pasadena. By 1901, the Ostrich Farm was an established tourist destination that got a shot in the arm from the tourists staying at the rebuilt Raymond Hotel. The Raymond re-opened December 1901 after a devastating fire had consumed the original structure six years prior. The hotel site, at the top of Raymond Hill, provided an inviting view of the farm and no doubt enticed curiosity struck guests to stop by for a visit. The Herald reported on the development of South Pasadena in July, 1903, stating the city was growing rapidly and could count four churches of different faiths and a public library among its civic assets. Of course, the paper saved the best for last: “The big ostrich farm of Edwin Cawston is the best known feature of South Pasadena, and has done more to advertise the place than any one form or attraction.”

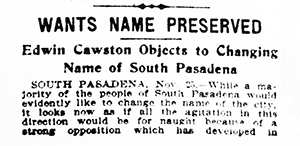

Edwin Cawston was fully aware of the role that his farm played in the development of South Pasadena and in November, 1903 he asserted that clout. Newspapers reported that there had been an ongoing effort to change the name of the city in order to distance itself with its much larger neighbor to the north, Pasadena. Cawston was opposed to this change and it was reported that he wrote a letter to city officials threatening to relocate his farm if officials changed the name of the city. He argued that people all over the United States and Europe knew that his farm was located in South Pasadena and, therefore, changing the name might adversely impact his business. Officials capitulated and the city retains its name to this day, ultimately because of Edwin Cawston.

A New Beginning

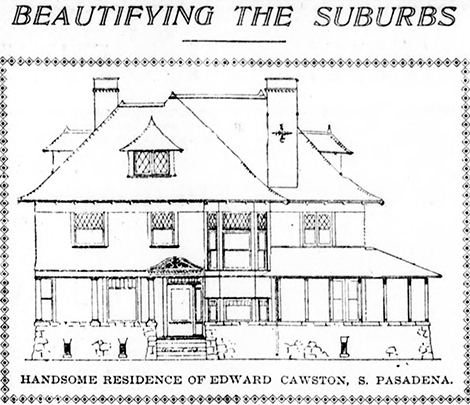

With his business in solid standing, he had time to find romance with the woman who would be with him until the end of his life: Edith Doran. The pair were married in a low-key ceremony held at the bride’s mother’s home on Olive Street at the end of April, 1901. Details of the ceremony were featured in the society section of the Times and explained the pair would honeymoon in Europe, allowing Cawston could introduce Edith to his family in England. They returned to Los Angeles in August and the Herald reported that Cawston was in the process of building a home for his new bride, for an estimated at $5,000 (approximately $140,000 today). The couple had two children together, Marjorie in 1907 and John in 1910.

For the Birds

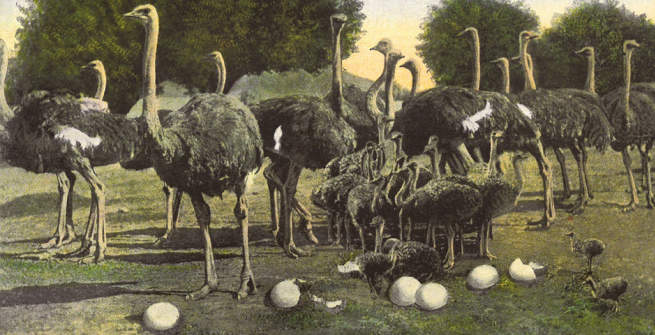

Cawston’s ostriches delighted the public to no end, ensuring a steady stream of visitors to the farm, and by 1900 the ostrich population had grown substantially. The original birds from South Africa had died out with the last passing around 1899, but they were replaced by a new generation that were particularly hearty. An article for the British periodical, The Harmsworth Magazine explained that one pair of birds had 37 chicks in a single year while birds in the wild rarely had more than a dozen. The Pacific Rural Press reported that Cawston was now looking for a farm that would be devoted exclusively to growing produce to feed the 500 birds at Norwalk and the 200 at the South Pasadena location.

The birds enchanted Angelenos and would be featured periodically in silly human interest stories throughout local newspapers. One such story touted the group “wedding” of four sets of birds and locals were encouraged to suggest names for the “newlywed” couples. Most of the birds on the farm were given the names of politicians or royalty with the largest bird at South Pasadena named in honor of President William McKinley. Other birds were named after famous historical figures like Grover Cleveland, Beau Brummell, George & Martha Washington, Antony & Cleopatra, etc.

Edwin Cawston was very conscientious about his farm’s image and made it a point to express that his birds were being properly cared for. As organizations meant to protect animals from cruelty began to take shape in the United States in the late nineteenth century, Cawston took notice. An 1896 story in the Times reported that Cawston had expressed that, despite regular use of the term ‘plucking’, his methods of obtaining feathers from the birds was not cruel because the feathers were clipped with shears and not actually ripped from the animals. The use of the term plucking had become a blanket term when dealing with feather removal from any kind of bird but was ultimately misleading in the case of Cawston’s farm. He clarified, “...the term plucking is a misnomer...to pluck them out would injure the birds and be very painful, and the ostrich farmer is very careful of his valuable stock...if the socket in which each feather grows is injured in any way another feather will not grow in that socket; from this one can understand how carefully the harvesting of feathers has to be attended to.”

An 1899 article that Cawston himself penned in the Pacific Rural Press also made it a point to state that, unlike other bird feathers, none of his birds were slaughtered to obtain their wears and he regularly drove this point home. He even made a plea to female consumers, appealing to their sense of humanity to choose his ostrich feathers instead of other types of feathers for their hats and accessories: “I am sure if ladies stopped to think a moment they would do more than they are doing now to discourage the indiscriminate and cruel slaughter of hundreds of thousands of brightly plumaged birds at all seasons of the year, irrespective of nesting time or anything else. Undoubtedly the ostrich was made to furnish feathers just as the sheep furnishes wool; and putting personal pecuniary interests aside, I think all ladies should encourage and support by practical means the efforts of those kind-hearted ladies who are doing all in their power to discourage the senseless fashion that entails so much wanton waste and cruel destruction of bright bird life.” Cawston would reiterate his belief that clipping feathers was no different from shearing a sheep for its wool and, in his catalogs, he included a disclaimer that feathers were clipped with shears and not actually “plucked.”

Cawston was also quick to address any misconceptions, misinformation, and rumors that were circulated about ostriches. He would often write to the Times to clear up any problematic reporting they may have done on the birds and would talk directly to visitors to the farm to educate them about ostriches. He explained their courting rituals, how they managed and cared for their eggs, their temperament and what their daily activities were. He was particularly quick to address ill-informed ideas about their diet writing, “the ostrich is a most voracious bird, and will consume a great quantity of food.” He insisted that they didn’t exist on tin cans, rusty nails, and old tires as rumored but would occasionally snatch something that caught their eye and consume it. “On rare occasions,” He said, “I have seen one swallow a lighted cigar, a gimlet, a lady’s purse, a society paper rolled up for mailing and an old shoe.” Promotional literature for the farm insisted that that ladies should refrain from wearing shiny objects, and gentlemen should not smoke cigars or hold anything too conspicuous near the birds.

The Beginning of the End

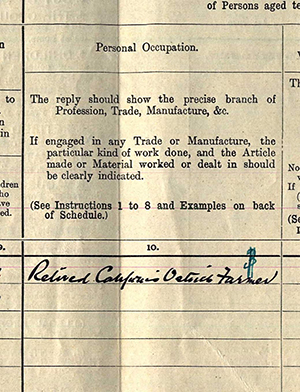

In November 1903 Cawston began filling out paperwork to become a naturalized citizen of the United States. However, he never completed the process, indicating some apprehension about becoming a permanent resident. Indeed, since his honeymoon, he began returning to England with some regularity and there is a distinct fade from Los Angeles area civic life and farm operations that becomes more pronounced from 1905 to about 1910. In November 1905, the Herald ran a report indicating that Cawston was looking to sell his farms (South Pasadena and Norwalk) to an investment company for $250,000 but no further reports ran. In March 1909, he appears to have sold the Norwalk farm and moved the nearly 1,000 birds who lived on the property to a larger space in San Jacinto. It was reported the San Jacinto property would now serve as the ‘breeding farm’ while the South Pasadena location would remain the “show farm.” On October 25, 1911, following another visit to England, Cawston boarded the S.S. Oceana at Southampton to return to the United States. His final destination in the passenger manifest records indicates he was headed to Los Angeles and his profession is listed as “none,” a sign of what was to come. In November 1911, reports ran that Cawston sold the farm in South Pasadena and San Jacinto for $1,250,000 (approximately $32 Million today) to a syndicate of Los Angeles bankers. By December he had returned to England. Cawston, Edith, John, and Marjorie appear in 1911 English census records as residents of England with Cawston recording his profession as “Retired California Ostrich Farmer.”

Cawston would not live to see the demise of his farm. On June 29, 1920, the Times reported that Cawston died in England from heart disease at the age of 54; He was buried in England in the first week of July. Though the farm continued to operate until 1935, it was a pale ghost of itself without the verve of the man who gave birth to it. As the jazz age encroached, styles began to change turning fashion accessories like feathers into a relic but it was really the Great Depression that effectively caused its demise. Excesses in the form of ostrich feathers just weren’t within the grasp of people who were struggling just to survive. It was reported that, in 1949, the 22 room house in South Pasadena where Cawston lived was torn down so the lumber could be used for a veteran’s home.

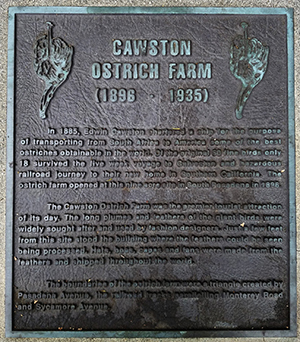

A plaque now stands on the site where the farm once stood.